Introduction

This Article builds on an intervention Luke Harris and Uma Narayan made more than two decades ago in the Harvard BlackLetter Law Journal repudiating the conceptualization of affirmative action as a racial preference.1 The central claim we advance is that affirmative action levels the playing field for all African Americans students, not just those who are class-disadvantaged. Developing this argument is crucial against the backdrop of the argument that affirmative action is both over- and underinclusive.

The underinclusive argument posits that affirmative action does little to remedy the extent to which, across the country, African American students are forced to attend failing primary and secondary schools whose pipelines lead to prisons, not universities. The claim is that most students who attend these schools are simply too disadvantaged to benefit from policies that presume college eligibility at a minimum.2 At best, extending affirmative action to disadvantaged black students would create a “mismatch” problem;3 the policy would put black students in educational contexts that are above their intellectual achievement grade. This mismatch would then cause black students to struggle academically to fit in and succeed.

Importantly, proponents of mismatch do not limit their application of the theory to economically disadvantaged blacks. They apply arguments about mismatch to middle-class African Americans as well. Indeed, in the Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (Fisher II)4 litigation, a number of the amicus briefs specifically draw on the mismatch theory to challenge the constitutionality of the University of Texas’s admissions policy.5 Their target in doing so is not blacks who are class-disadvantaged but those who presumptively are not.

Whites, on the other hand, largely escape the mismatch critique. People who argue that affirmative action should focus more on working-class whites, not middle-class blacks, rarely invoke the possibility of mismatch as a concern. The assumption seems to be that, unlike African American beneficiaries of affirmative action, white working-class beneficiaries will not be in over their head.

Cheryl Harris has suggested that the reason arguments about mismatch are almost always rehearsed with reference to African Americans is because the mismatch thesis aligns with preexisting notions of black intellectual deficit.6 Put another way, the theory of mismatch is another way of writing intellectual deficiency and inability into race—and more specifically, blackness.7 Black intellectual inferiority has long been an important part of the social transcript of American life. Indeed, perhaps the only thing easier in the United States, racially speaking, than questioning black intellectual ability is associating African Americans with crime.8 That the mismatch theory at least implicitly relies on longstanding “reasonable doubt” about black intellectual competence and capacity makes it all the more important that scholars and policymakers carefully examine the empirical basis for the theory.9

But that is not our project in this Article. We invoke the theory of mismatch here for a more limited purpose: to reveal how it facilitates the underinclusive argument against affirmative action. This brings us to the overinclusive claim.

The overinclusive critique of affirmative action posits that affirmative action benefits African Americans who are not disadvantaged. Extending this benefit to privileged blacks is unfair, the reasoning goes, particularly because this benefit comes at a cost to poor whites.10 Why should admissions policies systematically prefer privileged students (read: black middle-class applicants) over disadvantaged students (read: poor whites)?11 That is the question the overinclusive argument against affirmative action encourages us to ask—and the answer that question invites is clear: Admissions policies should not prefer privileged black students over disadvantaged white ones.

Like many of the arguments against affirmative action, the over- and underinclusive claims against the policy are not new. Writing in 1994, Harris and Narayan observed that:

This juxtaposition of the middle-class Black against his poor Black counterpart often has the purpose of setting up an insoluble dilemma between whose horns any possible justification for affirmative action seems to disappear. The middle-class Black does not need or ‘deserve’ any help countering the effects of racism; therefore, affirmative action is not warranted with respect to him or her. By contrast, the poor Black perhaps deserves some sort of help, but is situated so as not to be in a position to benefit from affirmative action policies; thus they are of no practical import to him or her.12

The “insoluble dilemma” to which Harris and Narayan refer is another way of saying that opponents of Affirmative action describe African Americans as either too advantaged to deserve affirmative action or too disadvantaged to benefit from the policy. Privileged or mismatched,13 the lose-lose position African Americans occupy in anti-affirmative action discourse places them beyond the remedial reach of the policy.

The remainder of this Article focuses on the privileged side of the “insoluble dilemma.” We do so because, since the publication of Harris and Narayan’s paper more than two decades ago, we have yet to read a full defense of affirmative action that expressly focuses on middle-class black applicants.14 By and large, proponents of affirmative action treat black students whose experiences do not comfortably fit the K-12 educational disadvantage narrative as the unintended but unavoidably necessary beneficiaries of the policy.

One of the most striking manifestations of this necessary evil defense of affirmative action is the notion that supporting affirmative action for middle-class African Americans is like supporting partial-birth abortion; ordinarily, one might not want to support partial-birth abortion, but one does so nevertheless to ensure women’s reproductive rights in general. Similarly, so the argument goes, one ordinarily might not want to support affirmative action, but one does so to ensure racial diversity and to prevent the resegregation of American colleges and universities.15

The failure of proponents of affirmative action to robustly defend the policy for middle-class African Americans strengthens the perception of affirmative action as a racial preference. Put another way, the perception of affirmative as a racial preference has particular traction when its beneficiaries are black but not class-disadvantaged. Think about the matter this way: If people believe that colleges and universities employ affirmative action to admit African Americans who are not economically disadvantaged, the conclusion that affirmative action is a racial preference is easy to reach—black students who are not disadvantaged are getting preferential treatment because of their race. Liberals defend this preference because it advances diversity and contributes to the “robust exchange of ideas.”16 Conservatives reject it because it violates their understanding of colorblindness and effectuates what they call “reverse discrimination” against whites.17

This Article reframes the debate. It does so by explaining why affirmative action for middle-class blacks is neither a racial preference for African Americans nor reverse discrimination against whites. We locate our argument in the context of admissions. Specifically, we identify a number of disadvantages black students—across class—likely experience prior to and in the context of applying to colleges and universities. We argue that these disadvantages can diminish the competitiveness of a black student’s admission file and that affirmative action helps to counteract this negative effect. In advancing this argument, we hope to make clear that racial inequality is not exhausted by class inequality, that affirmative action is not a racial preference but a mechanism to level the admissions playing field, and that the inclusion of middle-class African Americans in affirmative action programs is not an effort to displace working-class or poor blacks but a way of achieving an important and insufficiently acknowledged diversity benefit: namely, intraracial diversity, or diversity among and between black students, including along the class spectrum.18

The remainder of the essay is organized as follows. Part I offers a theoretical argument that explains why it is a mistake to frame affirmative action as a racial preference. We identify a number of obstacles African American students across class likely encounter—up to and including the moment of admission—that potentially negatively impact their formal academic performance and the overall competitiveness of their admissions files. These obstacles create what we call an “admissions imbalance” that affirmative action helps to offset. The failure to correct for this imbalance simultaneously hurts black students and benefits students whose educational trajectories do not include the racial obstacles we will describe. To put this point another way, what black students experience as racial disadvantages, white students experience as a “thumb on the scale,”19 whereby the absence of racial obstacles puts white students at an advantage in the college application process. In this respect, institutions that do not acknowledge and ameliorate the obstacles we outline in Part I end up producing the very thing many attribute to affirmative action: racial preference.

Drawing principally from research in social psychology, Part II employs empirical evidence to support the theoretical claims Part I articulates. Here we demonstrate that several of the disadvantages black students encounter potentially affect traditional academic performance indicators (such as standardized test scores and grade point averages (GPAs)) and other critical dimensions of an admission file.

Against the backdrop of Parts I and II, one might reasonably ask why academics, policymakers, lawyers, and judges continue to frame affirmative action as a racial preference. That is the question we take up in the conclusion. We suggest that part of the reason people have difficulty seeing affirmative action as a mechanism that levels the playing field for African Americans across class is because the debate over affirmative action overstates or flattens the middle-class status of African Americans. Indeed, in at least some of the anti-affirmative action discourses, opponents of the policy treat middle-class African American youth as being, effectively, as privileged as the children of President Obama.

