Introduction

Legal scholars have long loved the infield fly rule, the often-mysterious baseball rule that, in certain situations, makes a batter out even if an infielder fails to catch an easily catchable fly ball.[ref]Major League Baseball, Official Baseball Rule 2.00 (2013) (Infield Fly); Howard M. Wasserman, The Economics of the Infield Fly Rule, 2013; Utah L. Rev.479, 491.[/ref] This is a subspecies of the broader academic fascination with baseball.[ref]E.g., Baseball and the American Legal Mind ix–x, 3 (Spencer Weber Waller et al. eds., 1995); Roger I. Abrams, Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law 3 (1998); A. Bartlett Giamatti, Take Time for Paradise: Americans and Their Games (1989); Neil B. Cohen & Spencer Weber Waller, Taking Pop-ups Seriously: The Jurisprudence of the Infield Fly Rule, 82 Wash. U. L.Q. 453, 454 (2004); Aside, The Common Law Origins of the Infield Fly Rule, 123 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1474 (1975).[/ref] In The Economics of the Infield Fly Rule, I defended the rule as part of baseball’s structure and logic, justified by concerns for an equitable balance and distribution of costs and benefits between competing sides on individual plays.[ref]Wasserman, supra note 1, at 493.[/ref]While baseball still calls itself the national pastime, professional football long ago surpassed it in popularity, with college football now close behind.[ref]Football Continues to Be America’s Favorite Sport; the Gap With Baseball Narrows Slightly This Year, Harris Interactive (Jan. 17, 2013), http://www.harrisinteractive.com/NewsRoom/HarrisPolls/tabid/447/ ctl/ReadCustom%20Default/mid/1508/ArticleId/1136/Default.aspx.[/ref] Yet the academic fascination has not transferred to football as a game, as opposed to as a powerful institution at the center of important legal controversies.[ref]Cf. Michael A. McCann, American Needle v. NFL: An Opportunity to Reshape Sports Law, 119 Yale L.J. 726 (2010) (discussing antitrust implications of league licensing deals); Howard M. Wasserman, Introduction: Football at the Crossroads, 8 FIU L. Rev. 1 (2012) (introducing a symposium on head trauma in football); Kerri L. Stone, Why Does It Take a Richie Incognito for Us to Start Talking About Bullying?, Huffington Post (Nov. 16, 2013, 12:35 PM), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kerri-l-stone/post_6167_b_4276891.html (discussing new public awareness of workplace bullying following report of bullying in National Football League (NFL) locker rooms).[/ref] And no one has yet explored the rules of football in search of a counterpart to the infield fly rule. Rather, the supposed absence of anything akin to the infield fly rule in football is an arrow in the quiver against that rule in baseball. Critics argue that if football does not have or need something akin to the infield fly rule, then baseball does not need it either.

While no football rule enjoys the infield fly rule’s pedigree or intellectual cult following, football is filled with game situations and corresponding rules cut from its intellectual and logical cloth, seeking similarly equitable cost-benefit distribution. Having just marked another Super Bowl Sunday[ref]Super Bowl XLVIII was played on February 2, 2014—the day before this essay was published. It was played outdoors in New Jersey, the first cold-weather outdoor Super Bowl. Jim Litke, Super Bowl: Cold Weather, Cold Cash, Philly.com (Dec. 27, 2013, 12:00 AM), http://www.philly.com/philly/news/local/20131226 _Super_Bowl__Cold_weather__cold_cash.html.[/ref] as an unofficial national holiday,[ref]Michael Jay Friedman, Super Bowl Sunday an Unofficial Holiday for Millions, IIP Digital (Feb. 1, 2012), http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/article/2006/02/20060202162836jmnamdeirf0.5 559656.html#axzz2paVNWI2i.[/ref] it is a good time to consider football as a source of game situations in which special rules are necessary to ensure equitable cost-benefit exchanges. Coincidentally and beneficially, two recent Super Bowls[ref]In Super Bowl XLVI, played in February 2012, the New York Giants defeated the New England Patriots 21–17. Nick Meyer, Super Bowl XLVI Results: Giants Defeat Patriots in Final Minutes, Yahoo! Sports (Feb. 5, 2012), http://sports.yahoo.com/nfl/news?slug=ycn-10930532. In Super Bowl XLVII, played in February 2013, the Baltimore Ravens defeated the San Francisco 49ers 34–31. Super Bowl XLVII New Orleans, NFL, http://www.nfl.com/superbowl/47 (last visited Jan. 6, 2014).[/ref] and several regular season games from the just-completed 2013 regular season have featured plays illustrating how and when cost-benefit imbalances arise in football and how the game’s rulemakers respond. And taking advantage of this journal’s online format, I have embedded video and photos of these critical plays as part of the Essay.

