Abstract

Of the 630 members of a specialized set of committees responsible for drafting the federal rules for civil and criminal litigation, 591 of them have been white. That is 94 percent of the committee membership. Of that same group, 513—or 81 percent—have been white men. Decisionmaking bodies do better work when their members are diverse; these rulemaking committees are no exception. The Federal Rules of Practice and Procedure are not mere technical instructions, nor are they created by a neutral set of experts. To the contrary, the Rules embody normative judgments about what values trump others, and the rulemakers—while experts—are not disinterested actors. This Essay examines racial and gender diversity across six different committees through original research. The data tell a textured story of homogeneity, diversity, and power. Critically, the respective committees’ demographic compositions differ both historically and now. But there is one significant similarity across all committees: The Chief Justice can and should appoint a more diverse set of individuals to these committees, and the rulemaking committee members, the judiciary, and the bar should demand it.

Introduction

Rules matter because they determine how the game is played. This is especially true in civil and criminal litigation. Will evidence be admitted?[1] Can you access discovery from your opponent?[2] Can you appeal?[3] Can you file a bankruptcy petition?[4] Can you be held in criminal contempt?[5] In the federal system, all of these questions are answered first by the Federal Rules of Practice and Procedure.[6]

In considering diversity’s impact on how these questions play out, the focus tends to be on the judges applying the rules.[7] Yet before the rules even get to judges, they have to be created. Individual members of an elite set of committees—appointed by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court—are these creators.[8] And while we know a lot about the judges who apply the rules, we know very little about the people who make them.[9]

This Essay is the first to collect and quantify demographic data regarding the gender and racial composition of these committees.[10] It builds on my previous work by pulling back the curtain on this less visible group of individuals who shape the rules.[11] In all, there are six committees: Appellate, Bankruptcy, Civil Procedure, Criminal Procedure, Evidence, and Standing. These committees have variant histories and demographic compositions.[12] But they also have a significant feature in common: In general, their membership has been, and continues to be, dominated by white men.

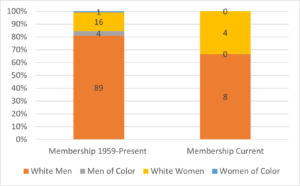

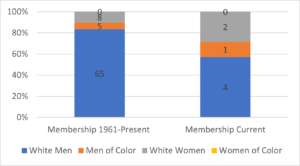

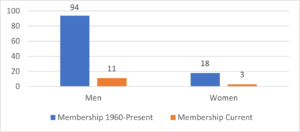

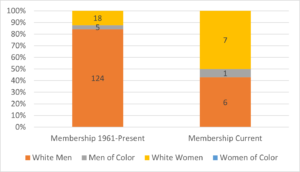

Of the 630 members that have served on a specialized set of committees responsible for drafting the federal rules for civil and criminal litigation, 513 of them have been white men, 78 white women, 32 men of color, and 7 women of color.[13] Of the current 64 members of the committees, 35 are white men, 21 are white women, 5 are men of color, and 3 are women of color.[14] What is shocking about these numbers is that the proportion of white people on the committees has been 94 percent over the committees’ history and is 92 percent today.[15] The committees are as white now as they were decades ago. And while more women have been added to the committees over the years—38 percent now compared to 13 percent historically—those women are also mostly white.[16] Of the 24 women currently serving on these committees, 21 are white women. Moreover, white men—while their numbers have declined—still have an outsized representation on today’s committees, occupying 55 percent of their positions.[17] The committees have been, and to a large degree remain, #SoWhiteMale. They are absolutely, without a doubt, #SoWhite.

A common response to this critique is that the rules are too technical to be tainted by misogyny or racism because one’s race or gender does not inform the neutral and apolitical work of rulemaking.[18] But it does. While the committee members are undeniably experts in their fields,[19] they still harbor biases. We all do. Moreover, the rulemakers’ work is not neutral. They must weigh interests, give primacy to particular values, and ultimately make tradeoffs. To do that work, rulemakers are informed by their ideology, politics, and identity.

In this Essay, I argue that identity matters. While identity does not define us, it informs our decisionmaking. Moreover, this decisionmaking takes place in a context in which identity is salient. Civil and criminal legal institutions—law schools, state bars, law firms, and the judiciary—long resisted allowing men of color and women into their ranks.[20] In addition, the criminal justice system has disproportionately targeted and punished people of color.[21] And recent work has exposed the racist underpinnings of the original civil and criminal rulemaking efforts, making it even harder to separate the rules from their racial implications.[22] The white, mostly male, hegemony of federal procedural rulemaking cannot separate itself from these realities. The Rules are part and parcel of these systems, and the individuals making the rules are subject to the biases embedded in those systems.

In short, this little-known yet powerful set of committees reflects the structural racism and sexism we confront throughout society today. This state of affairs is detrimental to the committees’ efficacy for three key reasons. First, the lack of representation on the committees delegitimizes the rulemaking process.[23] Second, the rules are suboptimal because critical voices are missing from the process.[24] And, finally, the rulemaking system has not yet accounted for the systemic exclusion of men of color and women from the legal profession.[25]

At the same time, to critique the committees as having made no progress in this area would be disingenuous. Progress has been made, albeit more in some committees than in others.[26] But the modest progress we have seen thus far is not enough, and it is not an excuse for failure to push further. Change is difficult, especially when it comes to race, gender, and representation. But unlike with many other institutions, here the path to institutional change is relatively straightforward: The Chief Justice is responsible for who sits on these committees, and he can change who he appoints.

This Essay proceeds in three parts. Part I presents data regarding all six committees’ membership over time. This Part compares each committee’s gender and racial composition to that of both the general population and relevant segments of the legal profession. Part II addresses the implications of identity on rulemaking. It argues that lack of diversity impacts the legitimacy of the rules, the quality of the rules, and the moral grounding of the rulemaking institution. Finally, Part III offers some observations on how the Chief Justice’s appointment process could be modified to put an end to the committees’ enduring problem of being #SoWhiteMale.

I. Federal Rulemaking and its Committee Members

Federal procedural rulemaking’s history began in the early 1900s, when even though some men of color and women attended law school in small numbers, the legal field remained dominated by white men.[27] This Part describes the rulemaking process and the separate committees that function within that process. It then presents the demographic data—both historical and current—for each of the committees.

A. Federal Procedural Rulemaking

1. The Rules Enabling Act & Process

The Rules Enabling Act of 1934 granted the Supreme Court the authority to promulgate uniform rules of procedure for the federal judiciary.[28] This was a major shift from past practice, which had required each federal court to abide by the procedural rules governing state courts in the state in which it sat.[29] The Rules Enabling Act was regarded as a sea change because it was. After its enactment, federal courts would follow a uniform set of rules of procedure.