I. Blacks Who Are Not Class-Disadvantaged Are Truly Disadvantaged: The Theoretical Argument

Although racial diversity, not racial disadvantage, counts as a compelling state interest for affirmative action,20 public support for the policy turns, at least in part, on whether people perceive its beneficiaries to be disadvantaged.21 In advancing this claim, we do not mean to suggest that diversity and disadvantage are oppositional concepts or that they are necessarily in tension with each other. Our point is rather that, as a formal doctrinal matter, equal protection doctrine requires that colleges and universities ground their defense of affirmative action on a diversity, not a disadvantage, rationale.22

Yet it is clear that for at least some Justices on the U.S. Supreme Court, concerns about disadvantage shape how they think about the constitutionality of affirmative action. One of the clearest examples of this is manifested in the Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (Fisher I) litigation,23 in which Abigail Fisher sued the University of Texas, alleging that the school’s affirmative action plan violated her rights to equal protection under the U.S. Constitution. During oral argument, Justice Alito pressed Gregory G. Garre, the attorney representing the university, on what Justice Alito perceived to be a fundamental problem with how the school was administering its affirmative action plan:

Mr. Garre: And I don’t think it’s been seriously disputed in this—this case to this point that, although the percentage plan certainly helps with minority admissions, by and large, the—the minorities who are admitted tend to come from segregated, racially-identifiable schools.

Justice Alito: Well, I thought the whole purpose of affirmative action was to help students who come from underprivileged backgrounds, but you make a very different argument that I don’t think I’ve ever seen before.

The top 10 percent plan admits lots of African Americans—lots of Hispanics and a fair number of African Americans. But you say, well, it’s—it’s faulty because it doesn’t admit enough African Americans and Hispanics who come from privileged backgrounds. And you specifically have the example of the child of successful professionals in Dallas.

Now, that’s your—that’s your argument. If you . . . have an applicant whose parents are—let’s say they’re—one of them is a partner in a law firm in Texas, another one is a . . . corporate lawyer. They have income that puts them in the top 1 percent of earners in the country, and they have—parents both have graduate degrees.

They deserve a leg-up against, let’s say, an Asian or a white applicant whose parents are absolutely average in terms of education and income?

Mr. Garre: No, Your Honor . . . .

Justice Alito: Well, how can the answer to that question be no, because being an African American or being a Hispanic is a plus factor.24

While there is much that one might say about the foregoing exchange, two points in particular deserve engagement. First, Justice Alito is clearly invoking a version of the black son of a lawyer/white son of a coal miner trope. More specifically, he is contesting the legitimacy of an admissions regime under which “African Americans and Hispanics who come from privileged backgrounds” get a “leg-up against, let’s say, an Asian or a white applicant whose parents are absolutely average in terms of education and income.”

Second, Justice Alito makes clear that, from his perspective, “the whole purpose of affirmative action was to help students who come from underprivileged backgrounds.” One might conclude from this statement, particularly because a Supreme Court Justice articulates it, that a university can defend its affirmative action policy on the ground that it benefits students from “underprivileged backgrounds.” One would be wrong to make this conclusion. As we have already stated and want to repeat here, diversity, not underprivileged backgrounds, serves as compelling justification for affirmative action. That is to say, under current law, diversity “is the whole purpose of affirmative action.”25

If equal protection law is clear regarding the constitutional basis on which universities can defend their affirmative action policy, why would Justice Alito get the remedial justification for the policy so wrong? The answer, we think, is that like many other people, Justice Alito believes that affirmative action should correct for or counteract the disadvantages people encounter in life, notwithstanding that diversity, and not disadvantage, is the constitutionally legitimate justification for affirmative action.

From Justice Alito’s perspective, the black son of a lawyer is not, to borrow from William Julius Wilson, “truly disadvantaged.”26 The black son of a lawyer son should not, therefore, be a beneficiary of affirmative action.

Justice Alito’s sense that blacks who are not class-disadvantaged are not disadvantaged at all likely shapes his perception of affirmative action as a “leg-up.” Indeed, further along in the oral argument, Justice Alito expressly connects his concerns about blacks who are not class-disadvantaged with his conception of affirmative action as a racial preference. He does so in the following question he directed at the Solicitor General, Donald Verrilli: “Does the United States agree with Mr. Garre that African American and Hispanic applicants from privileged backgrounds deserve a preference?”27 The very framing of Justice Alito’s question reveals not only his insinuation that middle-class blacks are not disadvantaged, but also his conceptualization of affirmative action as a racial preference. The short of it is that Justice Alito’s engagement with both Verilli and Garre reflects the view that because the University of Texas’s admission policy confers a racial preference to students who are not disadvantaged (middle-class blacks), the policy, at the very least, is constitutionally suspect.

In this Part we demonstrate why Justice Alito’s framing of affirmative action is flawed. We do so by interrogating the dominant metaphor people across the ideological spectrum have employed to describe affirmative action—that it is “a thumb on the scale.” We present six schematics to show how the thumb on the scale characterization of affirmative action simultaneously obscures black disadvantages and facilitates the affirmative action-as-preference frame.

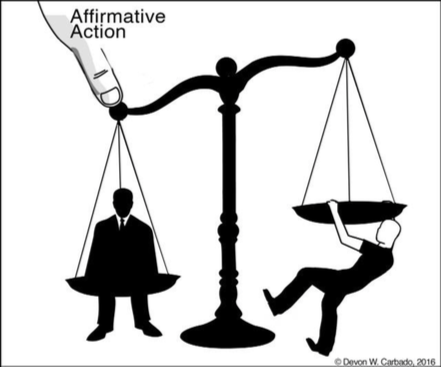

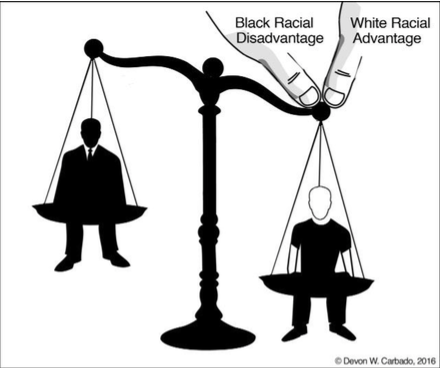

We begin with the first schematic, Figure 1:

Figure 1

Figure 1 presents the default admissions regime in the form of a scale. A black person sits on one side of the scale and a white person sits on the other. A critical feature of this scale is that it is perfectly leveled. The black body weighs no more than the white body. The black applicant and the white applicant are in equipoise.

Moreover, the black person and the white person look exactly the same. The only difference between the two is that one has a black face and the other’s face is white. Race, under this view, marks neither disadvantage nor privilege. It is nothing more than skin color. This decidedly thin conception of race invites us to conclude that, in the context of admissions, race does not—and should not—matter.28

In sum, Figure 1’s perfectly balanced scales and similarly situated representation of the black and white applicants communicate the idea that the admissions process is colorblind and is one in which applicants are treated perfectly equally. Under the admission system that Figure 1 depicts, neither the white applicant nor the black applicant is favored. Nor is either one disadvantaged. The admissions process Figure 1 depicts is balanced, racially neutral, and fair.

