I. Introduction

How did the legal system in Germany enable the deprivation of the rights of Jews and, ultimately, the Holocaust in which six million Jews, including 1.5 million children, were murdered? How could state-sponsored and legalized evil be permitted in a civilized country in the twentieth century? The core answer, as this Essay will explain, is that German society—including, shamefully, the courts, judges, lawyers, and legal theorists—accepted and in many cases promoted Nazi[1] power and race-based injustice. Adolf Hitler’s absolute power as Führer was achieved incrementally, in plain sight, and purportedly under law.[2]

This Essay also explains the importance of Kristallnacht, which took place on November 9 and 10, 1938, throughout Germany and into Austria and Lithuania.[3] Kristallnacht was state terrorism against the Jewish community.

Finally, this Essay describes my parents’ miraculous escapes from the Nazis and their emigration to America. My father’s family escaped Nazi Germany in 1938 via Holland. My mother, then only sixteen, organized her and her mother’s emigration in 1939 from Lithuania. As we shall see, the events of Kristallnacht played an important role in my mother’s decision to escape.

II. Hitler's Ascension to Power in 1933: The Five Years Leading Up to Kristallnacht

Hitler became the German Chancellor on January 30, 1933.[4] The conditions in Germany that led to Hitler’s rise in power included frustration over the losses attributable to World War I, an economic depression, and a populace willing to embrace the argument that Jews were to blame for all these problems. Germans were also susceptible to the Nazis’ stated belief that Aryans by nature were an innately superior race.[5] Indeed, race became the foundational principle of Nazi rule and purported to justify their mistreatment of so-called inferior races, including the Jewish people.

Under the Weimar Constitution, political power was divided among the president, the cabinet, and the parliament (the Reichstag). The German president was the head of state and commander-in-chief and signed bills into law. Before Hitler’s ascension to power, the president appointed the chancellor, who was responsible to the Reichstag, and generally only represented the majority party, if any. As this Essay will describe, as chancellor, Hitler used his influence over President Paul von Hindenburg to amass power for himself.

One important tool used by Hitler was Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, known as the Dictatorship Article, which provided broad powers to the president in the event of an emergency.[6] Less than a month after Hitler became chancellor, the Nazis manufactured such an emergency when a fire gutted the Reichstag building which housed the German parliament. The importance of this event cannot be understated: it was equivalent to the burning of the United States Capitol. Although the fire was set by an individual Dutch Communist, the Nazis laid blame for it on the Communist Party, giving Hitler an excuse to ask President von Hindenburg to declare martial law under Article 48.[7]

On February 28, 1933, an executive decree popularly known as the Reichstag Fire Decree suspended important provisions of the Weimar Constitution, particularly those safeguarding individual rights and due process of law.[8] The decree permitted restrictions on the right to assemble, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press and removed all restraints on police investigations. With the decree in place, the police were free to arrest and incarcerate anyone without a specific charge, dissolve political organizations, and suppress publications. The decree also gave the central government the authority to overrule state and local laws and overthrow state and local governments. This law later became a permanent feature of the Nazi police state.

A month later, on March 24, 1933, the Reichstag passed the Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich, known as the Enabling Act, which would become the cornerstone of Hitler’s dictatorship.[9] The Enabling Act permitted Hitler to enact laws—including ones in conflict with the Weimar Constitution— without approval of either the Reichstag or President von Hindenburg.

Laws marginalizing the Jewish community and increasing the government’s authoritarian powers swiftly followed. For example, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, passed on April 7, 1933, excluded all Jewish people from civil service, including the ability to serve as judges or government attorneys.[10] In July 1933, the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party was declared to be the only political party in Germany.[11]

In April 1934, the Nazis created the National Socialist People’s Court (VGH). The VGH had jurisdiction over treason cases.[12]Judges were appointed to the VGH because of their loyalty to the Nazis and functioned as investigators and prosecutors as well as judges.[13] The purpose of the VGH was not to dispense justice but to punish the perceived enemies of the Nazis.[14]

Immediately after President Von Hindenburg’s death in August 1934, Hitler used his legislative powers to merge the offices of president and chancellor and assume the power and the authority of both under a new title—Führer. This merger of offices was approved by a national vote.[15] By September 1935, the Reichstag was completely controlled by the Nazi party.

On September 15, 1935, the Reichstag passed two new laws, now known collectively as the Nuremberg Race Laws. The Reich Citizenship Law decreed that only persons with German blood could be citizens; Jewish people lost their citizenship and their right to vote.[16] The Law for Protection of German Blood and Honor prohibited marriage between Germans and Jewish people and any sexual relations between Jewish and non-Jewish persons.[17]

More laws restricting and marginalizing the Jewish population followed. By December 1935, the dismissal of all Jewish professors, teachers, physicians, and lawyers had been ordered.[18] In August 1938, a law was enacted requiring all Jewish persons to add “Israel” or “Sarah” to first names of “non-Jewish origin.”[19] And in October 1938, the Reich Ministry of the Interior required passports of Jewish persons to be surrendered and invalidated unless they were stamped with a letter “J.”[20]

In September 1938, Germany, Italy, Great Britain, and France signed the Munich Agreement, requiring Czechoslovakia to surrender the Sudetenland to Germany. On his return to London, just six weeks before Kristallnacht, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain proclaimed that the result of the Munich Agreement would be “Peace for our time.”[21] History proved Chamberlain desperately wrong.

III. How and Why Germany's Legal and Judicial Systems Fail

We have seen how Hitler obtained and increased his dictatorial power, not in violation of, but in accordance with and assisted by German law. Some laws already existed and others were created by the Nazis. Indeed, when Hitler assumed the chancellorship in January 1933, the Nazis sought to establish their rule “within the framework of traditional law.”[22] The Nazis enacted laws and relied on the authority of those laws. How and why were the Nazis able to legally accomplish such dominance?