Initially, the Supreme Court appointed an advisory committee to draft the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.[30] Soon after the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure went into effect in 1938, the U.S. Congress authorized the Court to appoint an advisory committee to draft the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.[31] After that committee completed its work, controversy[32] brewed over the rulemaking process. The Supreme Court dismantled the committees in 1955, only to reestablish them in 1957, but with a modified process for their operation.[33]

This process is the one that, for the most part, endures today.[34] The structure of federal civil and criminal procedural rulemaking relies heavily on six separate committees that were created by the Judicial Conference, the governing body of the federal courts.[35] The committee members are chosen by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.[36] The Standing Committee on the Federal Rules of Practice and Procedure sits atop five subject-specific advisory committees—Appellate, Bankruptcy, Civil, Criminal, and Evidence.[37] Each of these advisory committees studies its respective area of procedure and proposes rules and rule amendments.[38] Their proposals are then reviewed by the Standing Committee.[39] If the Standing Committee approves the rules, the proposals are published for public comment.[40] After that comment period, the Standing Committee, if it still approves of the proposals, forwards the proposals to the Judicial Conference.[41] The Judicial Conference then sends the proposals, upon approval, to the Supreme Court.[42] The Court considers the rules, and if it approves them, sends them on to Congress.[43] Congress then has until December 1 of that year to either modify or reject the proposals.[44] If Congress does not act on the rules—which is the norm—the rules become law.[45] The rulemaking process usually takes three years in total. It is multilayered, careful, and methodical.

The committees are the linchpin of this process. They generate and carry out ideas for rules and amendments,[46] and consider and weigh public comments.[47] So while the Supreme Court, the Judicial Conference, and Congress are part of the process—and quite a public part—these institutions are less engaged in the critical beginnings of which rules make it through the system and which rules do not. The committees are the gatekeepers.

The committees are relatively similar in structure. They are each led by a federal judge who serves as the committee chair.[48] And each committee employs a “reporter,” an academic member who does most of the drafting and research work but does not vote.[49] Committee memberships range from a low of eight voting members on the Evidence Committee to a high of fifteen on the Bankruptcy and Civil Rules Committees. The members are mostly federal district and appellate court judges, but some state judges serve on the committees, as do practitioners and members of the academy.[50] The members are appointed for three-year terms and are generally capped at two terms.[51] Again, all of these appointments are made solely by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.[52]

To paint the committees as monolithic, though, would be a mistake. All six committees have distinct histories and agendas. In the next Subpart, I briefly describe each committee, its history, and its rulemaking focus.

2. The Committees

The civil and criminal procedural rulemaking committees each have a unique history and ethos. The committees were created at different times, are charged with cultivating distinct types of procedural rules, and have distinct roles and limitations. As I discuss below, some of these unique characteristics might explain why the committees also have different demographic compositions, both historically and today.

The five advisory committees all sit below the Standing Committee on the Federal Rules of Practice and Procedure.[53] This committee does not generally originate rules, but it is the gatekeeper for all of the rules that come out of the advisory committees. If the Standing Committee does not approve a rule, the rule is done. Yet the Standing Committee was not part of the original rulemaking process,[54] but rather was created after the controversy surrounding the original Civil and Criminal Rules of Procedure.[55] When that process was reconstituted in 1958, the Standing Committee was formed.[56] This powerful committee is the face of the process and reports to the Judicial Conference. To say that an appointment to this committee is an honor is an understatement.[57] It is praiseworthy and sought out.

The Advisory Committee on Appellate Rules is a quieter, esteemed committee. The Appellate Committee has included among its past members Chief Justice Roberts, Associate Justice Alito, and Associate Justice Kavanaugh.[58] This committee was constituted in 1960 shortly after the Standing Committee was created.[59] It is responsible for rules governing how to file timely appeals,[60] what must be included in those appeals,[61] and what opinions may be cited as precedential and which may not, among others.[62] For litigants who are appealing their cases, these rules are incredibly meaningful.

The Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules differs from the other committees because it functioned for a while without express power from the Rules Enabling Act, which did not encompass bankruptcy. Before the Bankruptcy Rules were adopted, bankruptcy procedures were governed by General Orders in Bankruptcy and Official Forms, which were adopted by the Supreme Court.[63] In 1964, Congress amended the Rules Enabling Act to give the Supreme Court the authority to promulgate Bankruptcy Rules of Procedure.[64] The Bankruptcy Committee responds to congressional changes to the Bankruptcy Code and devises procedures for individual and corporate bankruptcy filings.[65]

The Advisory Committee on Civil Rules is the original rules committee. Appointed in 1934, this committee set the groundwork for the current committee process and rule structure.[66] The Civil Rules Committee is responsible for, among other things, creating and amending rules that govern how pleadings are filed,[67] how dispositive motions work,[68] and how information is exchanged between parties in discovery.[69] Every litigant who files or defends a case in a federal civil court is touched by this committee’s work.

The Advisory Committee on Criminal Rules is the second oldest committee. It was first constituted in 1941.[70] Like the Civil Rules Committee, this committee was responsible for determining how information would be exchanged between prosecutors and defendants and how prosecutors would be required to explain their charges.[71] While the U.S. Constitution and the Supreme Court’s interpretation of its protections heavily impact defendants in our federal criminal system, this committee also wields great power affecting how defendants fare.

Finally, the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules has the most colorful past of all of the committees. It was created in 1965 as part of a series of new committees that followed the creation of the Standing Committee.[72] It presented its first proposed rules to Congress in 1972, but the rules were met with controversy[73] centering on the committee’s choices regarding privilege.[74] In response to the controversy, Congress made significant changes to the Evidence Rules before adopting them in 1975.[75] The committee was then disbanded[76] and was not reconstituted until 1993.[77] Its power remains compromised, however, because the Evidence Rules from 1975 have become so entrenched in practice. This is partly because Chief Justice Rehnquist dictated that these rules rarely be amended, a practice that appears to continue under Chief Justice Roberts.[78] Even still, the Evidence Committee has an impact on litigants through its rulemaking decisions.[79]

In all, the work of these six committees is incredibly impactful. In the next Subpart, I will address the demographic makeup of these committees, both currently and over time. The unique work of each committee is, unsurprisingly, reflected in its demographic history.

B. The Numbers

Assessing the racial and gender composition of groups is fraught. On the one hand, these labels are an oversimplification. Race is a social construct and gender is fluid.[80] On the other hand, our country’s history of racial oppression and gender discrimination cannot be ignored, and that oppression and discrimination has been based on the simplified characteristics of “race” and “sex.” This Essay uses the labels of race and gender as shortcuts for a discussion of how diversity impacts the rulemaking process. But it does so at the risk of essentializing these characteristics and the people who possess them. Moreover, the term “woman” does not properly account for the intersectionality that impacts women of different races, sexual orientation, class, or other factors in different ways. When women are presented as a monolithic group, the experience of women with intersectional characteristics becomes invisible.[81] I will use these terms for ease of discussion, but I acknowledge the risk inherent in doing so as well as the deep body of literature that has unpacked the ways in which society largely ignores race and gender perspectives.[82]

With that foregrounding, in the tables and charts that follow I will use the U.S. Census Bureau’s racial designations despite their shortcomings.[83] These categorical labels, while imperfect, are necessary in order to describe and define the lack of diversity on the committee (and beyond).

1. The Standing Committee

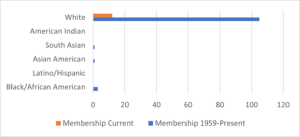

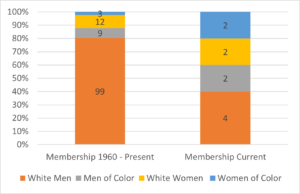

The Standing Committee is currently an all-white committee. Throughout its history, it has welcomed only five members of color, or roughly 5 percent of its membership, to its ranks. As the most prestigious and powerful of the committees, its lack of racial diversity is striking.