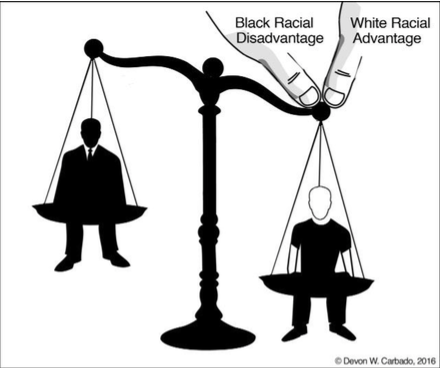

Now consider Figure 2:

Figure 2

Figure 2 depicts a perception of how affirmative action changes the picture of neutrality that Figure 1 presents. Appearing in the form of a thumb, affirmative action creates an imbalance. The weight of the thumb tips the scales in favor of the African American applicant.

Figure 2 illustrates two additional asymmetries that help to shore up the perception of affirmative action as a preference. First, the black applicant is doing nothing to achieve the competitive advantage he enjoys. It is not, in other words, an advantage he earned. He is in the favorable admissions position Figure 2 presents (the scales tilt in his favor) because of the preference affirmative action accords to him simply based on his race. The white applicant, meanwhile, struggles mightily to pull the scales down to its original—and presumptively racially neutral—position. But no matter how hard he works, the scales remain tipped in favor of the black applicant. The weight of the so-called “black bonus” of affirmative action is too heavy for the white applicant to counteract.29

Second, the black applicant is not the “underprivileged” black person who, for Justice Alito, is the appropriate beneficiary of affirmative action. Professionally dressed, the black applicant stands in for those privileged and undeserving black beneficiaries of affirmative action whom opponents of affirmative action regularly conjure up. The white applicant, on the other hand, is more casually dressed, suggesting a working-class or poor-white identity. With respect to economic resources, this applicant is, at best, the white person who, in Justice Alito’s account, affirmative action disadvantages—a white applicant who comes from a family that is “absolutely average in terms of education and income”—and at worst, economically far below that average. In short, under Figure 2, the admissions system prefers the black applicant (who is presumptively privileged and exerting no effort) over the white applicant (who is presumptively disadvantaged and hard-working). Here, the admissions process is unbalanced, racially biased, and unfair. It represents an instance of “reverse discrimination.”30

It is Figure 2 that opponents of affirmative action have in mind when they ask: Why should an admissions policy extend a preference to the black child of a lawyer but not the white child of coal miner?31 When asked, this question is not necessarily about facilitating the upward mobility of the coal miner’s child.32 It is often about criticizing affirmative action as a policy that focuses on race, not disadvantage.33

Importantly, both liberals and conservatives acquiesce in the image of affirmative action Figure 2 depicts. Both conservatives and liberals regularly refer to affirmative action as a thumb on the scale and both conceptualize the policy as a preference.34 As noted earlier, the basic difference between conservative and liberal positions on affirmative action is that whereas liberals believe that the costs of affirmative action are outweighed by the benefits (including diversity), conservatives perceive the costs of the policy (including “reverse discrimination”) to be too high.

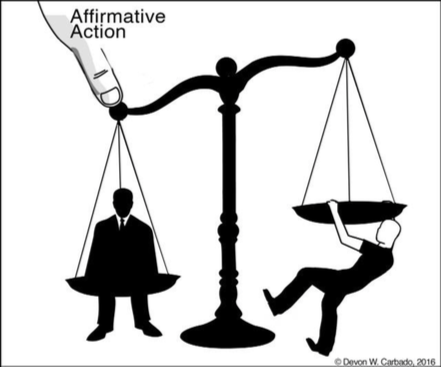

Consider now Figure 3:

Figure 3

Like Figure 2, Figure 3 depicts an admissions regime that is not level. Here, too, the scales are uneven. But this time, they tip in favor of the white applicant. Without further explanation, and against the well-established backdrop of (1) stereotypes about the poor work ethic and intellectual deficit of African Americans,35 (2) discourses about the achievement gap between black and white students,36 (3) the assumption that whites do not benefit from affirmative action,37 and (4) the unlikeliness that any institution would intentionally discriminate in favor of white applicants or against black applicants,38 the conclusion one might draw from Figure 3 is twofold. First, the white applicant deserves to be in the competitive position he enjoys; and second, the black applicant deserves to be at a disadvantage. Figure 3, in other words, represents what some might call a “racially natural disequilibrium,” one that derives from the “natural” fact that the white applicant is smarter and/or has worked harder than the black applicant. Under this view, merit explains why the black applicant is disadvantaged and the white applicant is advantaged. No remedial intervention is therefore necessary. What is needed is what Dinesh D’Souza would call a “cultural reconstruction.”39 Black parents, community leaders, and political figures should change the cultural habits of black teenagers,40 encourage them to study hard and stay in school, and persuade them to not associate the pursuit of academics with “acting white.”41 Hard work, greater effort, and a stronger commitment to education on the part of black students would tip the scales in their favor, make them more competitive, and remove the asymmetry Figure 3 illustrates. The solution for the imbalance Figure 3 presents, in sum, is for black students to fix themselves and become, like Asian Americans, a “model minority.”42

Figure 4 contextualizes the imbalance Figure 3 presents. It puts into focus two ways in which race tilts the scales in favor of whites, both of which are invisible in Figure 3:

Figure 4

Under Figure 4 (and unlike Figure 3), the asymmetry in the picture is not a function of merit.43 The white applicant is advantaged not because he is smarter or works harder than the black applicant. The white applicant benefits from two thumbs on the scale: (1) the thumb of black racial disadvantage (the disadvantages that black—but not white—applicants experience), and (2) the thumb of white racial advantage (the advantages that white—but not black—applicants experience). We discuss them in turn.

The black disadvantage thumb is shorthand for a number of structural racial disadvantages black applicants bring to or experience in the context of the admissions process. We discuss these disadvantages more fully in Part II and provide a summary articulation of some of them below:

- Deficient Standardized Tests (the extent to which standardized tests have a disparate impact on African Americans and do not accurately assess their abilities);

- Explicit racial biases (consciously held negative views about a group);

- Implicit racial biases (unconsciously held negative views about a group);

- Stereotype threat (the perception that one’s performance in a particular domain will confirm negative stereotypes about one’s group);

- Racial isolation (the sense of alienation and marginalization that derives from the underrepresentation of one’s group within a particular institutional setting);

- Negative institutional cultures (environments whose norms and practices render some groups insiders and others outsiders).

Because the foregoing factors put blacks as a group, relative to whites as a group, at a competitive disadvantage, we might think of these factors, cumulatively, as constituting a thumb on the scale for whites.

Given our earlier observations about race and class, we should be clear to note that the racial disadvantages we set forth above are not class-dependent. Conspicuously absent from our list is K–12 segregation and inequality.44 We excluded that factor to avoid getting bogged down in a debate about whether K–12 inequality is a class-based problem or a racial one (we think it is both). Instead, we focus on a set of factors whose impact unequivocally transcends class and refer to them, cumulatively, as the black racial disadvantage thumb.

Think now about the white racial advantage thumb. Two advantages, together, might be thought of as a thumb on the scale. First, white applicants benefit from what we call the “intergenerational value of whiteness.” Every white person benefits from the intergenerational value of whiteness. Our argument here is not principally about the fact that some whites have been able to transfer resources and wealth (including cultural capital) across generations in ways that African Americans generally have not. If our claim about white advantage centered on transfer of resources and wealth, many whites—including the son of a coal miner previously discussed—would be excluded from the benefits we attribute to whiteness. Our argument about white advantage is grounded by the observation that to be white in the United States (irrespective of one’s genealogical relationship to slavery or Jim Crow) is necessarily to inherit the historical badge of honor, privilege, respectability and positive social meanings associated with whiteness and white people.45 While class mediates the degree to which whites benefit from this advantage,46 the phenomenon transcends class.