According to one historian:

There were essentially three principles that were held to be axiomatic for the entire field of administration as well as the judiciary: the principle of absolute rule by a leader (the Führer principle), the principle of the authority of the Party over the state, and the influence of race as the fundamental principle guiding affairs of state (‘racial inequality’).[23]

The courts, judges, lawyers, and legal theorists all joined in the Nazi plan and implemented it with vigor. In August 1934, German judges began taking an oath to follow Hitler, not the country’s constitution. All state officials, including judges, previously took the following oath: “I swear loyalty to the Constitution, obedience to the law, and conscientious fulfillment of the duties of my office, so help me God.”[24] The new version provided: “I swear loyalty to the Führer of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, obedience to the law, and conscientious fulfillment of the duties of my office, so help me God.”[25]

No German judge refused to take the revised oath.[26] Martin Gauger, a prosecutor at the state court in Wuppertal, Germany, appears to be the only public lawyer to resign his office rather than swear the required oath. As Gauger explained in a letter to his brother: “I could not swear an unlimited oath of loyalty and obedience to a man who is bound neither by the law nor the traditions of justice.”[27]

Wilhelm Stuckart was a German lawyer and judge—and an ardent Nazi. In 1935, as the director of the Reich Ministry of the Interior, he wrote, “Those actions of judges that seek to limit the political decisions of the Führer and ultimately obstruct them are in direct opposition to the central legal conception of the National Socialist state, namely the Führer Principle.”[28] Stuckart was one of the primary authors of the Nuremberg Race Laws.[29]Stuckart also attended the Wannsee Conference in 1942 and helped plan the administration of the Final Solution, Nazi Germany’s attempt to eradicate the Jewish people through mass murder in extermination camps.[30]

Hans Frank was Hitler’s personal lawyer, an early Nazi supporter, the founder of the Nazi Lawyers’ League, and the Reich Commissioner for Justice. In 1936, Frank, in describing the role of judges in light of the Führer Principle, wrote:

The judge is not placed over the citizen as a representative of the state authority, but is a member of the living community of the German people. It is not his duty to help enforce a law superior to the national community or to impose a system of universal values. His role is to safeguard the concrete order of the racial community, to eliminate dangerous elements, to prosecute all acts harmful to the community, and to arbitrate in disagreements between members of the community. The National Socialist ideology, especially as expressed in the Party programme and in the speeches of our leader, is the basis for interpreting legal sources.[31]

After 1939, Frank became the brutal viceroy of the part of German-occupied Poland not annexed to the German Reich.

Ultimately, the Führer Principle would be the basis for the Final Solution.[32] At his trial in 1961, in answering the question whether any law empowered the extermination of human beings in concentration camps, Adolf Eichmann testified that “[t]here was certainly no law . . . I only know that people relied on the saying, ‘Fuehrerworte haben Gesetzeskraft’ (the Führer’s words have the power of law) that was the saying at that time.”[33]

In 1936, in interpreting the Nuremberg Race Laws, the German Supreme Court effectively legitimized injustice based on race. The court’s opinion “eased the difficulties inherent in implementing anti-Jewish policies across a broad spectrum of cases from divorce to criminal race defilement. The court’s acceptance and application of the race laws served an important propaganda purpose, as well, by explicitly conferring legitimacy on racial discrimination and persecution.”[34] Thus, the “German legal profession, above all judges, had fully succumbed to the power of corruption, not in the material sense but in the ethical sense.”[35] VGH president Roland Freisler declared in 1935 that “[t]he German judicial system can take pride in being the first branch of government in the Third Reich to carry out its personnel policies, throughout the Reich and at all levels of the civil service, the principle that the movement, the people, and the state are one.”[36]

What was the response of institutions, including the courts, to the enactment of anti-Jewish laws and the enforcement of those laws by the police? Rabbi Leo Baeck, the leader of Germany’s Jewish community during the Nazi era, recounts that “the universities were silent, the courts were silent.”[37] Similarly, historian and Pulitzer Prize winner Saul Friedländer observed that “[n]ot one social group, not one religious community, not one scholarly institution or professional association in Germany and throughout Europe declared its solidarity with the Jews.”[38]

What about the lawyers? Distinguished Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg explains that “[a] lawyer necessarily had to face at every turn the critical question of harmonizing peremptory measures against Jews with law. In fact, this alignment was his principal task in the anti-Jewish work. Yet in the end lawyers . . . mastered those mental somersaults.”[39]

Did judges and lawyers take these actions out of fear? In hopes of career advancement? What personal qualities did these judges lack? I had the honor of having a conversation with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Professor Elie Wiesel.[40] I asked Professor Wiesel why German judges had so readily and uniformly enforced clearly unjust laws. He told me that judges in Nazi Germany lacked humanity and courage, and that they failed to appreciate the impact of their decisions on people.[41]

A recent book by Professor Herlinde Pauer-Studer of the University of Vienna persuasively argues that judges and lawyers also believed in Nazi doctrine.[42] According to Pauer-Studer, in responding to the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act, the leading legal theorists in Germany “aimed to outdo each other in their ideological efforts to serve the new rulers” and “helped to validate the emerging totalitarian form of rule.”[43]

What was the analysis of the legal theorists? They not only embraced the Nazi ideology but also “actively prepared the ground for the brutal and murderous persecution of Jewish members of German society.”[44] Pauer-Studer concludes, “Overall, the jurists provided the theoretical foundations for a state apparatus based upon the principles of National Socialism, including its notorious racial ideology and the quasi mythical status of the Führer.”[45] Significantly, these legal theorists and their writings were educating Germany’s future lawyers with Nazi ideology. Indeed, as Pauer-Studer points out, all the racial legislation, including the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Nuremberg Race Laws, “prepar[ed] the ground for the ‘ultimate solution’—the elimination of the Jews.“[46]

IV. The Stage Was Set for Kristallnacht in November 1938;What Happened Immediately Before, During, and After Kristallnacht?

With Nazi power complete and fully supported by the legal establishment, the stage was set for Kristallnacht. In October 1938, the Nazis expelled Polish-born Jewish people from Germany.[47] The Polenaktion or Polish Action was the first mass deportation of Jewish people from Germany. At the time, seventeen-year-old Herschel Grynspan was a Polish Jew living in France, but his family in Germany was subject to the Polish Action.[48] In protest, on the morning of November 7, 1938, Grynspan shot and killed a German diplomat inside the German embassy in Paris.[49]The Nazis used the event as the pretext for instituting a wave of destruction against Jewish people across Germany, Austria, and elsewhere.

Beginning the evening of November 9, 1938 and extending into the early morning hours of the next day, the Nazis burned, ransacked, and looted over 1,000 synagogues in Germany.[50]Jewish people were attacked in their homes and on the streets. At least ninety-one Jewish people were killed on Kristallnacht.[51] In towns, villages, and cities throughout Germany, Jewish-owned shops were destroyed, and the police rounded up and sent 30,000 Jewish men ages sixteen to sixty—one-fourth of all Jewish men in Germany—to concentration camps at Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald.[52] More than 1,000 of them would die there.[53]

Joseph Goebbels, the German Minister of Propaganda, urged the German people to take to the streets. In his diary, Goebbels recorded Hitler’s directions regarding Kristallnacht :

He decides: demonstrations should be allowed to continue. The police should be withdrawn. For once the Jews should get the feel of popular anger.