Figure 1: Standing Committee Composition by Race

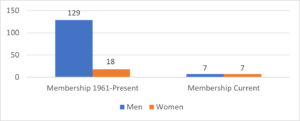

With respect to gender, the Standing Committee has been 85 percent male over the course of its history and is 67 percent male today.[84] There are four women on the Standing Committee, but like with many of the committees, all of those women are white.[85] Indeed, only one woman of color and four men of color have ever served on the committee.[86] This demonstrates that the Standing Committee has historically underrepresented women and men of color while overrepresenting white men, and to some degree, white women.

Figure 2: Standing Committee Composition by Gender

Figure 3: Standing Committee Composition by Race & Gender

2. The Appellate Rules Committee

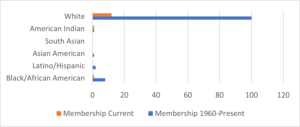

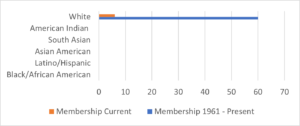

Like the Standing Committee, the Appellate Rules Committee has a predominantly white past. Over its history, the committee has been 94 percent white.[87] Currently, there is one man of color, a Black man, on the committee, but he is one of only five men of color to ever be a member of this elite committee.[88]

Figure 4: Appellate Committee Composition by Race

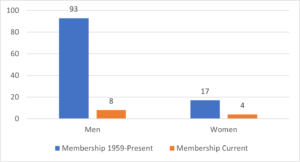

The Appellate Rules Committee is also very male. Over its history, men have made up 90 percent of the committee,[89] and they make up 71 percent of it today.[90] Like with the Standing Committee, however, it is at the intersection of race and gender where we learn the most. No women of color have ever served on the Appellate Rules Committee, and men of color have only served in infinitesimal numbers.[91]

Figure 5: Appellate Committee Composition by Gender

Figure 6: Appellate Committee Composition by Race & Gender

3. The Bankruptcy Committee

The Bankruptcy Committee has been the most racially diverse of the committees over its history. But even this committee has been overwhelmingly white, with its white membership over time coming in at 89 percent.[92] In all, twelve individuals of color have served on this committee.[93] Today, however, it does not lead in diversity. Two of its members, or 14 percent, are people of color—one member is Indigenous and one is Black.[94]

Figure 7: Bankruptcy Committee by Race

As to gender, the Bankruptcy Committee has also been the most diverse historically. Men have made up 84 percent of the committee’s membership during its history, just below the Standing and Evidence Committees.[95] But today the Bankruptcy Committee is not the most gender diverse, as 79 percent of its current membership is male.[96] With respect to race and gender, while the Bankruptcy Committee has been the most racially diverse historically with twelve members of color in total, nine of those members were men.[97] Only three women of color in total have served on the committee and only one woman of color serves on it now.[98]

Figure 8: Bankruptcy Committee Composition by Gender

Figure 9: Bankruptcy Committee by Race & Gender

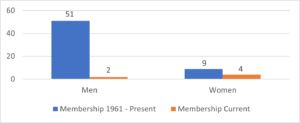

The Civil Rules Committee

My data for the Civil Rules Committee, shown below, have been updated since my previous article.[99] The Civil Rules Committee has been and remains dominated by white people. Only five men of color, or 3 percent of the committee’s membership over time, have ever served on the committee.[100] Currently, the committee has only one member of color, a Black person.[101]

Figure 10: Civil Rules Committee Composition by Race

One major change since the publication of my previous article is that there are now seven women on the Civil Rules Committee, the most to ever simultaneously serve on any rulemaking committee.[102] But every single woman on the committee is (and always has been) white.[103] The following graphs show the improvement in gender composition today, but also demonstrate the complete lack of women of color. To put it more starkly, while the committee is now 50 percent women, it is still 93 percent white.[104]

Figure 11: Civil Rules Committee Composition by Gender

Figure 12: Civil Rules Committee Composition by Race & Gender

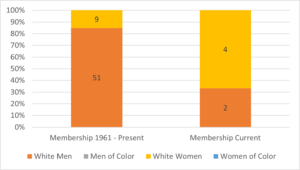

5. The Criminal Rules Committee

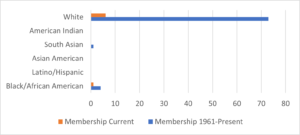

The Criminal Rules Committee is one of the most racially diverse committees today, with four members of color. While the committee has been 90 percent white over its history, it is currently 64 percent white.[105] While these numbers still overrepresent white people, they are an improvement and a contrast from the other committees, which currently range between 86 percent to 100 percent in white membership.[106]

Figure 13: Criminal Rules Committee Composition by Race

The Criminal Rules Committee has been 88 percent male over its history, but is 64 percent male today.[107] Three women of color have served on the committee since it began, two of whom are current members.[108] The Criminal Rules Committee is an outlier in this respect, but as I discuss below, two women of color on the current committee is still underrepresentative of both the pool of available candidates and the population subject to the Criminal Rules.[109]

Figure 14: Criminal Rules Committee Composition by Gender

Figure 15: Criminal Rules Committee by Race & Gender

6. The Evidence Rules Committee

Unlike all of the other committees, the Evidence Rules Committee has always been and remains an all-white committee.[110] This is despite the fact that the evidence rules have a significant bearing on criminal trials and that nearly 38 percent of people currently incarcerated in federal prisons are Black.[111]

Figure 16: Evidence Committee Composition by Race

Another interesting feature of the Evidence Rules Committee relates to gender. Over its history, the Committee has been 85 percent men, but currently men make up only 33 percent of the committee.[112] One thing to note is that the Evidence Rules Committee, as currently constituted, is one of the smallest committees with only seven voting members, six of whom are appointed by Chief Justice Roberts. In addition, even though the committee boasts higher numbers of women, it has never included a woman of color.[113]

Figure 17: Evidence Committee Composition by Gender

Figure 18: Evidence Committee Composition by Race & Gender

7. Committee Leadership

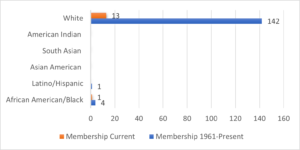

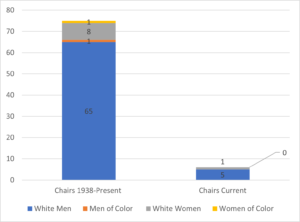

A final category with which to measure the committees’ diversity is their chairs—the leaders of each committee—and the reporters, law professors who draft the rules and assist the chairs in leading their committee’s work. Both positions are prestigious. Of all the committee chairs over time, 97 percent have been white and 88 percent have been men.[114] Only 2 of the 75 total chairs have ever been people of color: Judge Laura Swain, a Black woman, served as Chair of the Bankruptcy Rules Committee and Judge Carl E. Stewart, a Black man, served as Chair of the Appellate Rules Committee.[115] Currently, of the six committees, five are chaired by white men and one (Evidence) is chaired by a white woman.[116]

Figure 19: Committee Chairs by Race & Gender

Of the reporters to all of the committees over time, 97 percent have been white and 80 percent have been men. Troy McKenzie, a Professor of Law at NYU, is the only person of color to ever serve as a reporter.[117] The current reporters are evenly split, with three white men and three white women.[118] Today, every chair and reporter is white. Like with committee membership, these numbers reflect the dominance of white men in leadership as chairs and of white people as reporters.