The second white advantage Figure 4 means to capture is in-group favoritism. Racial inequality is not just a function of out-group derogation and exclusion, but also preferential treatment toward the in-group. Although positive in-group bias and negative out-group bias are often discussed as two sides of the same coin, research shows that in-group favoritism and out-group prejudice are in fact distinct.47 Though each operates to maintain systems of inequality, discrimination can be motivated by in-group favoritism alone, without any negative intent or hostility toward the out-group, and vice versa.48 In-group favoritism is ubiquitous, but has the greatest effect when in-group members are in positions of power and can thus preferentially bestow a range of benefits, access to resources, and opportunities to other in-group members. Because of the political and economic power whites have (and historically have had) as a group, whites are more likely to benefit from in-group favoritism than any other racial group, including African Americans. Researchers have proposed that in-group favoritism plays a key role in the differential advantage of whites in a large swath of life, from general helping behavior,49 to tipping,50 to evaluation of employment, and housing applications and interviews.51 The cumulative advantages that can accrue from being the repeat beneficiary of in-group preferences are likely significant.

To sum up, under Figure 4, the default admissions regime is uneven. The scales are unbalanced. Two thumbs on the scale tip the process in favor of whites to the disadvantage of African Americans.

Figure 5 reintroduces the thumb of affirmative action into the analysis:

Figure 5

In this image, affirmative action is a part of the picture but it does not create the imbalance. Indeed, even with the thumb of affirmative action, the scales are still uneven. They continue to lean in a direction that disadvantages African Americans. The combined weight of the black racial disadvantage thumb and the white racial advantage thumb exceeds that of the affirmative action thumb. Under Figure 5, while affirmative action is ameliorative, the policy does not completely counteract the combined effects of white advantage and black disadvantage.

At this point in the analysis, an important caveat is in order: Notwithstanding the very specific narrative Figure 5 invites, we should be clear to state that we do not present Figure 5 as a strong empirical claim. It is hard to know, for example, whether, with the thumb of affirmative action back on the scales, the scales remain tilted in favor of whites. In some instances, the effect of affirmative action might be to level out the scales; in other instances, the policy might have an overcorrection effect, tilting the scales in favor of African Americans. To put the point as Harris and Narayan might, we are not arguing that “affirmative action policies are, or can be, magical formulas that help us determine with perfect precision in every case the exact weights that must be accorded a person’s class background, gender, and minority status, so as to afford him or her perfect equality of opportunity.”52 Because context will surely matter, the specific picture Figure 5 paints is best viewed as a soft default. The more important takeaway from Figure 5 is that affirmative action does not disrupt an otherwise racially neutral baseline at which applicants are similarly situated. The policy attempts to correct for the thumbs of black racial disadvantage and white racial advantage, both of which tilt the admissions scales in favor of white applicants.

This brings us back to Figure 2, the representation of affirmative action as a racial preference. The image, again, is this:

Figure 2

Part of what this image communicates is that, but for affirmative action, the white applicant would be in a more competitive position than he currently occupies. A stronger version of this argument frames affirmative action as an admissions barrier for whites. More precisely, the claim is that affirmative action causes admissions officers to deny admissions to white students those officers would otherwise admit.

That argument is more spin than empiricism. Indeed, as Kimberly West-Faulcon has argued, drawing on the work of Goodwin Liu, there is “causation fallacy” in the argument that asserts that but for affirmative action the University of Texas would have admitted Abigail Fisher. As West-Faulcon explains, there are simply too few black students in the admissions pool of elite colleges and universities for affirmative action to have the causation effect Abigail Fisher and others attribute to it.53

In some ways, even the figures we employ to challenge the racial preference framing of affirmative action invite the “causation fallacy” argument in that they paint a picture of affirmative action in which—throughout the admissions process—a white student finds himself in contestation with a black student over a particular admissions spot. We know of no school that would describe its admissions process in that way. Most, if not all, schools would say that they employ some version of “holistic review” under which admissions decisions resemble something like a totality of the circumstances analysis. Of course, standardized test scores and GPA typically weigh more heavily than other variables. The point is that while most elite colleges and universities employ affirmative action in the context of admissions, they do not therefore necessarily have affirmative action slots per se.

Second, even if a school aspired to conduct its admissions process so that each spot was a tournament between a white student and a black student, it simply could not do so. Given, as we have said, the relatively small number of African Americans in the applicant pool of elite colleges and universities, and the fact that not all black applicants are beneficiaries of affirmative action, it is hard to see how there could ever be an admissions system in which every white student finds himself in competition with a black beneficiary of affirmative action for a particular admissions spot.

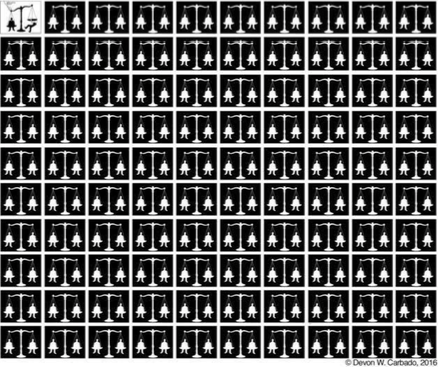

Significantly, a relatively recent study on race and admissions describes the effect of affirmative action on white applicants as negligible.54 Focusing specifically on Harvard University, the study concludes that removing all African Americans and Latinos from the admissions process at Harvard would increase the likelihood of white applicants being admitted by only 1 percent.55 Assuming, arguendo, that admissions regimes include tournaments between black and white applicants and that affirmative action is a racial preference—this study indicates that the worst-case scenario for white applicants looks something like Figure 6:

Figure 6

In only one of the hundred admissions scales—the first one in the upper-left corner—is a white student in a tournament with a black applicant who is benefitting from the affirmative action thumb on the scale. The remaining ninety-nine scales do not involve blacks, Latinos, or affirmative action.56

To repeat: We do not think that admissions systems operate as white vs. black tournaments; we do not believe that affirmative action is a racial preference; and it is not our view that, if one thinks of admissions processes as scales, the scales are otherwise balanced but for affirmative action. We employ Figure 6 not to acquiesce in any of the foregoing ideas but to visually contextualize the strongest case against affirmative action. In context, that case, as Figure 6 suggests, is decidedly weak.

* * *

Central to our thesis thus far is the claim that affirmative action is not a racial preference because, among other things, it corrects for a number of disadvantages African Americans experience up to and during the admissions process. The question now is whether we can support that thesis empirically. Is there evidence, in other words, to support our contention that African Americans across class are vulnerable to the racial disadvantages this Part discussed—and evidence linking those disadvantages to critical aspects of an admissions file? The short answer to both questions is “yes.” Part II elaborates on these questions—and their answers.

II. Quantifying Black Racial Disadvantage: The Empirical Evidence

This Part provides empirical evidence to support our claim that black students across class, and not just class-disadvantaged black students, experience multiple disadvantages that likely affect their academic performance and the overall competitiveness of their admissions files. As a starting point, we ask you to consider the following scenario.

Imagine that the son of a black lawyer starts his first day at a predominantly white high school. What concerns and anxieties does his parent have as she waves goodbye to her teenager? Some concerns—whether her child will eat lunch at the appropriate time (if at all) or will spend too much time on social media—are universal parenthood worries. But beyond these concerns, the black parent will have a number of very specific worries. The black parent will wonder whether her son made it safely to school without being mistakenly profiled as a criminal suspect—and whether at school so-called Resource Officers (local police officers assigned to work at the school) will intentionally profile him as a criminal suspect. She will wonder whether the teachers understand that educators hold lower expectations (both consciously and unconsciously) of black students. She will ask herself whether this will be another year in which teachers patronize her child, offer less constructive feedback on his work, and provide few, if any, mentorship opportunities. The black parent will also hope that her advice to her son “not to argue with the teachers and do exactly as they tell you” will prevent teachers from perceiving him as “a boy with an attitude.”