....I immediately give the necessary instructions to the police and the Party. Then I briefly speak in that vein to the Party leadership. Stormy applause. All are instantly at the phones. Now the people will Act.[54]

Goebbels’s diary also states that he gave orders to destroy Berlin’s main synagogue, while preserving nearby property owned by non-Jewish Germans.[55] In Vienna, which was under Nazi rule since March 1938, most of the city’s ninety-five synagogues were partially or totally destroyed.[56]

Kristallnacht meant that “the Third Reich had passed a milestone in the persecution of the Jews. It had unleashed a massive outbreak of unbridled destructive fury against them without encountering any meaningful opposition."[57] In the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht, life for Jewish people in Germany got even worse. The government announced that the cost of all damage to Jewish property would have to be paid by the Jewish owners themselves; payments by insurance companies would be confiscated by the government.[58] Jewish people would have to pay a collective fine, equivalent to more than $100 million, as punishment for the diplomat’s murder in Paris.[59]

Jewish newspapers and magazines were ordered to stop publication;[60] Jewish cultural activities were suspended indefinitely;[61] and Jewish children were ordered out of elementary schools.[62] Even park benches were segregated.[63] Next, Goebbels announced that no Jewish person could be a retailer, an exporter, a manager of a business, a foreman in a factory, or engage in handicrafts.[64] All businesses, real property, and valuable personal property—including stocks, jewelry, and fine art—owned by Jewish people must be sold.[65] No Jewish people were admitted to food stores or cafes, banks or pharmacies, or any place of entertainment.[66] These restrictions were in addition to those already established, starting in April 1933, in the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service.

As American scholar, professor, and rabbi Dr. Michael Berenbaum has described, Kristallnacht was the “end of the beginning and the beginning of the end.”[67] Germans have for many years referred to Kristallnacht as “the Reich Pogroms of November 1938,” an apt description that exposes the event for what it was: “sanctioned violence against the Jews.”[68]

V. Ruth Benjamin, My Mother

All of these actions against the Jewish people affected individuals and families. The following is the story of my mother’s family and her escape from Memel, a major seaport city in Lithuania. After World War I, Memel and its surrounding territory were detached from Germany, which sought to reacquire it in the lead up to World War II.

In the spring of 1938, the principal of sixteen-year-old Ruth Benjamin’s girls’ school in Memel, Mr. Schmidt, had been replaced; Ruth never saw him again. The new principal, Mr. Lobsin, was loyal to the Nazi party and was known for his hatred of Jewish people. He made the three Jewish girls in Ruth’s class sit on one side of the classroom while the ten non-Jewish girls sat on the other side. All these girls had attended school together for over ten years.

Years later, my mother recalled the torchlight procession and broken windows during the evening of Kristallnacht. She remembered that all Jewish doctors were arrested the day after Kristallnacht and cafes and shops had signs saying, “No Jews.”

On the morning after Kristallnacht, Ruth went as usual to her school. When she arrived, Mr. Lobsin told her that she and the other Jewish girls could never enter the school again, and that they should go to see their rabbi.

Ruth lived with her widowed mother, Rahel Benjamin. [69] After her experience at school the morning after Kristallnacht, Ruth returned home and told Rahel they had to leave Lithuania. It was clear to Ruth that they had no future there because she had no chance for an education. Ruth said they both should try to go to the United States where three of her older brothers already lived: Kurt in New York City and Max and Arthur in Los Angeles. Ruth’s sisters Rebecca Benjamin Osmianas and Erika Benjamin Graudens lived in Paris, and her sister Heddy Benjamin Gilis had already emigrated to Palestine.[70] Rahel’s brother Aaron Scher had emigrated to the United States in 1907 at age 20 and lived in Los Angeles. He later was instrumental in helping Ruth in the emigration process.

Ruth’s mother did not want to leave her home or hometown. Rahel had lived in Memel all her life, raised a family, and owned the building in which her home was located. She managed the large building and rented out space and rooms to businesses and boarders. On November 20, 1938, ten days after Kristallnacht, Bassya Benjamin, the wife of Ruth’s brother Kurt, wrote to Rahel from New York City. In a letter addressed to “Dear Mama,” Bassya pleaded for Rahel and Ruth to leave Memel and come to the United States: “For once, do not be considerate of anyone else, also not of your own children, and do what is best for you.”

Rahel finally relented. With her mother’s permission, Ruth applied for and succeeded in obtaining visas. Rahel and Ruth’s visa numbers were 190 and 191, out of only 397 visas authorized by the United States for all Lithuanians that year. Other members of their family were not so fortunate: Rahel’s brother Gershon decided to stay in Memel. He, his wife, and their children all perished in the Holocaust.

As part of the agreement with her mother, sixteen-year-old Ruth and sixty-year-old Rahel first travelled by train to Berlin to visit the grave of one of Ruth’s sisters, Erna. The trip of about fifteen hours took them across Germany to the Nazi capital. Their visas issued by the United States helped permit safe passage, but Ruth still asked her mother not to speak on the train because her accent and Yiddish language would alert the police or other passengers she was Jewish. Ruth was dark-skinned and she always believed the police on the train assumed she was Greek, not Jewish. During their return train trip to Memel, Ruth overheard a Nazi officer seated near them remark, “Soon, Memel will be ours again.”

Back in Memel, Ruth and Rahel made their final preparations to leave their homeland. Rahel sold her home and property, but the proceeds of the sale were confiscated by the government. Another long journey lay ahead of them, this time by train to Cherbourg, France, where they boarded a ship to America. Ruth had arranged for passage on what turned out to be the last passenger voyage of the Queen Mary. Ruth and her mother arrived in New York City on March 23, 1939, the same day Hitler’s forces occupied Memel.[71] Ruth and Rahel soon travelled to Los Angeles to be near relatives who had emigrated years earlier.[72]

It is important to emphasize and appreciate the remarkable and even astonishing nature of my mother’s arrangement of their emigration. As a sixteen-year-old, Ruth Benjamin obtained rare visas for herself and her mother, booked and led her mother through challenging travel, and successfully emigrated to America. Without her intelligence, will, and courage, none of the rest of our family’s story would have been possible.

On a personal level, Kristallnacht led directly to my mother’s emigration to America. In a much larger sense, Kristallnacht signaled to the world what the Nazis’ violent intentions were toward the Jewish community in Europe.

V. Ernest Fybel, My Father

A. The Escape of the Feibel Family from Germany

Ernst Wolfgang Feibel lived with his family in Osterode, Germany, a small medieval town at the foot of the Hartz Mountains.[73] In America, he was referred to as Ernest or Ernie Fybel; the change in spelling of the family’s last name is explained post. In 1934, at the age of seventeen, he joined a group of young Jewish people in Holland, working on a farm and awaiting emigration to Palestine or any country that would take them. In February of 1938, his father, mother, and younger brother Harry, then almost fourteen, met him in Holland after escaping Germany.[74]

My grandfather Kurt Feibel’s escape from Germany and his plan to save his family are the stuff of movies.[75]Largely because Kurt was a widely respected factory owner and community leader in Osterode, his own escape was aided by locals, including his employees, local police, and bankers. As a first step, Kurt’s chauffer and gardener, Gustav Appun, began making nightly trips to Berlin with crates of the Feibels’ personal belongings to be shipped to an uncle in America. The trip, almost 120 miles each way, had to be completed before sunrise to avoid raising suspicion.