Figure 20: Committee Reporters by Race & Gender

C. The Context

This committee data demonstrate that although some progress has been made, it has been spotty and slow. While some committees, like the Civil and Evidence Committees, have increased their female membership, they have added only white women. Other committees, like the Bankruptcy and Criminal Rules Committees, have marginally higher numbers of members of color, including women of color, but still grossly underrepresent the pool of candidates that could serve on each committee. And, as I discuss below, the Criminal, Evidence, and Bankruptcy Committees are unrepresentative of the populations that the rules they promulgate most strongly affect.

One deflection of this critique of demographic composition is that the pool of candidates for these types of committees already underrepresents the general population, leaving the Chief Justice with little choice but to appoint less diverse committees. In other words, because there are few lawyers of color or lawyers who are women, the committees are simply a reflection of that pipeline problem.

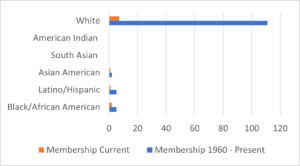

This is a common response, so to put these numbers into context, the table below sets forth the composition of all of the committees by race—both historically and currently. Next, to reflect the general population, the table lists the most recent Census Bureau numbers by race (as of July 2019),[119] followed by a racial breakdown of lawyers and federal district court judges. The pool of candidates for committee positions largely consists of federal district court judges and lawyers; thus, the table below focuses on these two major categories.[120]

Table 1: Committee Membership Racial Identity Compared to General Population,

Law Practice Population, & Judiciary

| Race | Committee Membership (1934–2020) | Current Committee Membership | U.S. Population (Census) | Legal Practice[121] | Federal District Court Judges[122] |

| White (non Latinx/Hispanic) | 94% | 92% | 60.1% | 85.5% | 73% |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 1% | 2% | 18.5% | 5.1% | 9% |

| Black/African American | 4% | 8% | 13.4% | 4.6% | 13% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0% | 2% | 1.3% | ** | ** |

| Asian | 1% | 2% | 5.9% | 4.8% | 4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0% | 0% | 0.2% | ** | ** |

Table 1 shows that white people have been overrepresented on the committees over time and remain overrepresented today. This is true with respect to every metric—general population, legal practice, and federal district court judges. Conversely, every racial designation is underrepresented on the committees by every count.[123] For example, while Latino/Hispanic individuals hold 9 percent of federal district court judgeships and make up about 5 percent of the bar, they have made up less than 1 percent of the committees over time and occupy only 2 percent of the committee seats today.

The story is roughly the same for other individuals of color. For instance, while Black individuals hold 13 percent of federal district court judgeships, they have held 4 percent of the committee positions over time and only 8 percent of those committee positions today. Indeed, white people, mostly white men, have dominated and continue to dominate the committees’ composition in numbers that outpace their already outsized representation as lawyers and judges.

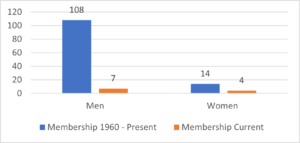

The committees’ gender composition has shown more improvement, but as with the racial data, men have been and remain overrepresented. Unlike with race, the current committee membership roughly reflects both the number of women in legal practice and serving as district court judges, but still does not reflect the general population.

Table 2: Committee Membership Gender Identity Compared to General Population, Law Practice Population, & Judiciary

| Gender | Committee Membership (1943–2020) | Current Committee Membership | U.S. Population (Census)[124] | Legal Practice[125] | Federal District Court Judges[126] |

| Male | 87% | 63% | 49.2% | 64% | 67% |

| Female | 13% | 37% | 50.8% | 36% | 33% |

As Table 2 demonstrates, women hold 33 percent of federal district court judgeships, make up 36 percent of practicing lawyers, and hold 37 percent of current committee positions. This is a recent and welcome development. The downside, of course, is that at the intersection of race and gender, women of color remain grossly underrepresented, holding only 3 of the current 64 committee seats, or 4.6 percent. This is true even though women of color hold 11.9 percent of federal judgeships[127] and make up 14.5 percent of practicing lawyers.[128]

II. Rulemaking and Diversity

The federal procedural rulemaking committees are a small but significant reflection of systemic racism and sexism. In this Part, I discuss why a lack of diversity on these committees is problematic.[129] The lack of representation on these committees calls the legitimacy of the rulemaking process into question, negatively impacts the quality of the rules, and is morally incongruous with the ethical commitments of the bench and bar.

First, the legitimacy of the committees’ work is called into question by the committees’ historical and current compositions. This is because the committees not only fail to reflect the legal pool of talent from which their members are drawn,[130] but they also fail to reflect the populations most impacted by their rules.[131] For example, the criminal justice system disproportionately pursues, prosecutes, and punishes Black men. Black people—primarily Black men—represent 38 percent of the federal prison population.[132] Yet, only 18 percent of the Criminal Rules Committee’s members are Black.[133] Over the course of the committee’s history, that number has been a mere 4 percent.[134] Similarly, evidentiary rules significantly affect the ease or difficulty with which criminal defendants are incarcerated, yet there has never been a person of color on the Evidence Committee.

Similarly, individual Chapter 13 bankruptcy filings are disproportionately filed by Black people, and those filings have much lower rates of discharge than the Chapter 7 filings made by mostly white filers.[135] Yet, the composition of the Bankruptcy Committee fails to reflect this reality with only one Black member, or 7 percent of its membership.[136] While it has been one of the most diverse committees over its history, relatively speaking, it does not come close to representing the population most impacted by the rules it promulgates. When populations do not see themselves in the power structures that dictate the rules governing their lives, the legitimacy of those structures is called into question.[137]

Second, there is good evidence that if the rules committees were more diverse, the rules they produce would be of even higher quality. There are myriad studies on the benefits of racial and gender diversity. Business studies show that corporate boards that include more women yield higher profits.[138] Social science studies have shown that more diverse decisionmaking bodies, including juries, produce more accurate results.[139] And judicial studies show that diversity leads to similarly positive impacts on the bench, such as the impact of female judges on their male counterparts’ decisionmaking, including but not limited to, an increase in the likelihood that gender discrimination plaintiffs prevail.[140] While there are also studies demonstrating how diversity can cause friction and have certain negative impacts on group dynamics, the overall picture is that diversity has a positive impact on groups’ work product.[141] This is largely because additional perspectives mitigate the blind spots decisionmaking bodies might otherwise have.[142] The rulemaking committees are no different.

One response to this argument is that in order to prove diversity matters, it is necessary to demonstrate how a past rule might have been improved with diverse committee membership. While an appealing question, it is something of a red herring. There is no way to go back and surmise how a rule or rule change might have been differently constituted had there been more men of color or women on the committees. We can speculate, of course, but the most surefire way to know whether or not a more diverse committee produces different rules is to create those committees. Moreover, the evidence is on the side of diversity.[143] To some degree, the task to demonstrate how history would change with more diversity is a distraction from what we know to be true, and that is that diversity makes a difference.