The black parent will wonder whether this year her son will be cajoled—again—into giving the annual Black History Month speech, pressured into joining the basketball team (though he would rather play tennis), and tokenized and marginalized as the holder of the most insignificant position in student government. The black parent will also think about the racial demographics of the school in a broader institutional sense. Will her son, finally, have a black teacher? A teacher of color? Will there be a few more black students at the school this year? (She knows there will not be many more than the last time she researched the matter.) Will some of the black students at the school be in her son’s class so that he feels some measure of racial comfort—or will her son have to supply racial comfort to his classmates to make them feel less anxious and nervous around him?57

Will her son be tracked into the less demanding classes? Will he be counseled out of thinking about competitive colleges and universities as a future possibility? Will any of her son’s teachers evidence a concern about and be attentive to his overall racial well-being?

The black parent’s concerns put into sharp relief some of the racial obstacles her son will face throughout his high school career, notwithstanding that he is middle-class. This Part explains how these obstacles can have a negative effect on the admissions file of this student five years downstream, shaping not only “hard” evaluative measures, such as standardized test scores and grades, but also “soft” evaluative measures, such as leadership experience, awards, extracurricular opportunities, internships, and letters of recommendations. We focus our attention on four specific racial disadvantages—stereotype threat, implicit biases, explicit biases, and negative institutional culture—and show that they are independent of economic class status.

A. Stereotype Threat

Stereotype threat is one of the most studied, and most prevalent, forms of psychological strain faced by black students.58 This Subpart explains how stereotypes can negatively affect a black student’s performance on standardized tests, classroom engagement, and whether and to what extent the student seeks help outside of the classroom or visits a teacher during office hours.59 Each of the foregoing effects potentially diminishes the competitiveness of a student’s admissions file.

Roughly, stereotype threat refers to a scenario in which (a) because of one’s membership in a particular social group, negative stereotypes exist about one’s ability to perform in some specific domain, (b) one is consciously or unconsciously concerned about confirming those stereotypes, and (c) that concern undermines the quality of one’s performance. For example, pervasive stereotypes that blacks are less intelligent or less capable60 may cause black students to fear that their performance in school will confirm, to themselves or to others,61 that these negative stereotypes are true. These worries raise the stakes of school performance, adding an additional layer of pressure to achieve that increases stress,62 undermines learning and engagement,63 taxes cognitive resources,64 and impairs academic performance.65

The effect of stereotype threat on black students has been observed in hundreds of psychological studies employing rigorous experimental methods, both in controlled laboratories and in the field.66 For example, an early laboratory experiment conducted by Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson randomly assigned black and white participants to complete verbal questions from the graduate record examinations (GRE) under one of two conditions: threat or no threat.67 In the threat condition, participants were told that the questions were a test that would measure their intellectual ability, a statement that for black students activates known racial stereotypes about intellectual inferiority and triggers the concern that they may confirm this negative stereotype by performing poorly. In the no threat condition, participants were told that the questions were simply a laboratory problem-solving task that would not evaluate their ability. The authors found that black students performed significantly worse than white students in the threat condition, but equivalent to white students in the lower-stakes no threat condition. In other words, when racial stereotypes of intellectual inferiority were made salient—simply by stating that the test was diagnostic of intellectual ability—black students faced the psychological strain of stereotype threat, which disrupted their performance and produced a racial performance gap; in contrast, when the questions were framed as nonevaluative (which is very rarely how tests are presented in the real world), the racial performance gap disappeared.

This finding has been replicated many times, not just in the laboratory, but also in real-world settings. For example, California administers two sets of exams with similar content but different psychological effects, closely mirroring the threat and no threat conditions outlined above. The state-mandated high school exit exam represents a high-stakes testing environment (threat) that students must pass to graduate from high school, whereas state achievement exams are low-stakes because students’ performance on these tests does not affect their ability to graduate, grades, or other academic outcomes (no threat). In a study of these exams, Sean Reardon and colleagues found that black and Latino students tended to perform just as well as white students on the low-stakes achievement exams, but significantly worse on the high-stakes exit exams.68

The effects of stereotype threat have also been documented experimentally many times through randomized controlled trials, where half of students were assigned to participate in brief exercises designed to reduce stereotype threat.69 By administering these exercises at the outset, psychologists have directly measured the effect of stereotype threat on black students’ academic achievement by observing what happens when this psychological strain is mitigated as a factor.

Meta-analyses70 examining the performance of the thousands of students who have participated in stereotype threat-reduction field experiments over the past decade estimate that the difference between academic achievement when stereotype threat has been experimentally reduced versus when the psychological environment has been left in its natural state is the equivalent of about a sixty-three point difference on the SAT.71 In fact, these meta-analyses find that, after threat is reduced, students contending with negative stereotypes about their performance (black students) actually outperform their non-stereotyped peers (white students).72 These results show the clear depressive effect of stereotype threat on black students’ academic performance; indeed, instead of reflecting academic ability, test scores and grades often reflect the presence of race-related psychological threat in students’ environment. Does a sixty-three point difference on the SAT matter? In the highly competitive world of college admissions, every point matters.

Importantly, this process of stereotype threat is not unique to black students; rather, it is a normal and ubiquitous response to an environment where negative stereotypes and bias about any group loom large. For example, awareness of the stereotype that older adults have problems with memory can cause older individuals to perform worse on memory tasks when the tasks are framed as diagnostic of memory capacity.73 After activation of stereotypes that women are worse than men at math74 and driving,75 women underperform compared to men on math and driving tests, whereas no gender differences are observed when these stereotypes are not made salient. Similarly, when an athletic task is framed as a test of natural athletic ability, white men perform worse than black men;76 when white men think that they are being compared in math ability to Asian men, their performance on math tests declines.77 Stereotype threat results in the greatest performance deficits for those who identify most with the threatened group identity (for instance, their race) and the domain in which they are stereotyped (for example, school performance),78 but can affect members of any group that is negatively stereotyped, regardless of whether they believe that the stereotype is true.

In the extensive body of research on race-based stereotype threat (or any other kind of stereotype threat), there is no empirical nor theoretical evidence that relative economic advantage shields black students from the effects of racial stereotype threat. A black student who is economically advantaged is aware of and contends with negative racial stereotypes of intellectual ability and therefore is just as susceptible as a black student who is economically disadvantaged to the harmful effects of stereotype threat due to his or her race.