In early 1938, the Gestapo had informed the Osterode police that the Gestapo intended to take away Kurt’s passport, but the local police insisted they should handle the matter.[76] Then, on February 3, 1938, the Osterode police went to Kurt’s office and demanded that he surrender his and his wife Käthe’s passports. Kurt actually had the passports in his desk drawer, but he told the local police they were with his travel agent in Berlin. The police informed Kurt they would return for the passports on the following Tuesday, February 8, alerting Kurt and Käthe to their specific deadline for leaving Osterode.

The next day, Käthe travelled to Berlin where Harry was in boarding school. To avoid suspicion, the two purchased round-trip tickets from Berlin to Zurich, Switzerland. They arrived in Zurich on February 5, 1938 and anxiously waited for word from Kurt.

Kurt finalized a previously agreed-upon sale of his house and his business to the factory’s general manager, Ferdinand Haase. The payment was transferred to a special bank account in the neighboring city of Goettingen. But when Kurt went there on Friday, February 4, 1938, the bank did not have enough cash on hand. Kurt was forced to wait until the following Monday to withdraw the remaining funds that would be necessary to ensure the family’s safe escape.

Once the funds were in Kurt’s hands on Monday, February 7, 1938, Kurt sent a portion via courier, due to the danger he faced as a Jewish person carrying so much cash. Kurt would meet the courier in Amsterdam, where they would recognize each other by the black paper silhouettes of Harry’s profile they each carried, which had been made at a Berlin arcade while Kurt was planning the family’s escape. After confirming Kurt had made it safely to Amsterdam, Käthe and Harry followed, and the family was reunited.

Haase’s daughter-in-law confirmed to us years later that the Gestapo came for the Feibels’ passports on Tuesday, February 8, 1938—as the local police had warned, and the day after Kurt escaped to Amsterdam. Many Germans helped the Feibels escape from Germany: Appun who, in addition to transporting the Feibels’ possessions to Berlin, drove Kurt to and from the bank in Goettingen and to the train station for his departure, factory manager Haase, the Osterode police, the factory workers, the bank employees, and the courier. None of them reported Kurt to the Gestapo. Had any one of them done so, there is no chance Kurt would have survived. As Haase’s daughter-in-law recalled when we spoke with her in 1999, “Everyone knew what was happening, but they wanted the Feibels to get out.”[77] We are all grateful for these humane and brave righteous gentiles.

A book published by historian Walter Struve includes the story of the Feibel family’s escape from Osterode and the support from those loyal to them:

Many people in Osterode, among them even party members, felt contentment, if not sympathy and excitement for Feibel’s successful flight . . . . His departure obviously required the silent knowledge and help of several people, who might not have known all the details about the flight. Detailed investigations followed the flight and police and the mayor were questioned in long interrogations. The Kreis Anzeiger (county paper) reported in late October 1938, that the Jew Feibel, who had fled the country, had lost his German citizenship.[78]

....

While some business owners were called names such as ‘Jew-slave,’ it seems that the people who helped Feibel didn’t experience any problems. It is unclear why they weren’t prosecuted. Without doubt, his discretion and his former position in the community benefitted him.

There are many comments in the sentiment, but there is one, in particular that is worth mentioning. In a statement by the mayor of Osterode, he wrote: “I was under the impression that even the [Nazis] spoke about and treated [Feibel] with respect.”[79]

Struve was correct to refer to this as “Feibel’s coup.”[80]

After spending five months in Amsterdam and with the help of their relatives in Southern California, my father and his family were able to emigrate to America. On July 16, 1938, Kurt, Käthe, Harry, and my father boarded the ship Veendam in Amsterdam. They arrived in New York Harbor on July 26, 1938.

As was true of Ruth Benjamin’s family, not all members of the Feibels’ extended family were as fortunate. Käthe’s brother Ernst Ries lived in Berlin with his non-Jewish wife and daughter. Before Kristallnacht, Ernst felt confident he would avoid disenfranchisement as a Jew because he was a veteran and had “always been a correct businessman and fellow human being.”[81] This oft-held belief did not become reality as Ernst perished in Auschwitz. His wife and daughter survived the war in hiding and were aided by his daughter’s boyfriend, later her husband, a Catholic working in a government office. Ernst’s wife wrote that as he looked out their apartment window on Kristallnacht, Ernst said to her, “Now it will be all over with us.”[82]

Akin to my mother’s extraordinary bravery in organizing and overseeing the emigration of herself and her mother, my grandfather Kurt Feibel’s foresight, courage, and devotion to his family enabled him to brilliantly organize their miraculous escape from Nazi Germany. He had the resources and intelligence, but the complicated escape was only possible because of his planning, the loyalty of his employees, especially Gustav Appun, and the courageous cooperation of other locals. The Gestapo interrogated Appun after the Feibels’ escape, but somehow no action was taken against him.

B. Kristallnacht in Osterode

Although the Feibels left Osterode in February of 1938, it is significant to note what would have happened to them had they stayed and what the remaining Jewish people in Osterode experienced.

Struve described Kristallnacht in Osterode and its impact on the synagogue:

The interior of the Jewish teacher’s apartment next to the synagogue was completely demolished. The synagogue itself was looted and its furnishings destroyed, but it was . . . not set on fire. The synagogue was located in such a way that the fire could not have been controlled. It would inevitably have spread to the surrounding buildings.[83]

Struve describes Jewish homes in Osterode broken into and looted, men taken away to prison, people interrogated, and property destroyed.[84] According to Struve, “[t]he adults who went to work the next morning after ‘Kristallnacht’ and the children on the way to school were shocked by the sight of human misery and material destruction.”[85] He concludes, “Shortly after ‘Kristallnacht’, all Jews in Osterode were instructed to only shop in one particular grocery store. Most retail stores now displayed signs saying ‘Jews undesirable.’”[86]

In 1999, my father and mother, along with my brothers Gary and Kirk and I traveled to Osterode. As we walked down a narrow street, my father—whose memory was already being attacked by Alzheimer’s—stopped and looked at a hollow, small building. He pointed to it and told us, “That’s where I was Bar Mitzvahed.” We discovered the building bore a bronze plaque that, in German and Hebrew, read:

This building was the Synagogue until 1938.

The Jewish community of Osterode.

Those who prayed to God here were disposed of and destroyed.