Finally, the bench, the bar, and committee members have a moral obligation to remedy the committees’ lack of diversity.[144] As discussed above, legal institutions long excluded men of color and women from every aspect of the profession.[145] And even when men of color and women were admitted into law schools or to practice, the resistance to their inclusion was hostile.[146] To this day, structural racism and sexism prevent men of color and women from being full and welcome participants in many legal institutions.[147] It is this history—and this current reality—that should compel the bench, the bar, and committee members to demand greater diversity in committees.

III. Potential Reforms

A Federal Judicial Center (FJC) report was published in the early 1980s in response to then–Chief Justice Burger’s request to review the entire rulemaking process.[148] The over 150-page report is full of critiques and proposed solutions. The report drew on opinions and ideas expressed at an FJC-convened conference, a professor’s discussion paper, and other published literature regarding the rulemaking process.[149] Two contributors to the report—Judge Jack Weinstein and Howard Lesnick—argued that there should be more “representation of the ‘under-represented,’” whom they identified as “the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, women, children, and those generally less able to call on the services of the legal profession.”[150] The response from other contributors was to question “whether there can really be a ‘minority’ or ‘women’s’ position on the types of question that come before the committees, and they object[ed] to the charade of ‘token’ representation.”[151] More specifically, Geoffrey Hazard questioned “whether committees composed differently would have considered any feasible proposals that were not in fact considered in connection with rules promulgated in the past.”[152] Hazard also warned that “radical-activist” views on committees—presumably brought about merely through an increase in diversity—would be problematic.[153]

This document from almost forty years ago is striking as a representation of how our debates regarding diversity are evergreen. It is also a testament to how little progress has been made. Discussion and commentary on diversity is a necessary piece of the solution, and this Essay contributes to that. But the bottom line is that those with power must act, and swiftly.

This Essay is a call to action. There have been many critiques of the Chief Justice’s power over particular appointments. Scholars like James Pfander, for example, have persuasively questioned the Chief Justice’s constitutional authority to make certain appointments[154] as well as the wisdom of affording the Chief this power.[155] While I tend to agree with Pfander’s criticisms, as a practical matter, the position is a nonstarter. The Chief makes these appointments, and there is very little political will to change that reality.[156]

Thus, the responsibility to enact change lies with the Chief Justice and with those who aid him in selecting committee members. It lies with the current committee members who have influence and who can propose names to the Chief. And it lies with powerful members of the bench and bar who can take up this call to action and demand that the Chief Justice do better. As one scholar has explained:

[B]ecause the profession self-regulates and resists attempts by others to regulate it, it falls to the profession to battle discrimination and under-representation and to pursue diversity within its ranks. If only because it continues to fight against external regulation, the legal profession must lead in the fight for diversity and equality.[157]It is, therefore, the duty of the Chief Justice and all who have influence with him to remedy the lack of diversity on the rulemaking committees.

The current system of appointments is something of a black box, but conversations with relevant players indicate that calls for nominations go out to the chief judges in each of the appellate circuits. Currently, federal appellate courts are 83 percent white and 74 percent male.[158] It is no surprise, then, that a system that relies on informal word of mouth for appointments demographically reflects the mouths from which those nominations are made. One improvement would be to send a call for nominations more broadly—to affinity bar groups, for example. Another improvement would be for the Chief Justice to establish a nominating committee with the primary charge of increasing diversity on the rulemaking committees measured against specific deadlines and milestones.

These types of reforms would go a long way toward diversifying the committees, but the bottom line is the same. The lack of diversity on these committees is not inevitable. It is a choice, and the remedy is simple: Recognize the importance of diversity and commit to increasing the number of men and women of color on these committees. The rulemaking process will be better for it. The rules will be better for it. And, most importantly, it is the right thing to do.

Conclusion

The federal civil and criminal procedural rulemaking committees are powerful arbiters of the rules we must play by in our civil and criminal justice systems. The fact that their composition has been 94 percent white over time and is 92 percent white today should give every member of the committees, the bench, and the bar great pause. This is a problem. The composition of the committees impacts the legitimacy of the process, the quality of the rules, and the morality of our profession. The call to action has been made; let us hope it is answered. The rulemaking committees need not be #SoWhiteMale.

[1]. See, e.g., Fed. R. Evid. 401–15.

[2]. See, e.g., Fed. R. Civ. P. 26–37.

[3]. See, e.g., Fed. R. App. P. 3–12.

[4]. See, e.g., Fed. R. Bankr. P. 1002–18.

[5]. See, e.g., Fed. R. Crim. P. 42.

[6]. See supra notes 1–5.

[7]. Jonathan K. Stubbs, A Demographic History of Federal Judicial Appointments by Sex and Race: 1789–2016, 26 Berkeley La Raza L.J. 92, 117 (2016) (examining the demographics of judges on federal courts of general jurisdiction); Victor D. Quintanilla, Critical Race Empiricism: A New Means to Measure Civil Procedure, 3 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 187 (2013) (studying how a judge’s race may impact grant rates on motions to dismiss in race discrimination cases).

[8]. See infra Part I.

[9]. See infra Part I.

[10]. One study assessed the impact of the race and gender on a federal judge’s chances for gaining appointment to the Civil Rules Committee, but it did not assess the overall demographics of the committee’s membership over time. See Stephen B. Burbank & Sean Farhang, Rights and Retrenchment: The Counterrevolution Against Federal Litigation (2017). Committees other than the Civil Rules Committee have never been assessed for their demographic composition.

[11]. Brooke D. Coleman, #SoWhiteMale: Federal Civil Rulemaking, 113 Nw. U. L. Rev. 407 (2018).

[12]. See infra Part I.

[13]. See infra Subpart I.B. My research assistants and I created a dataset by compiling a list of all six committees and their membership. We then coded the data for race and gender. The dataset also includes the committee members’ years of service, occupations, and geographic locations. On the rare occasion in which the race of a committee member could not be confirmed via research, the assumption was made that the member was white. Over all six committees, approximately fifteen committee members were in this category. See Brooke D. Coleman, Federal Procedural Rules Committee Dataset (Oct. 1, 2020) (unpublished dataset) (on file with author) [hereinafter Rules Committee Dataset].

[14]. U.S. Cts., Rules Committees—Chairs and Reporters (2020), https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/oct_2020_-_dec_2020_committee_roster_for_web.pdf [https://perma.cc/6BYQ-VSPL].

[15]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[16]. Id.

[17]. Id.

[18]. See Dana Shocair Reda, What Does It Mean to Say That Procedure Is Political?, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 2203, 2207 (2017) (“The Committee is saddled with the burden of holding itself out as a body whose decisions are apolitical. Indeed, the Committee’s existence relies on the premise that it can engage in a largely expert and technical task best left to the judiciary rather than the political branches. To the extent that its decisions are understood to be political rather than ‘procedural,’ the legitimacy of its actions is called into question.” (footnote omitted)); Richard L. Marcus, Of Babies and Bathwater: The Prospects for Procedural Progress, 59 Brook. L. Rev. 761, 774 (1993) (advocating for a neutral approach to rulemaking, Marcus, a current associate reporter for the Civil Rules Committee, explained that “at the heart of a neutralist perspective on procedure is an honest attempt to fashion rules that will fairly accommodate the concerns of accuracy, participation and efficiency” and that “[a]lthough attitudes toward these concerns may be colored by matters of ‘ideology,’ that is not somehow a trump that makes the entire exercise a charade”).