In fact, to the extent that economically advantaged black students are participating in activities associated with higher socioeconomic status of which blacks have not typically been a part (including ballet, playing the violin, and attending private schools), these students might experience more stereotype threat. Research shows that context cues, such as a small number of ingroup members present, low minority representation in brochure photographs, and even physical objects typically associated with the dominant, non-stereotyped group can trigger stereotype threat.79 Based on this work, middle-class blacks who tend to have more exposure to mostly-white environments than economically disadvantaged blacks may face more consistent and stronger effects of stereotype threat because they contend with greater exposure to such cues. There is some evidence to support this proposition. Something as simple as taking an exam in a mostly white classroom can depress black students’ scores more than taking the identical exam in a room with a higher concentration of same-race students.80

The effects of stereotype threat go beyond performance suppression. Stereotype threat can negatively affect classroom learning, prevent ability building, and undermine academic engagement.81 For example, because of stereotype threat, black students may be reluctant to join study groups, ask questions in class, or visit professors’ office hours. Avoiding each of the preceding interactions reduces the risk that the black students will say or do something that will confirm negative stereotypes of their intelligence or competence.82 In this respect, stereotype threat is best understood as a “double jeopardy” phenomenon, affecting not only the back-end educational dynamics (performance on tests) but front-end dynamics as well (classroom learning and study groups).83

Note that the stereotype threat dynamics we have discussed could have an interactive effect in ways that compound the black student’s level of disadvantage. For example, the teacher may assume that the black student who is not speaking in class did not do the assignment or, if he did, must not have understood what he read. She may assume, further, that the black student did not seek guidance because that student is lazy, unmotivated, or disinterested in his future career. Her default with respect to why the student neither speaks in class nor visits her during office hours is unlikely to be that stereotype threat (or some other racial phenomenon, for example, racial alienation or isolation) is playing a role. The problem here, then, is not only that the teacher is unlikely to intervene to diminish the effect of stereotype threat. It is also that her reaction to the student, based on racial stereotypes (for example, that the student is lazy or unmotivated), could potentially heighten stereotype threat for the student, further decreasing the likelihood that the student will participate in class or visit the teacher during office hours.

Significantly, the consequences of this stereotype threat do not end here. The teacher in our hypothetical is unlikely to write a positive letter of recommendation for the student. The fact that the student will not have visited her during office hours and does not speak in class means that the teacher will have to rely on the very thing that is most negatively affected by stereotype threat—the student’s formal academic performance.

B. Implicit and Explicit Biases

While explicit and implicit biases are very different social phenomena, both can have a negative effect on admissions-relevant aspects of a student’s educational experience. Specifically, both forms of biases can negatively affect (1) a teacher’s substantive evaluation of a student’s written work; (2) the level of enthusiasm a teacher expresses in letters of recommendation; (3) teachers’ and administrators’ facilitation of internships and other educational opportunities (such as conferences); (4) teachers’ and administrators’ recommendations for awards; and (5) a student’s leadership opportunities. We begin with a discussion of explicit biases.

1. Explicit Biases

Explicit biases refer to biases about which we are consciously aware. They can take the form of stereotypes (such as, “black people are lazy”)84 or attitudes (such as, “I dislike black people”).85 For example, in 2008, 48 percent of Americans surveyed reported explicit negative attitudes towards blacks.86 By 2013, that statistic increased to 51 percent. Stereotypes and attitudes do not always travel in the same normative direction. One might like African Americans (a positive attitude) but think they are lazy (a negative stereotype); one might dislike Asian Americans (a negative attitude) but think they are smart (a positive stereotype).

Nowadays, explicit bias is seldom stated as directly as our previous examples may imply. In other words, people will rarely say “black people are lazy” or “I dislike black people.” Instead, explicit bias is often more surreptitiously conveyed under the cover of what social psychologists call symbolic racism. Central to symbolic racism is the view that people who are consciously racist will often avoid speaking in terms that reveal their racial views.87 In lieu of using language that directly implicates race, these individuals often employ formally race-neutral language that masks underlying antiblack attitudes or stereotypes regarding African Americans.

According to the theory of symbolic racism, white Americans’ puzzlement over the persistence of racial disparities despite an apparent end to de jure discrimination during the civil rights era88 facilitated the development of a rhetoric that attributed black racial inequality to deficiencies in black American values and culture. In other words, under the belief system of symbolic racism, racial discrimination is no longer a barrier to blacks in education, employment, and other contexts. To the extent that blacks are underrepresented at elite colleges and universities, and overrepresented in prisons, the problem is not bad laws or governance practices but bad individual behavior or culture.89 Because symbolic racism eschews the biological racial inferiority rhetoric of the Jim Crow era, and because it harnesses socially endorsed, traditional American values such as individualism, self-reliance, and hard work, the explanation it offers for ongoing racial disparities is not obviously in tension with civil rights norms of racial egalitarianism.90 Symbolic racism thus captures a phenomenon in which one can argue against various forms of racial remediation, including affirmative action, using traditional American principles and values.91 The invocation of these values provides a kind of rhetorical cover for people’s residual antiblack affect.92

Following its introduction in the mid-1980s, symbolic racism quickly emerged as a powerful predictor of policy attitudes regarding racialized issues such as affirmative action93 as well as voter preference in elections of black candidates.94 More importantly for our purposes, a broad set of studies has shown that symbolic racism is rooted in antiblack animosity. For example, in a study by P. J. Henry and David Sears examining the validity of the phenomenon, symbolic racism was assessed in five survey samples alongside measures of political party identification and ideology, of racial affect (whether, for example, people express warmth to African Americans and claim to like them), and of traditional black stereotype endorsement (for example, the belief that blacks are less intellectually able).95 Using factor analyses, a statistical method designed to identify the variables to which a particular phenomenon like symbolic racism relates, the authors found that symbolic racism mapped equally onto racial animosity (in other words, traditional prejudice and antiblack affect) and conservative political predisposition (in other words, conservative ideology and conservative Republican party identification). Interestingly, the researchers found that racial animosity and political predispositions were not strongly correlated with one another, leading them to conclude that “[t]he symbolic racism belief system is the glue that joins these two elements.”96

Although symbolic racism is rooted in residual antiblack animosity, it is demonstrably distinct. Two indications of this are that more whites support symbolic racism than old-fashioned racism, and symbolic racism has a greater effect on race-related policy outcomes than old-fashioned racism.97

To be clear: We are not saying everyone who opposes affirmative action or other forms of civil rights-oriented policy interventions is racist, symbolically or otherwise. Our suggestion is decidedly more modest—that people who are consciously and intentionally racist typically will not express themselves in ways that betray their racial commitments. Instead, they will employ race-neutral language that aligns with traditional American values or otherwise conceals their biases. The phenomenon of symbolic racism, in short, provides at least some empirical support for the proposition that intentional and explicit biases are not a thing of the past.

Self-reports by blacks provide further support for the argument that explicit bias shapes the experience of African Americans. If hundreds of studies show that blacks report experiencing a particular social phenomenon, our collective default should be to take those reports seriously, including reports of racism. Research reveals that, across age, gender, and class, blacks consistently report more experiences of unfair treatment and discrimination than whites.98 In one large-scale national survey, researchers found that nearly 49 percent of blacks reported encountering some form of discrimination (for example, not given a promotion, hassled by police, denied/received inferior service) in their lifetime.99 Of these respondents, the vast majority (89.7 percent) reported race as a reason for this discrimination.

Findings of the foregoing sort apply to black students as well. One study, for example, corroborated black students’ self-reports of explicit racial discrimination by conducting field observations of the daily interactions among students, teachers, and administrators, along with interviews of students and their families. More precisely, the study included an ethnographic examination of a collection of middle-class black male students at a suburban high school.100 These students and their families reported multiple experiences with racial profiling, stereotypes, and differential treatment based on race. Moreover, the researcher observed repeated differential treatment in discipline, assumptions made by teachers and administrators about the deviance and lack of intelligence of black students, and frequent racist discourse about black students’ performance.101 A particularly significant finding in the study is that “class privilege could not shield [the middle-class black students] from” the foregoing experiences. Indeed, students across class often experienced the institutional culture of the school as a “racial ‘witch-hunt.’”102

Scholarship on graduate students similarly reveals robust self-reports of racism.103 One study engaged seventy-four black doctoral and graduate students from over seventy U.S. colleges and universities. The researchers measured students’ experiences of discrimination (as recorded in student diaries) every day for fourteen days. They found that black students reported experiencing racial discrimination approximately every 3.5 days on university campuses. Furthermore, blacks who reported racial discrimination were also likely to report anxiety, feelings of negativity, and depression. There was no indication in the study that middle-class status inoculated black students from the foregoing experiences.