God you know my folly and my guilt is not hidden from you.[87]

C. The Feibels in America

Once in Los Angeles, Ruth enrolled in and graduated from Susan Miller Dorsey High School. Ruth and Rahel had no money and had to learn a new language. While seventeen-year-old Ruth was still in school she got a job as a seamstress in a factory. She worked in that job throughout World War II and rose to the title of “Sample Maker,” demonstrating her skills. In her graduation book from Dorsey High, a classmate wrote: “In our country, Ruth, you can find a place for your energy, initiative and real drive to succeed. Good luck.”

My father’s family also sought refuge in Los Angeles. They too had to learn a new language and figure out how to survive. They were poor, having spent their funds on emigrating. Unlike their comfortable lifestyle in Osterode where they owned a factory, a large home, and land, they worked low-skill jobs in America and persevered: Kurt delivered juices door-to-door and Käthe did domestic work.[88]

My father met a man through a Jewish refugee organization. He taught Ernie landscaping and helped him organize a door-to-door landscaping business. Harry got a job delivering newspapers for the Los Angeles Times and graduated from Alexander Hamilton High School.

My mother and father met in Los Angeles. They had much in common as refugees, including dealing with curfew and travel restrictions because they were regarded as aliens. They both worked hard—my father as a gardener and my mother as a seamstress—and married on February 14, 1943.[89]

Ruth and Ernie raised a family with love, a strong work ethic, and a focus on education. They were married over sixty-two years. Ernie worked in manual labor as a gardener until the age of forty when he became a realtor, an occupation he enjoyed and succeeded in for over thirty years. Ruth passed away in 2005, Ernie in 2010. During their lives in Los Angeles, they were both active in the Jewish community and held leadership positions in their synagogue and national Jewish organizations. Their memories have been honored by our family by, among other things, the establishment of the Ruth and Ernest Fybel Endowed Fund for Literature on Children of the Holocaust at the Samueli Library of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education at Chapman University, and by a bench named for them in the Holocaust Memorial Garden at the Jewish Community Center of Orange County.

After reaching draft age, Harry was drafted and joined the United States Army in September of 1943.[90] He was first assigned to the Persian Gulf Command in Iran and was redeployed to Marseille, France as part of the 1190th Engineering Company. In an ironic twist, he served as an interpreter for German prisoners of war. After VE-Day,[91] Harry was redeployed to the Pacific and arrived in Japan ten days after Japan’s surrender. My father was also drafted into the United States Army but he received an honorable discharge after only eighty-nine days because the Army could not deal with all of his food allergies.[92] After being teased in the Army by the mispronunciation of Feibel as Feeble, he changed the spelling of his surname to Fybel.

Harry, now age ninety-eight, remembers the inspiring sight of the Statue of Liberty as his family entered New York Harbor in July 1938. A successful businessman and artist, he has an impressive collection of artwork featuring the Statue, some beautifully painted by him. Harry and his wife Jeri have been married more than seventy years and still have a glow about them. They are generous supporters of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles; the Center features a tribute plaque for Kurt and Käthe.

VII. Concluding Personal Remarks

My family’s history and my careers as a lawyer and a judge fostered an interest in the role of the courts, judges, and lawyers in Nazi Germany. My study of the subject coincided with my increasing involvement in judicial ethics. From 2004 until my retirement in 2022, I was the Chair of the California Supreme Court’s Advisory Committee on the Code of Judicial Ethics. The Advisory Committee recommended amendments to the Code to the Supreme Court and, over time, the Code was amended to strengthen public protections in areas of impartiality, antidiscrimination, and elimination of bias.

Judicial independence from politics and the judge’s commitment to the United States Constitution and his or her state Constitution continue to have an impact. For example, in 2020, the appellate court on which I served decided a case in which two opposing political groups demonstrated in front of our courthouse on the day of oral argument.[93] The case involved the California Values Act which prohibits state and local law enforcement from engaging in certain acts related to immigration.[94] At issue was whether the Act was constitutional under the California Constitution as applied to charter cities’ control over their police departments.[95] The trial court held the Act unconstitutional, but we reversed and upheld the Act based on the law—the California Constitution and precedents of the California Supreme Court—rather than on politics or the demonstrators who, thankfully, all had a First Amendment right to express their views.[96]

As I now reflect on my career of almost thirty years as a lawyer and over twenty years as a judge and justice, one day stands out. February 8, 2002, was the day a hearing was held in a large appellate courtroom in downtown Los Angeles to hear testimony on my appointment by Governor Gray Davis to be an associate justice of the Court of Appeal, Fourth District, Division Three (Santa Ana). The members of the Commission hearing the testimony were the Chief Justice of California, the Attorney General of California, and the most senior justice of the Fourth District, the area including the Counties of Orange, San Diego, Riverside, and San Bernardino.

The courtroom was packed and overflowing into other rooms. My entire family, including my parents, my wife, our daughter Stephanie and son Dan, Dan’s future wife, Garland, friends, and professional colleagues from all parts of my life attended. Speakers on my behalf included the Dean of the UCLA School of Law, the former Chair of Morrison & Foerster, the firm where I had been a partner for almost twenty years, and a superior court judge. The final speaker on my behalf was the Honorable Shirley Hufstedler, the former Secretary of Education of the United States, justice on the California Court of Appeal, and judge on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. When Shirley Hufstedler stepped to the lectern all three Commission members sat up straighter in their chairs! The vote was unanimous and I was confirmed and took my oath.[97]

My dear mother Ruth realized the historical and personal significance of the moment. She turned to my wife Susan and said, “This is my revenge against Hitler.”

After introducing my family and expressing thanks, my acceptance speech was only three sentences:

As most of you know, I am a son of Jewish immigrants who escaped to America—my mother Ruth in 1939 from Lithuania and my father Ernest in 1938 from Germany via Holland.

My family history and the opportunities provided to us continue to be my motivation for public service.

I promise to always remember where I came from and to work diligently to give life in writing and in deed to the principles of democracy, liberty, and justice.

I am extraordinarily grateful and honored for my service as a judge. I took an oath to support and defend the Constitutions of the United States and the state of California; this oath did not mandate allegiance to any person, political organization, or policy. The guiding principles of serving as a judge should and do feature independence from politics and require integrity in each individual decision and throughout the decision-making process as a whole.

I have tried to fulfill the promise I made at my swearing in and hope and trust that I have made my mother and father proud.

VIII. Appendix

Image 1.

Ruth Benjamin, Memel, 1938.

Image 2.

Rahel Benjamin, Passport photo, 1938.

Image 3.

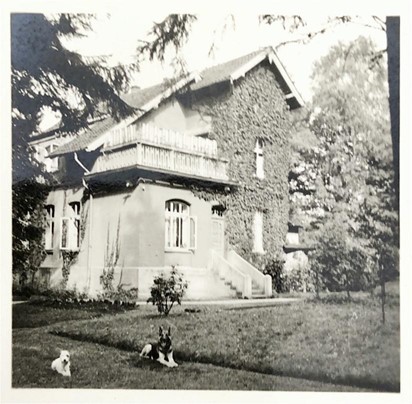

Feibel residence, Osterode.