[19]. See Charles Gardner Geyh, Paradise Lost, Paradigm Found: Redefining the Judiciary’s Imperiled Role in Congress, 71 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1165, 1169 (1996) (noting that the Rules Enabling Act, which provided the basis for the Civil Procedure committee, “envisioned procedural rulemaking as an essentially technical undertaking best left in the expert hands of judges”).

[20]. See Veronica Root Martinez, Combating Silence in the Profession, 105 Va. L. Rev. 805, 805 (2019) (“For decades, the legal profession purposefully excluded women, religious minorities, and people of color from its ranks, while instilling a select group of individuals with the privilege of power and prestige.”); Daria Roithmayr, Deconstructing the Distinction Between Bias and Merit, 85 Calif. L. Rev. 1449, 1449 (1997) (“Reviewing the history of law school admissions standards, she demonstrates that choices about what constitutes socially valuable ability in the legal profession and legal education historically were made in the context of the profession’s explicitly race-conscious effort to exclude immigrants and people of color.”); Daria Roithmayr, Barriers to Entry: A Market Lock-in Model of Discrimination, 86 Va. L. Rev. 727, 734–35 (2000) (“At the turn of the century, whites intentionally excluded people of color from participating in the establishment of the de facto standard in the legal profession. Currently, a culturally specific standard that is locked into the market creates significant barriers to entry for people of color. Far from a level playing field, competition takes place in markets where white monopoly power may have become self-reinforcing.”); Lorenzo Trujillo, The Relationship Between Law School and the Bar Exam: A Look at Assessment and Student Success, 78 U. Colo. L. Rev. 69, 77 (2007) (explaining how the bar exam excludes students of color).

[21]. See generally Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010) (describing and critiquing how mass incarceration is a modern form of oppression intended to perpetuate the inequalities established through the enslavement of Black men and women); Research Working Group & Task Force on Race, The Criminal Justice System, Preliminary Report on Race and Washington’s Criminal Justice System, 35 Seattle U. L. Rev. 623, 627 (2012) (“Today, minority racial and ethnic groups remain disproportionately represented in Washington State’s court, prison, and jail populations, relative to their share of the state’s general population. The fact of racial and ethnic disproportionality in our criminal justice system is indisputable.”).

[22]. The civil and criminal rulemaking efforts occurred in a time of great racial and gender inequality. And while many of the rulemakers were cast as progressive, the institutions that gave rise the rules and the rulemakers were simultaneously part of this oppression. See, e.g., Ion Meyn, Constructing Separate and Unequal Courtrooms, Ariz. L. Rev. (manuscript at 3) (forthcoming 2020) (“Reform occurred in a society committed to racial hierarchy and that linked blackness to criminality, used criminal law to maintain white racial privilege, and employed procedure to legitimate law’s racial ordering. These entrenched norms would be expected to, and did, shape procedural design.”).

[23]. See infra Part II.

[24]. See infra Part II.

[25]. See infra Part II.

[26]. See infra Subpart I.B.

[27]. Brooke D. Coleman, A Legal Fempire?: Women in Complex Litigation, 93 Ind. L.J. 617, 618–25 (2018).

[28]. 28 U.S.C. § 2072. For a comprehensive description of the process that led to the adoption of the Rules Enabling Act, see generally Stephen B. Burbank, The Rules Enabling Act of 1934, 130 U. Pa. L. Rev.1015 (1982) (providing the seminal historical account of the Rules Enabling Act and its adoption); Brooke D. Coleman, Recovering Access: Rethinking the Structure of Federal Civil Rulemaking, 39 N.M. L. Rev. 261 (2009) (recounting the history of how the Rules Enabling Act was adopted and how access to justice was a strong concern informing its adoption).

[29]. This requirement was imposed by the Act’s predecessor, the Conformity Act of 1872, ch. 255, § 6, 17 Stat. 196, 197.

[30]. The Court appointed an advisory committee in 1935, naming former Attorney General William D. Mitchell as the chair and then–Yale Law School Dean Charles E. Clark as the reporter. Order Appointing Committee to Draft Unified System of Equity and Law Rules, 295 U.S. 774 (1934); Paul V. Niemeyer, Revisiting the 1938 Rules Experiment, 71 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 2157, 2161 (2014).

[31]. Meyn, supra note 22, at 7.

[32]. After the original Civil and Criminal Rules were adopted, some viewed the U.S. Supreme Court’s role in continued rulemaking as inattentive. See, e.g., Coleman, supra note 28, at 276–77. This critique came to a head in the 1950s when the Supreme Court disbanded the committees only to later reconstitute them with new administrative procedures. Id.

[33]. See Daniel R. Coquillette, A Self-Study of Federal Judicial Rulemaking: A Report From the Subcommittee on Long Range Planning, 168 F.R.D. 679, 685–86 (1995).

[34]. Id.

[35]. The Judicial Conference of the United States was established by the U.S. Congress. It oversees the business of the federal courts. Governance & the Judicial Conference, U.S. Cts., https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/governance-judicial-conference [https://perma.cc/3EZY-Y7TY].

[36]. Overview for the Bench, Bar, and Public, U.S. Cts., http://www.uscourts.gov/rules-policies/about-rulemaking-process/how-rulemaking-process-works/overview-bench-bar-and-public [https://perma.cc/UCY4-M9KR].

[37]. Coquillette, supra note 33, at 687.

[38]. Overview for the Bench, Bar, and Public, supra note 36.

[39]. Id.

[40]. Id.

[41]. Id.

[42]. Id.

[43]. Id.

[44]. Id.

[45]. Id.

[46]. Coquillette, supra note 33, at 689 (“By delegation from the Judicial Conference, each Advisory Committee is charged to carry out a ‘continuous study of the operation and effect of the general rules of practice and procedure’ in its particular field.”).

[47]. Id.

[48]. Winifred R. Brown, Fed. Judicial Ctr., Federal Rulemaking: Problems and Possibilities 9–12 (1981).

[49]. Id.

[50]. See id. Most of the committees also include representatives from the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Coquillete, supra note 33, at 696. The criminal committee and the evidence committee each includes a representative from a Federal Defender’s office. Id. The data in Subpart I.B do not include these committee members in the membership calculations because the DOJ members and the Federal Defender members are not appointed by the Chief Justice. These representatives are chosen by their respective department leadership. These determinations are internal, and therefore not publicly available, but for some committees, the appointment is positional. For example, the DOJ Assistant Attorney General serves on the Civil Rules Committee and the Deputy Attorney General serves on the Standing Committee.

[51]. Overview for the Bench, Bar, and Public, supra note 36.

[52]. Id.

[53]. Id.

[54]. Coquillette, supra note 33, at 686.

[55]. See id.

[56]. Id.