A final context in which to analyze black students’ self-reports of racism is undergraduate education. Recall the wave of student protest across the country this past year. Black students employed this protest to highlight their sense of isolation and alienation at predominantly white colleges and universities.104 By the end of the calendar year, African Americans at Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Columbia, Indiana University, University of Missouri, and many other schools (ranging widely in tuition cost and admissions requirements) littered the media with reports of subtle and blatant forms racism. Focusing specifically on the University of Missouri, the Huffington Post ran an editorial entitled, “It shouldn’t be so hard to accept that racism is a problem at Mizzou.”105 The article chronicled some of the racist acts faced by black college students at the University of Missouri, including these.

- On the morning of 26, 2010, in the final days of Black History Month, students woke up to find cotton balls spread across the grounds in front of the Black Culture Center on campus—a scene evoking slavery.

- A year after the cotton ball incident, also during Black History Month, a racist slur was spray-painted on a statue outside a

- On the night of 5, 2015, members of the Legion of Black Collegians, a historic black student government group, were rehearsing for a homecoming performance on stage. Some members had a heated exchange with what they later described as an “obviously intoxicated” young white male who interrupted their rehearsal to question why they were there. When he stumbled off the stage and fell he was heard saying into his cellphone: “These n****rs are getting aggressive with me.”

The New York Times published a similar list that included instances of racial profiling by campus police officers, offensive Halloween costumes, racial slurs in school newspapers and classroom discussions, and theme parties at which students appear in blackface and wear modes of dress and makeup stereotypically associated with African Americans. This list likely includes only the most public and unequivocal manifestations of racist conduct, not the entire universe of such events.106 The above examples, and our broader discussion of black self-reports of racism, suggest that it is a mistake to think that explicit racial bias on college campuses is a thing of the past.107

Still, we have not linked our discussion of explicit biases to the domain of student experiences with which we began: admissions-relevant student experiences. In other words, we have not pointed to a moment in which a particular teacher in a particular institutional setting evaluated a particular student negatively because of that student’s race. But because very few teachers are likely to announce their racism, the absence of that empirical showing should hardly surprise us. This bring us to the implicit bias literature. That body of work provides an evidence-based way of linking racial bias to teachers’ and admissions officers’ evaluation of students.

2. Implicit Biases

Implicit bias refers to the attitudes and/or stereotypes that exist in the absence of a person’s intention, awareness, deliberation, or effort. Unlike explicit bias, which reflects people’s attitudes and beliefs that they consciously endorse, implicit bias results from cognitive processes that operate at a level below conscious awareness and without intentional control.108

Most implicit attitude measures rely on reaction times,109 and the Implicit Associations Test (IAT) is perhaps the most well-known reaction time task. The IAT gauges differences in how easy or difficult it is for people to associate individual exemplars of various social categories (whites vs. blacks, rich vs. poor, gay vs. straight, and so on) with abstract words and categories with evaluative implications (such as good vs. bad, pleasant vs. unpleasant). The IAT is based on the assumption that any exemplar (for instance, black) is cognitively associated with a corresponding evaluation (for instance, good or bad) and that pairing the exemplar with the corresponding evaluative words (for instance, black = bad) results in faster reaction times than pairing the exemplar with unrelated or incongruent evaluative words (for instance, black = good). The IAT is commonly used in laboratory and field research and its reliability110 and validity111 are well documented. Considerable research has indicated that most Americans display a pro-white/antiblack bias on the IAT.112 This bias has been demonstrated in children as young as six years old.113 In short, implicit bias is an invisible but pervasive reality of American life.

As Rachel Godsil observes, “The power of implicit bias to undermine educational opportunities of students of color are obvious—their contributions may fail to be recognized for their merit, they may well experience incidents in which they are treated differently by teachers, peers, and administration, or even assumed not to be students at all.”114 Below we explain why Godsil is right. More precisely, we discuss the relationship between implicit bias and educational outcomes. We begin with a 2010 study by Dr. van den Bergh and colleagues that explores the relationship between the implicit biases of teachers and the overall academic performance of students.115 We then explore how implicit biases affect both the evaluation of writing and the substantive content of letters of recommendations. As we will explain, each of the foregoing contexts in which implicit biases plausibly operate can impact the perceived competitiveness of a student’s admissions file.

a. Implicit Biases and Overall Academic Performance

The study by Dr. van den Bergh and colleagues focused on both implicit and explicit biases; however, our analysis will highlight the implicit bias dimensions of their findings. In short, the researchers found that teachers who scored high in implicit racial bias produced racial minority students with poor academic performance.116 Their study compared teachers’ implicit racial attitudes (as measured by the IAT) with actual students’ standardized test scores.117 They found that racial minority students in classes of teachers with negative implicit attitudes showed lower standardized test scores than racial minority students of teachers with more positive implicit attitudes. The study also found that the achievement gap between racial minority and racial majority students was higher among classes whose teachers had more negative implicit attitudes.

At the same time, there are limitations to the van den Bergh study. The correlational nature of the findings, the fact that the overall observed impact is modest (7–8 percent of the variance), and that the study was conducted with Dutch and Turkish/Moroccan students in a different educational context all suggest that we should interpret the results of the study with caution. On the other hand, the findings are consistent with studies in the United States showing that test scores of girls in math classes taught by teachers with negative implicit biases are lower than the test scores of girls from teachers with more positive implicit attitudes.118 Black students could be vulnerable to a similar dynamic, particularly because implicit bias is so widespread. In short, there is reason to believe that, in classrooms all across America, the implicit biases of teachers are negatively impacting black students’ test scores—the very test scores admissions officers use to screen students for admissions.

b. Implicit Biases and the Evaluation of Writing

There are other ways in which implicit biases can impact teachers’ evaluation of black students. Consider, for example, a relatively recent study in which evaluators rate the writing skills of blacks and whites.119 Reeves and colleagues simulated an evaluation of a legal memo with actual law firm partners. This study was not conducted on college campuses, but its high external validity offers a strong parallel to teachers’ and advisors’ evaluation of the work of black and white students. In this mock evaluation of legal memos, the researchers manipulated whether partners from several law firms in the United States reviewed and rated a legal memo ostensibly written by Thomas Meyer, either a black or a white associate. The study found that partners who reviewed the memo written by the black Thomas Meyer identified more errors, had more critical comments, and rated the memo worse than the white Thomas Meyer.

Interestingly, bias was found at the data gathering stage, when partners were searching for errors and critiquing the memo, and not at the rating stage, when partners were rating the overall quality of the writing effectively by adding up all of the errors. In other words, when Meyer was “black,” partners searched for and found more errors in the memo than when Meyer was “white.” Blackness seemed to have engendered a more critical eye. Then once the errors and negative comments were tabulated, the black Thomas Meyer was scored lower than the white Thomas Meyer.

A critical dimension of the study is that it suggests that it matters precisely when and where we look for bias. The partners discriminated on the front-end of the evaluation (when they were assigning errors), not on the back-end (when they aggregated those errors and made an overall evaluation of the writing). The fact that the partners followed fair procedures (counting the number of errors) to rate the memos did not cure the prior act of discrimination (the allocation of more errors to the memos they thought black attorneys wrote).

Think about the implications of the foregoing study for black students. Students write multiple essays—across the curriculum—in high school. The cumulative effect of the writing evaluation bias that Reeves and colleagues found could be quite significant.

c. Implicit Biases and Letters of Recommendations and Mentoring

Consider another implicit bias problem that a black student might encounter: letters of recommendation that coaches, teachers, and religious leaders write to champion the student’s abilities and promise. Implicit bias has been shown to affect how people write letters of recommendation, with implications for the success of the applicant in a competitive applicant pool.