Image 4.

Feibel factory and office buildings, Osterode.

Image 5.

Käthe and Kurt Feibel, late 1920s.

Image 6.

Ernst, Kurt, Käthe, Harry and Regina Feibel (seated), Osterode, c. 1934. This is the last photo of the family together in Osterode.

Image 7.

Ernie greeting Käthe and Kurt upon their arrival in Holland, February, 1938.

Image 8.

Photograph of the author with brothers Gary and Kirk Fybel in Osterode, 1999.

Image 9.

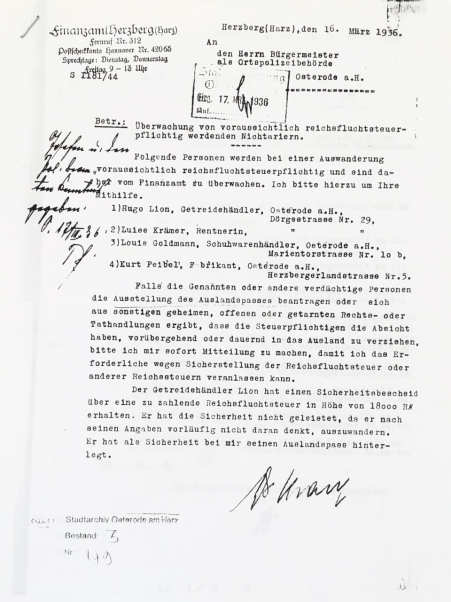

Letter from Gestapo to Osterode Bürgermeister, March, 1936.

Image 10.

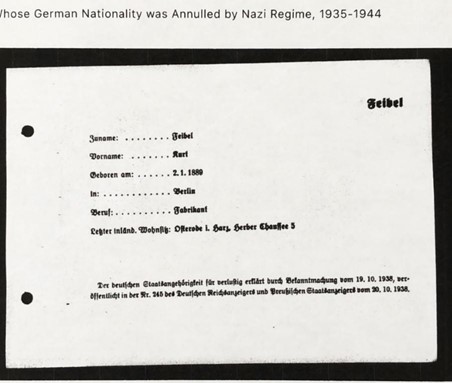

Notice of loss of German citizenship for Kurt Feibel.

Image 11.

Ruth and Ernie Fybel in discussion with Osterode resident, 1999.

Image 12.

Bronze plaque commemorating synagogue in Osterode.

Image 13.

Käthe and Kurt Feibel with the author and his brother Gary, Los Angeles 1952.

Image 14.

Ernie, Käthe, Ruth and Kurt Feibel, Ernie and Ruth's wedding day, February 14, 1943, Los Angeles.

Image 15.

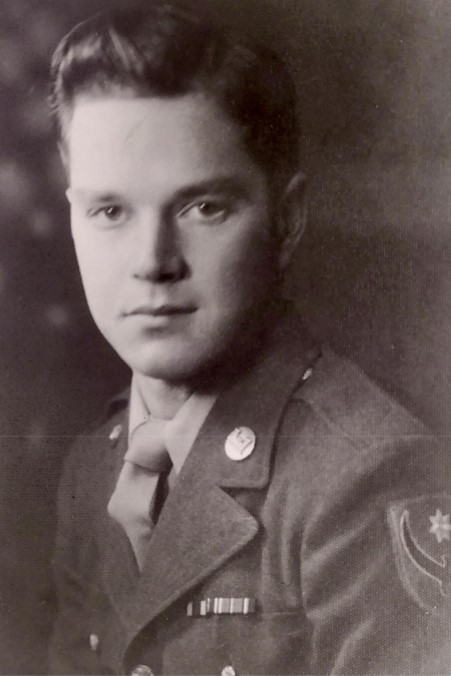

Photograph of Corporal Harry Fybel.

Image 16.

Photograph of Private Ernie Fybel.

Image 17.

Photograph of the author’s swearing-in ceremony, February 8, 2002, Los Angeles. Pictured are Chief Justice Ronald George, Justice Richard Fybel, Susan Fybel, Dan Fybel, Stephanie Fybel, Ruth Fybel, Ernie Fybel.

[1]. The term Nazi refers to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, or Nazi Party, the far-right racist and antisemitic political party which came to power in Germany in 1933. Led by Adolf Hitler, the Nazis controlled all aspects of German life and persecuted German Jews until losing power following the end of World War II. Nazi Party, U.S. Holocaust Mem'l Museum Holocaust Encyc., https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nazi-party-1[https://perma.cc/G2BH-J76D]

[2]. The author has written extensively about how the German lawyers, judges, and the legal system itself failed to protect the lives and freedoms of those persecuted, and Jews in particular. See generally Richard D. Fybel, The Absence of Judicial Ethics and Impartiality: The German Legal System, 1933–1945, in National Security, Civil Liberties, and the War on Terror 21, 25 (M. Katherine B. Darmer & Richard D. Fybel eds., 2011); Richard D. Fybel, When Mass Murder and Theft of All Human Rights Were “Legal”: The Nazi Judiciary and Judges, 66 Riverside 12 (2016); Richard D. Fybel, Assassins in Judicial Robes, Gavel to Gavel 30 (2013); Richard D. Fybel, When Mass Murder and Theft of All Human Rights Were “Legal”: The Nazi Judiciary and Judges 25 Cal. Litig 15 (2012); see also Rothman et al., California Judicial Conduct Handbook 25–26 (4th ed. 2017) (discussing the importance of empathy of a judge in the context of the failure of the German legal system).

[3]. The Nazis gave the name Kristallnacht to the violence of November 9 and 10, 1938. Kristallnacht translates to Crystal Night and has also been referred to over the years as the Night of Broken Glass. Kristallnacht, U.S. Holocaust Mem'l Museum Holocaust Encyc., https://www.ushmm.org/collections/bibliography/kristallnacht [https://perma.cc/2KM9-YD5N] (last visited Aug. 17, 2022).

[4]. See generally Introduction to the Holocaust, U.S. Holocaust Mem'l Museum Holocaust Encyc., https://perma.cc/4ZC2-MUVE] (last visited Aug. 17, 2022).

[5]. Beginning in the 19th century, the term Aryan was used to differentiate white Northern Europeans as a separate race. The Nazis saw the Aryan race as innately superior to other putative racial groups and they justified the Holocaust as a means of protecting themselves from inferior races. See generally David Anthony, The Horse, The Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World 9–11 (2007).