[57]. See, e.g., A. Leo Levin, Beyond Techniques of Case Management: The Challenge of the Civil Justice Reform Act of 1990, 67 St. John’s L. Rev. 877, 899 (1993) (referring to “[t]he prestigious chair of the Standing Committee on Practice and Procedure, Judge Robert E. Keeton”); Stephen A. Saltzburg, Philip D. Reed Professorship in Civil Justice and Dispute Resolution the Future of Class Actions in Mass Tort Cases: A Roundtable Discussion, 66 Fordham L. Rev. 1657, 1659 (1998) (“Judge Stotler holds the important and prestigious position of Chair of the Judicial Conference Standing Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure. . . . Judge Stotler is a member of the American Law Institute and of the Executive Committee of the National Conference of Federal Judges.”).

[58]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[59]. Catherine T. Struve, History of the Appellate Rules, in 16A Federal Practice & Procedure § 3946 (Wright & Miller, 5th ed. 2020).

[60]. See Fed. R. App. P. 3–4.

[61]. See Fed. R. App. P. 3, 10.

[62]. See Fed. R. App. P. 32.1.

[63]. Lawrence P. King, The History and Development of the Bankruptcy Rules, 70 Am. Bankr. L.J. 217, 217 (1996).

[64]. Alan N. Resnick, The Bankruptcy Rulemaking Process, 70 Am. Bankr. L.J. 245, 246 (1996). The Bankruptcy Rules process falls under 28 U.S.C. § 2075, not § 2072. Resnick, supra, at 262.

[65]. Like other committees, the Bankruptcy Committee includes members not appointed by the Chief Justice. For example, “the Director of the Commercial Litigation Branch of the Civil Division of the Department of Justice serves as an ex officio member . . . .” Id. at 248–49 (emphasis omitted). In addition, the Director of the Executive Office for United States Trustees and one bankruptcy clerk participate in the committee, but do not vote. Id. at 249.

[66]. The committee was disbanded in 1955, but reconstituted in 1960. Coquillette, supra note 33, at 685.

[67]. Fed. R. Civ. P. 8.

[68]. Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6), 56.

[69]. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26–37.

[70]. Meyn, supra note 22, at 7.

[71]. See Fed. R. Crim. P. 3–5, 10–12.4.

[72]. Coquillette, supra note 33, at 686.

[73]. See id.

[74]. See id. Congress was displeased with the Evidence Committee’s choice to codify certain state and common law privileges, but not others. Jack H. Friedenthal, The Rulemaking Power of the Supreme Court: A Contemporary Crisis, 27 Stan. L. Rev. 673, 683–84 (1975) (discussing how the committee proposed a rule prohibiting forced testimony against one’s spouse, but did not propose a rule privileging all spousal communications).

[75]. Id. A longterm effect of this brouhaha is that Congress must affirmatively approve any change to the Evidence Rules that addresses privilege. 28 U.S.C. § 2074(b).

[76]. See Coquillette, supra note 33, at 686.

[77]. Id.; see also Daniel J. Capra & Liesa L. Richter, Poetry in Motion: The Federal Rules of Evidence and Forward Progress as an Imperative, 99 B.U. L. Rev. 1873, 1877 (2019) (describing this part of the Evidence Committee’s history).

[78]. See Capra & Richter, supra note 77, at 1876.

[79]. Cf. id. at 1879 (“There are other, more foundational irregularities in the operation of the Rules that cannot be ignored, however. When the Evidence Rules are subject to unconstitutional application, when the federal courts are split as to their proper interpretation, or when old rules are ill-suited to contemporary litigation or are needlessly complex, amendments should be pursued.”).

[80]. Janet E. Helm, Introduction: Review of Racial Identity Terminology, in Black and White Racial Identity: Theory, Research, and Practice 3, 3 (Janet E. Helm ed., 1990) (stating that “the term ‘racial identity’ actually refers to a sense of group or collective identity based on one’s perception that he or she shares a common racial heritage with a particular racial group”).

[81]. See Kimberlé Crenshaw, Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color, 43 Stan. L. Rev. 1241, 1242–44 (1991) (describing the intersectional position of women of color and their marginalization within feminist discourse); Angela P. Harris, Race and Essentialism in Feminist Legal Theory, 42Stan. L. Rev. 581, 585 (1990) (discussing the need the feminist movement to engage and embrace intersectional identities).

[82]. Critical Race Theorists have done all of the heavy lifting for this work. Without their work, essays like mine would never even be written. The body of work is too vast to cite, but I have listed some essential sources in this footnote for those who would like to explore further. See, e.g., Derrick A. Bell, Jr., Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest Convergence Dilemma, 93 Harv. L. Rev. 518 (1980); Derrick A. Bell, Jr., After We’re Gone: Prudent Speculations on America in a Post-Racial Epoch, 34 St. Louis U. L.J. 393 (1990); Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Race, Reform, and Retrenchment: Transformation and Legitimation in Antidiscrimination Law, 101 Harv. L. Rev. 1331 (1988); Harris, supra note 81; Gerald P. López, Reconceiving Civil Rights Practice: Seven Weeks in the Life of a Rebellious Collaboration, 77 Geo. L.J. 1603 (1989); Mari J. Matsuda, Looking to the Bottom: Critical Legal Studies and Reparations, 22 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 323 (1987); Richard Delgado & Jean Stefancic, Critical Race Theory: An Introduction (3d ed. 1995). In addition, while beyond the scope of this Essay, there are additional meaningful inquiries that could be made into the committees’ compositions, such as sexual orientation, class, and disability status. See, e.g., Kathleen Dillon Narko, “Inclusion Means Including Us, Too”: Disability and Diversity in Law Schools, Fed. Law., Jan./Feb. 2017, at 22, 22–23, https://www.fedbar.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Inclusion-pdf-1.pdf [https://perma.cc/S5BH-NGNH] (arguing for greater consideration of disability’s impact on those in the legal field).

[83]. See Kenneth Prewitt, Fix the Census’ Archaic Racial Categories, N.Y. Times (Aug. 21, 2013), http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/22/opinion/fix-the-census-archaic-racial-categories.html [https://perma.cc/9T7P-ZMNR] (critiquing the current designations and calling for a new approach to collecting census data).

[84]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[85]. Id.

[86]. Id.

[87]. Id.

[88]. Id.

[89]. Id.

[90]. Id.

[91]. Id.

[92]. Id.

[93]. Id.

[94]. Id.

[95]. Id.

[96]. Id.

[97]. Id.

[98]. Id.

[99]. See Coleman, supra note 11.

[100]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[101]. Id.

[102]. Id.

[103]. Id.

[104]. Id.

[105]. Id.

[106]. Id.

[107]. Id.

[108]. Id.

[109]. See infra notes 119–128 and accompanying text; infra Part II.

[110]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[111]. See Inmate Race, Fed. Bureau Prisons, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp [https://perma.cc/D9FA-LN6F].

[112]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[113]. Id.

[114]. Id.

[115]. Id.

[116]. Id.

[117]. Id.

[118]. Id.

[119]. QuickFacts, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 [https://perma.cc/SP8H-V34S].

[120]. Federal district court judges make up most of the committees’ membership. Cf. Brooke D. Coleman, One Percent Procedure, 91 Wash. L. Rev. 1005, 1017 (2016) (“The [C]ommittee has profoundly changed between 1971 and the present day, with judges taking up more seats than practitioners and academics combined.”).