In one study,120 researchers conducted an analysis of three hundred recommendation letters for women and men applying for medical school faculty positions and found that: (a) letters written for women were shorter; (b) they contained fewer assurances of competence and achievements but more assurances of compassion; and (c) they portrayed women as students and teachers rather than researchers and professionals. These differences led evaluators to perceive women as less competent than men, likely contributing to gender gaps in hiring, advancement, and receiving grants.121 Here, similar to the essay-writing study, bias altered how individuals constructed the abilities of women compared to men.

Studies of letters of recommendation show precisely how powerful implicit bias can be. Letter writers typically prepare letters as a personal favor to the applicant and often spend hours of their personal time to champion their student’s cause. Letter writers’ motivation to be racially biased in this context is low. If anything, their motivation to be biased in favor of the letter recipient is high. Yet even in a context where decisionmakers—here, letter writers—are motivated to do the right thing, implicit bias can constrain their capacity to do so.

d. Implicit Biases and Evaluations of Resumes

At least two studies suggest that implicit biases can shape how decisionmakers evaluate resumes. In one study, researchers122 asked male and female participants to evaluate the same resume with a randomly assigned male or female name. They found that both male and female evaluators gave the male applicants better evaluations in teaching, service, and research and were more likely to hire male over female applicants. This study is relevant to our analysis not only because black women, as women, likely experience this dynamic,123 but also because they likely face a similar dynamic with respect to race. Indeed, in a comparative study of job applications with African American-sounding names and white-sounding names,124 researchers found that applicants with African American-sounding names had to send an average of fifteen resumes to get one call back as opposed to ten resumes for applicants with white-sounding names.125 Moreover, the study found that, with respect to callback rate, having a white sounding names was equivalent to having eight additional years of experience.126

These resume studies are relevant to our analysis in at least two ways. First, faculty typically ask students for resumes as a predicate to writing letters of recommendations and refer to those resumes in the letters they write. There is reason to be concerned that, because of implicit biases, faculty are under-reading the resumes of African American students and thus under-describing black students’ abilities and promise. Second, admissions officials will read the resumes of prospective students to get a holistic picture of applicants and to assess students’ overall qualifications. Here, too, because implicit bias is so widespread, there is the potential for under-reading.

Of course, it’s hard to know the extent to which the resume bias problem we have described is a problem. We are aware of no empirical study quantifying the effect of resume bias on black college applicants. Our point is simply to suggest that there is reason to believe black applicants to colleges and universities are impacted by resume bias. It is another racial disadvantage black applicants across class likely experience that potentially renders their admissions files less competitive than those files would otherwise be.

C. Negative Institutional Culture

The final racial disadvantage we discuss that likely impacts the competitiveness of black students’ admissions files is negative institutional culture. To understand this phenomenon, it is helpful to note that targets of discrimination (for example, African Americans) focus not only on whether the people around them are explicitly or implicitly biased, but on whether the institutional cultures in which they are situated are explicitly or implicitly biased. In other words, socially marginalized groups focus on both discriminatory people and discriminatory institutions. They look for “cues” in the environment to ascertain whether that environment is one in which they are likely to succeed.127 The following are examples of environmental cues to which black students are likely to attend:

- Racial Demographics of Student Body. The lower the representation of black students within a particular institutional context, the greater the likelihood that those students will perceive that institution as unwelcoming and/or as one in which they are unlikely to 128

- Governing Ideology. The more an institution insists that race does not matter and encourages members within the institution to avoid discussing or engaging race, the more likely black students are to distrust the institution and question whether they belong.129 In this respect, a school that promotes a formal commitment to colorblindness is going to feel less welcoming to black students than a school that encourages Black students may interpret a school’s commitment to colorblindness as a signal that black students should “tone down” the degree to which they are black and “act white.”130 The more formally colorblind a school institutionally feels to black students, the stronger the pressure black students might experience to leave their “whole person” at home,131 compromise their sense of identity, and signal racial palatability.132

- Curricular Offerings and Content. There are at least two dimensions to how curricular offerings and content function as environmental First, institutions that offer very little in the way of courses on cultural and historical experiences outside of white European civilization are less likely to be ones in which black students feel comfortable or engaged.133 We call this the “what teachers teach” dimension of the curriculum. But there is a “how teachers teach” problem as well. A teacher might teach the history of the U.S. Constitution without discussing race; engage in debates about whether black students have a right to attend, or are smart enough to be at, the very institution in which they are taking the course; explore “both sides” of the argument as to whether blacks are more criminally inclined than whites; and call on black students only when the topic of race comes up. We recognize that a teacher might offer pedagogical reasons for pursing any of the foregoing modes of engagement, including the rationale that they facilitate the robust exchange of ideas. Our point is to highlight a potential distributional effect of how teachers teach: The creation of an unwelcoming institutional environment for black students that diminishes the likelihood that black students will succeed.

- Faculty and Administrative Leadership Demographics. Faculty and staff diversity, and not just student diversity, is an important environmental cue for black This might explain why, year after year, students across the country protest the lack of faculty and staff diversity.134 Underlying this effort is not just a commitment to antidiscrimination and equality but a sense that the more racially diverse the faculty and administrative leadership of a school, the more African Americans are going to feel like they belong at that school. There are three more concrete ways to understand why black students might pay attention to faculty and staff diversity.

First, faculty and staff can serve as mentors—even for students whose areas of interest do not converge with the faculty or staff member’s. Second, black faculty and staff can serve as role models, signaling by their very presence that black students belongs at and can thrive in the institution. Third, black faculty and staff can function as bridge-builders to multiple parts of the university, including facilitating interactions between black students and nonblack faculty and staff in the students’ areas of interest. The foregoing three reasons explain why black students are likely to pay attention to faculty and staff diversity. That diversity is an environmental cue for the kind of faculty and staff relationships students think they will have, the level of difficulty they think they will experience navigating the institution, and the overall racial climate of the school. - Institutional Signs of Stigma and Exclusion. Given the history of racism in educational access in the United States, many colleges and universities continue to harbor enduring signs of stigma and exclusion, manifested, for instance, in the names of Buildings at both elite and nonelite colleges and universities are sometimes named after people who supported the most racially subordinating aspects of American history, for example, slavery. Yet, these are precisely the spaces in which black students are expected to learn and take exams. Over the past year, students across the country have been organizing to rename numerous buildings, explaining that the existing names stigmatize students of color and send a message that they do not belong.135

A similar point can be made about college and high school mascots. For decades, Native Americans have been organizing around this issue. The problem here is not just one of cultural exploitation and appropriation,136 it is also one of racial stigma and environmental marginalization. The existence of these sports mascots stigmatizes Native Americans as a group, depressing self-esteem, feelings of community worth, and perceived possibilities for future academic success.137 This increased stigma renders the universities and high schools that the mascots purport to represent less welcoming and more hostile institutional spaces.138

There are more subtle signs of stigma and exclusion in educational settings that bear emphasis as well. Consider, for example, the practice of displaying the portraits of the founding faculty members on the walls throughout the university. This ubiquitous and seemingly neutral practice exacts a cost on students who were excluded during the colleges’ founding. Inevitably, the portraits hang on the wall of the most prominent parts of the university, including classrooms. Inevitably, the figures these portraits represent are white and male. And, inevitably, some of people the images depict have meaningful ties to slavery or Jim Crow. Yet, black students must interact with those portraits—sometimes daily—and with the legacies of exclusion those portraits represent. Those interactions serve as an implicit reminder that the institution is not one in which black students have historically belonged.