[6]. Article 48, U.S. Holocaust Mem'l Museum Holocaust Encyc., https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/article-48 [https://perma.cc/T3FT-JTSB] (last visited Aug. 17, 2022).

[7]. Herlinde Pauer-Studer, Justifying Injustice: Legal Theory in Nazi Germany 46 (2020); Richard Evans, The Third Reich In Power 11–12 (2006).

[8]. See William Meinecke, JR. & Alexandra Zapruder, U.S. Holocaust Mem'l Museum, Law, Justice, and the Holocaust 10 (2014), https://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/20140711-ljh-booklet-2nd-Edition.pdf [https://perma.cc/D4JP-4DLJ].

[9]. Id. at 17.

[10]. Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, U.S. Holocaust Mem'l Museum , https://www.ushmm.org/learn/timeline-of-events/1933-1938/law-for-the-restoration-of-the-professional-civil-service [https://perma.cc/H2LC-4Z67] (last visited Aug. 17, 2022).

[11]. Meinecke & Zapruder, supra note 8, at 21.

[12]. H.W. Koch, In the Name of the Volk: Political Justice in Hitler’s Germany 3 (1997).

[13]. Id. at 4.

[14]. Ingo Müller, Hitler’s Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich 192 (Deborah Lucas Schneider trans., 1991) (1987).

[15]. Pauer-Studer, supra note 7, at 49.

[16]. Id. at 30-32.

[17]. Id.

[18]. One of my mother’s brothers, Max Benjamin, was expelled from medical school in Berlin because he was Jewish. When asked how his non-Jewish classmates reacted to his expulsion, he said they were happy because it meant less competition for them. Similarly, after Jewish law professors and legal officials were dismissed under the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service in April 1933, “[Nazi] loyal theoreticians scooped up the[ir] posts.” Pauer-Studer, supra note 7, at 133.

[19]. Law on Alteration of Family and Personal Names, U.S. HOLOCAUST MEM’L MUSEUM, https://www.ushmm.org/learn/timeline-of-events/1933-1938/law-on-alteration-of-family-and-personal-names [https://perma.cc/J3N5-GNLP] (last visited Aug. 17, 2022); MMeinecke & Zapruder, supra note 8, at 28.

[20]. Meinecke & Zapruder, supra note 8, at 29.

[21]. Roger Parkinson, Peace for Our Time: Munich to Dunkirk-The Inside Story 62 (1972).

[22]. Diemut Majer, "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe, With Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939-1945 6 (Peter Thomas Hill, Edward Vance Humphrey, & Brian Levin trans., 2003).

[23]. Id. at 10.

[24]. Meinecke & Zapruder,supra note 8, at 23–24.

[25]. Id.

[26]. Koch, In the Name of the Volk: POlitical Justice in Hitler's Germany 119. (1997).

[27]. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, The Courage to Say “No”: Martin Gauger and the Oath to Hitler, Nat'l Dist. Att'ys Ass'n (Nov. 20, 2020), https://ndaa medium.com/the-courage-to-say-no-martin-gauger-and-the-oath-to-hitler-9dfb430d377 [https://perma.cc/96PU-8CLL]. After Gauger’s resignation, he became a legal advisor for the Confessing Church, a movement within the German Evangelical Church that opposed Nazi intervention in religious affairs. Id. Gauger refused military service after the onset of World War II, believing the Nazis were fighting “an immoral war of aggression.” Id. Despite fleeing to the Netherlands, he was arrested and ultimately imprisoned at the Buchenwald concentration camp, where he was murdered in the gas chamber at age 35. Id.

[28]. Meinecke & Zapruder,supra note 8, at 75.

[29]. Id.

[30]. Pauer-Studer, supra note 7, at 145.

[31]. Evans, supra note 7, at 73.

[32]. At the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, the participants agreed upon the implementation of the decision to exterminate all Jewish people in Europe. Those at the conference used the phrase “evacuation to the East.” Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution (1933–1939) 339–40 (1997). As scholar, professor, and rabbi Dr. Michael Berenbaum notes, “The Nazi used language deliberately, deliberately and deceptively. ‘Resettlement in the East’ did not mean resettlement in the east. It meant deportation to death camps. ‘Executive Measures’ was the way the Nazis referred to mass executions. They used one term correctly: ‘The Final Solution to the Jewish Problem,’ the annihilation of the Jews, all Jews, men, women and children was all too final.” Michael Berenbaum, The Reich Pogroms of November 1938: The End of the Beginning and the Beginning of the End, Berenbaum Grp.(Nov.3,2013), http://berenbaumgroup.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=130:75-years-after-kristallnacht-&catid=34:recent-publications&Itemid=48 [https://perma.cc/K4S7-WRER].

[33]. The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 100 (Part 4 of 5), Nizkor Project http://nizkor.com/hweb/people/e/eichmann-adolf/transcripts/Sessions/Session-100-04.html [https://perma.cc/8B37-MJPQ] (last visited Aug. 17, 2022).

[34]. Meinecke & Zapruder,supra note 8, at 32.

[35]. Koch,supra note 12, at 119.

[36]. Ingo Müller, Hitler’s Justice: The Courts Of The Third Reich 192 (Deborah Lucas Schneider trans., 1991) (1987).

[37]. Eva Fogelman, Conscience & Courage: Rescuers Of Jews During The Holocaust 24 (1994).

[38]. Saul Friedländer,nazi Germany And The Jews:the Years Of Extermination(1939-1945) xxi (2008).

[39]. Raul Hilberg, Perpetrators Victims Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe (1933–1945) 65-66 (1992).

[40]. Conversation with Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, in the Home of Chapman University’s President (Mar. 27, 2011) (unpublished notes) (on file with author).

[41]. Id.

[42]. See generally Pauer-Studer, supra note 7, at 58, 67.

[43]. Id.

[44]. Id. at 67.

[45]. Id. at 77.

[46]. Id. at 151.

[47]. See generally Martin Gilbert, Kristallnacht: Prelude To Destruction 23 (2006).

[48]. Id. at 24.

[49]. Id. at 24-25, 27.

[50]. Id.

[51]. Id. at 13.

[52]. Id.

[53]. Id.

[54]. Friedländer,supra note 32, at 272.

[55]. Id.

[56]. Gilbert,supra note 47, at 33.

[57]. Evans,supra note 7, at 589.

[58]. Friedländer,supra note 32, at 281.

[59]. Gilbert,supra note 47, at 145-46.

[60]. Friedländer,supra note 32, at 283.

[61]. Id. at 281, 283, 285;Gilbert,supra note 47, at 147.

[62]. Friedländer,supra note 32, at 282, 284-85.

[63]. Id. at 282.

[64]. Gilbert,supra note 47, at 145-46.

[65]. Friedländer,supra note 32, at 281, 284.

[66]. Gilbert,supra note 47, at 146.