[121]. See Elizabeth Chambliss, The Demographics of the Profession, in IILP Review 2017: The State of Diversity and Inclusion in the Legal Profession 13, 18 tbl.1 (2017) [hereinafter ILLP Review 2017], http://www.theiilp.com/resources/Pictures/IILP_2016_Final_LowRes.pdf [https://perma.cc/M9MS-L8B2]. The numbers reflect data for 2015.

[122]. Danielle Root, Jake Faleschini & Grace Oyenubi, Building a More Inclusive Federal Judiciary, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Oct. 3, 2019, 8:15 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/courts/reports/2019/10/03/475359/building-inclusive-federal-judiciary [https://perma.cc/2BUS-HUTP]. These numbers represent active judges and do not include judges on senior status.

** The data provided in the IILP Review did not break down percentages in these two categories. ILLP Review 2017, supra note 119.

[123]. The sole exception is Black lawyers (4.6 percent) relative to current Black committee members (8 percent). As discussed though, judges make up a substantial portion of the committees, and the current Black committee membership (8 percent) falls woefully short of the percentage of Black federal district court judges (13 percent). See Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13; supra Table 1.

[124]. QuickFacts, supra note 119.

[125]. Chambliss, supra note 121, at 18 tbl.2. The numbers reflect data for 2015.

[126]. Root et al., supra note 122. These numbers represent active judges and do not include judges on senior status.

[127]. Barry J. McMillion, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R43426, U.S. Circuit and District Court Judges: Profile of Select Characteristics 20 fig.12 (2017).

[128]. Chambliss, supra note 121. This percentage reflects data from 2015.

[129]. Again, this critique stands on the shoulders of Critical Race Theorists, and their groundbreaking work. See supra note 82.

[130]. See supra Subpart I.B.

[131]. See A.B.A. Presidential Diversity Initiative, Diversity in the Legal Profession: The Next Steps 9 (2010) (“Without a diverse bench and bar, the rule of law is weakened as the people see and come to distrust their exclusion from the mechanisms of justice.”).

[132]. Inmate Race, supra note 111.

[133]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[134]. Id.

[135]. See Paul Kiel & Hannah Fresques, Data Analysis: Bankruptcy and Race in America, ProPublica (Sept. 27, 2017), https://projects.propublica.org/graphics/bankruptcy-data-analysis [https://perma.cc/Q5RE-UFA5].

[136]. Rules Committee Dataset, supra note 13.

[137]. Justice Kagan described this by saying, “People look at an institution and they see people who are like them, who share their experiences, who they imagine share their set of values, and that’s a sort of natural thing and they feel more comfortable if that occurs.” Adam Liptak, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan Muse Over a Cookie-Cutter Supreme Court, N.Y. Times (Sept. 5, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/06/us/politics/sotomayor-kagan-supreme-court.html [https://perma.cc/2QBH-4K7B].

[138]. See, e.g., Daniel Rock & Heidi Grant, Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Nov. 4, 2016), https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter [https://perma.cc/SFZ6-V4LH].

[139]. Samuel Somers, On Racial Diversity and Group Decision Making: Identifying Multiple Effects of Racial Composition on Jury Deliberations, 90 J. Personality & Soc. Psych. 597, 605 (2006).

[140]. See Jennifer L. Peresie, Female Judges Matter: Gender and Collegial Decisionmaking in the Federal Appellate Courts, 114 Yale L.J. 1759 (2005); see also Dermot Feenan, Editorial Introduction: Women and Judging, 17 Feminist Legal Studspa. 1, 4–6 (2009).

[141]. See, e.g., Eden B. King, Michelle R. Hebl & Daniel J. Beal, Conflict and Cooperation in Diverse Workgroups, 65 <J. Soc. Issues 261, 267–68 (2009); Karen A. Jehn, Gregory B. Northcraft & Margaret A. Neale, Why Differences Make a Difference: A Field Study of Diversity, Conflict, and Performance in Workgroups, 44 Admin. Sci. Q. 741, 741–42 (1999). But see Sheen S. Levine, Evan P. Apfelbaum, Mark Bernard, Valerie L. Bartelt, Edward J. Zajac & David Stark, Ethnic Diversity Deflates Price Bubbles, 111 Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. 18524, 18528 (2014) (noting that while friction between decisionmaking members can increase conflict, it can also inspire members to think more deeply and ask better questions).

[142]. See Stephen Gilles, What’s So Great About Lay Judgments?: What’s So Bad About Expertise?, 14 Pace Envtl. L. Rev. 499, 500 (1997) (“Cognitive psychologists have reported that both laypeople and experts often suffer from cognitive biases of various kinds.”).

[143]. See supra notes 138–142 and accompanying text.

[144]. Susan P. Sturm, From Gladiators to Problem-Solvers: Connective Conversations About Women, the Academy, and the Legal Profession, 4 Duke J. Gender L. & Pol’y 119, 123 (1997) (“On a normative level, the desire to bring these conversations together stems from the view that legal education and the legal profession cannot claim legitimate moral stature if they systematically exclude, marginalize, or undervalue women and people of color.”).

[145]. See supra note 20.

[146]. See supra note 20.

[147]. See supra note 20.

[148]. Brown, supra note 48, at vi–vii.

[149]. See id. at ix.

[150]. Id. at 65 (citing Howard Lesnick, The Federal Rule-Making Process: A Time for Re-Examination, 61 A.B.A. J. 579, 581 (1975)).

[151]. Id. at 66.

[152]. Id.

[153]. Id.

[154]. James E. Pfander, The Chief Justice, the Appointment of Interior Officers, and the “Court of Law” Requirement, 107 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1125, 1125, 1132–35 (2013) (assessing the Chief Justice’s power to appoint, among other positions, bureaucratic court positions, court procedural rulemaking committees, and the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation).

[155]. Id. at 1130–32.

[156]. See Stephen B. Burbank & Sean Farhang, Federal Court Rulemaking and Litigation Reform: An< Institutional Approach, 15 Nev. L.J. 1559, 1596 (20<15) (noting that where the Chief Justice is appointed by a president who hails from the party that is also in charge legislatively, there is little or no political will to change the current appointment structure).

[157]. Eli Wald, A Primer on Diversity, Discrimination, and Equality in the Legal Profession or Who is Responsible for Pursuing Diversity and Why, 24 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 1079, 1113 (2011); see also Martinez, supra note 20 (arguing that the legal profession should adopt policies designed to encourage underrepresented groups to share their concerns and experiences).

[158]. Examining the Demographic Compositions of U.S. Circuit and District Courts, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Feb. 13, 2020, 12:01 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/courts/reports/2020/02/13/480112/examining-demographic-compositions-u-s-circuit-district-courts/#:~:text=The%20Federal%20Circuit%20comprises%20judges,percent%20of%20its%20active%20judges [https://perma.cc/4PPJ-W5HE] (looking at sitting circuit court judges). Seventy-seven percent of active federal appellate judges are white and 65.5 percent are male. Id. See also Jason Iuliano & Avery Stewart, The New Diversity Crisis in the Federal Judiciary, 84 Tenn. L. Rev. 247 (2016).