[67]. Michael Berenbaum, Night of Broken Jews: Remembering Kristallnacht, Jewish(Nov. 7,2018), https://jewishjournal.com/cover_story/241592/end-beginning-beginning-end [https://perma.cc/CAW5-5G2E].

[68]. Michael Berenbaum, 75 Years After Kristallnacht: The Reich Pogroms of November 1938: The End of the Beginning and the Beginning of the End, Berenbaum Grp. (Nov. 3, 2013), http://berenbaumgroup.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=130:75-years-after-kristallnacht-&catid=34:recent-publications&Itemid=48 [https://perma.cc/2JSJ-RVSC].

[69]. See Appendix Images 1-2(Ruth Benjamin, Memel, 1938; Rahel Benjamin, Passport photo, 1938).

[70]. Rebecca escaped from France with her husband Yascha Osmianas and young son Rene by hiking over the Pyrenees Mountains into Spain. Erika spent the war years in hiding in France; her husband Herman Graudens perished, while their daughter Colette was hidden in a French convent throughout the war. After the war, Rebecca and her family, Erika and Colette all emigrated to America. Heddy remained in Israel as a nurse and raised a family with her husband Leo.

[71]. Hitler Takes Over Memel in Triumph, N.Y. Times, Mar. 24, 1939, 3.

[72]. Rahel’s brother Aaron Scher and Ruth’s oldest brother Arthur Benjamin had arrived in Los Angeles before 1930. As discussed above, Ruth’s brother Max was expelled from a medical internship in 1935. He emigrated to the United States in January 1936, attended medical school, and became a successful physician. Ruth’s brother Kurt had been a member of the Memel City Council and sensed that the situation for Jewish people was worsening before he emigrated to New York in June 1937 with his wife and son. Arthur, Max, and Kurt Benjamin filed affidavits in support of Rahel and Ruth’s applications for immigration visas. (Affidavits are on file with author.)

[73]. See Appendix Images 3-6 (photographs of Feibel residence, Osterode; Feibel factory and office buildings, Osterode; Käthe and Kurt Feibel, late 1920s; Ernst, Kurt, Käthe, Harry and Regina Feibel (seated), Osterode, c. 1934. This is the last photo of the family together in Osterode.)

[74]. See Appendix Image 7 (photograph of Ernie greeting Käthe and Kurt upon their arrival in Holland, February, 1938).

[75]. The history and chronology of my father’s family’s escape from Germany have been compiled through the following sources: conversations and a videotaped interview with Ernest Fybel; conversations and interviews with Harry Fybel, including his videotaped testimony given to the USC Shoah Foundation; the author’s personal interview in 1971 of Gustav Appun and his wife Berta Appun (who had also served as Kurt and Kathe’s cook) in Osterode, Germany (a trip the author and his wife took specifically to personally thank the Appuns); interviews conducted in Osterode, Germany in 1999 by the author, his mother, and his brothers Gary and Kirk of Osterode’s bürgermeister (mayor), Osterode’s town historian, and Christa Gerke-Haase, the daughter-in-law of Ferdinand Haase. See Appendix Image 8 (photograph of the author with brothers Gary and Kirk Fybel in Osterode, 1999).

[76]. See Appendix Image 9 (photograph of a letter from Gestapo to Osterode Bürgermeister, March, 1936).

[77]. Interview of Christa Gerke-Haase (1999) (on file with author).

[78]. See Appendix Image 10 (photograph of Notice of loss of German citizenship for Kurt Feibel).

[79]. Walter Struve, The Rise And Ruling Of National Socialism In A Small Industrial City: Osterode Am Harz, 1918-1945 383–84, n. 239 (Doris Herwic trans., 1992). This book is only available in German, under the name Aufstieg Und Herrschaft Des Nationalsozialismus In Einer Industriellen Kleinstadt: Osterode Am Harz, 1918–1945.

[80]. Id. at 384. The county paper misreported that Kurt lost his German citizenship after fleeing the country. As noted previously, all Jewish people lost their citizenship in 1935 as a result of the Nuremberg Race Laws.

[81]. Interview of Charlotte Ries Giesen, Ernst Ries’s Daughter (Nov. 23, 1992) (on file with author). The interview was conducted by a graduate student at the Gray Monastery where Charlotte had been a student and where she was hidden during the war. This interview was part of the school’s project to document stories of Jewish students who had attended the school.

[82]. Affidavit of Charlotte Ries, Ernst Ries’s Wife, in Support of Claim for Compensation for the Murder of Ernst Ries in Auschwitz (on file with author).

[83]. Struve, supra note 79, at 391. During our 1999 visit to Osterode, we talked with a woman who was an eyewitness to the damage to the Osterode synagogue. She had lived across the street from the synagogue; everything in the synagogue was destroyed and she saw the Nazis take away the rabbi and his wife. She also told us her uncle had worked stuffing pillows in Kurt’s factory, and that Kurt was respected in Osterode. See Appendix Image 11 (photograph of Ruth and Ernie Fybel in discussion with Osterode resident, 1999).

[84]. Struve, supra note 79, at 389-90. Translated by computer generated translation.

[85]. Id. at 392. Translated by computer generated translation.

[86]. Id. at 396. Translated by computer generated translation.

[87]. See Appendix Image 12 (Photograph of bronze plaque commemorating synagogue in Osterode).

[88]. See photograph of Käthe and Kurt Feibel with the Author and his brother Gary, Los Angeles 1952. Appendix Image 13.

[89]. See Appendix Image 14 (photograph of Ernie, Käthe, Ruth and Kurt Feibel, Ernie and Ruth's wedding day, February 14, 1943, Los Angeles).

[90]. See Appendix Image 15 (photograph of Corporal Harry Fybel).

[91]. Victory in Europe Day, May 8, 1945, marked the total surrender of the German troops to the Allied forces.

[92]. See Appendix Image 16 (photograph of Private Ernie Fybel).

[93]. See generally City of Huntington Beach v. Becerra, 44 Cal.App.5th 243(2020). The case was referred to in the media as the Sanctuary City case. I was the author of a unanimous opinion by the appellate court. The California Supreme Court unanimously denied review.

[94]. Prohibited acts under the California Values Act include but are not limited to inquiring into immigration status, placing individuals on an immigration hold, and using personnel or resources to participate in certain immigration enforcement activities. Gov. Code, § 7284.6, subd. (a).

[95]. City of Huntington Beach, supra note 92, at 247-48.

[96]. Id. at 248.

[97]. See Appendix Image 17 (photograph of the author’s swearing-in ceremony, February 8, 2002, Los Angeles; pictured are Chief Justice Ronald George, Justice Richard Fybel, Susan Fybel, Dan Fybel, Stephanie Fybel, Ruth Fybel, Ernie Fybel).