I. Limiting Rules

In my recent contribution to infield fly rule scholarship, I introduced the concept of limiting rules, defined as unique, situation specific rules that override ordinary rules, practices, and strategies in particular game situations. I further explained that such rules are necessary when the cost-benefit exchange on a play shifts inequitably in favor of one side and against the other.[ref]Wasserman, supra note 1, at 486.[/ref]

A limiting rule is warranted when a game situation is defined by all of four features. First, the play in question produces an overwhelming, unfair, and inequitable cost-benefit disparity, in which one side gains substantial benefits while incurring no, or virtually meaningless, costs and the opposing side incurs substantial costs while obtaining no, or virtually meaningless, benefits. Second, the play involves a disparity in control—the advantaged side is free to manipulate the situation to its benefit, while the disadvantaged side is helpless to stop or counter that manipulation within the game’s regular rules and practices. Third, the advantaged side achieves these disparate benefits by intentionally failing or declining to perform the athletic skills they are expected to perform under the game’s ordinary practices and strategies. And fourth, the opportunity to gain that overwhelming cost-benefit advantage incentivizes the advantaged side to intentionally fail or decline to perform those expected athletic skills whenever the situation arises.[ref]Id. at. 486–89.[/ref]

The consequent limiting rule imposes the outcome that would result on the play if the advantaged team had acted consistent with ordinary expectations by performing the game’s ordinary athletic skills in the expected manner. By imposing that outcome, the limiting rule removes the opportunity and incentive for players to act contrary to expectations or to fail, or decline, to perform expected athletic skills in search of extraordinarily greater benefits.[ref]Id. at 489.[/ref] The infield fly rule—which declares the batter out even if the fielder fails to catch an easily catchable fly ball[ref]Major League Baseball, Official Baseball Rule 2.00 (2013) (Infield Fly).[/ref]—is the paradigm of a limiting rule.[ref]Wasserman, supra note 1, at 493–97.[/ref]

Importantly, this framework recognizes that sports often involve cost-benefit tradeoffs. Teams readily accept suboptimal outcomes on individual plays; each gains some benefits, surrenders some benefits to the opponent, and incurs some costs, each hoping to come out ahead on the exchange. When that cost-benefit exchange is relatively fair and equitable, limiting rules are unnecessary. Rather, the situation can and should be left to the game’s ordinary rules, practices, and strategies. Only when the cost-benefit imbalance is significantly disparate and inequitable and too weighted toward one side and against the other does a limiting rule become necessary.[ref]Id. at 489–90.[/ref]

Nor is this framework limited to sports. I previously analogized the rules of sport to the rules of procedure, as both establish the framework and structure in which disputes, whether athletic or judicial, are contested and resolved.[ref]Id. at 484.[/ref] Both sports rules and procedural rules are designed to ensure a level playing field, with rulemakers occasionally tweaking the background rules to maintain that level field.[ref]Id. at 485–86.[/ref] When holes in the existing framework, whether of a sport or litigation, produce extreme cost-benefit disparities, limiting rules restore a more optimal balance.[ref]Id. at 487.[/ref]

Rulemakers must continually study the game, identifying situations in which the cost-benefit disparity becomes too inequitable and a limiting rule is appropriate to restore a proper balance. Often it takes only a single play. What became the infield fly rule was enacted in 1894 in direct response to a single play in an 1893 game.[ref]Id. at 491–92.[/ref] In the National Football League (NFL), the task of studying the game and recommending rule changes falls to the Competition Committee, a nine-person committee of coaches, owners, and front-office personnel.[ref]Four Coaches Named to Coaches Subcommittee of Competition Committee, NFL Comm. (Apr. 15, 2013), http://nflcommunications.com/2013/04/15/four-coaches-named-to-coaches-subcommittee-of-competition-committee-2.[/ref] Continuing the analogy to procedural rules, the Competition Committee is akin to the various committees and subcommittees that continually study how the federal rules of practice and procedure are functioning and recommend changes, often to restore necessary cost-benefit balance.[ref]See, e.g., 28 U.S.C. § 2073(a), (b) (2012); Catherine T. Struve, The Paradox of Delegation: Interpreting the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 150 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1099 (2002).[/ref] And just as the rules committees propose some changes to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in response to specific decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States,[ref]See, e.g., Fed. R. Civ. P. 15 advisory committee’s note to 1991 amendment (revising Rule 15(c)(3) to overturn result of Supreme Court decision in Schiavone v. Fortune, 477 U.S. 21 (1986)); see also Howard M. Wasserman, The Roberts Court and the Civil Procedure Revival, 31 Rev. Litig. 313, 332, 346 (2012) (describing proposals and arguments aimed at overturning the Supreme Court’s recent pleading decisions).[/ref] the NFL’s Competition Committee is most likely to respond to problematic plays occurring in the Super Bowl.

II. Football and Limiting Rules

This definitional framework, created to explain baseball and its rules, has explanatory value for many sports, including football. The framework can be used to identify game situations in which the cost-benefit disparity is so imbalanced and outsized as to warrant a limiting rule grounded in the same logic as the infield fly rule, as well as those situations that reflect equitable cost-benefit exchanges not warranting limiting rules.

In applying this framework to football, two preliminary points are in order.

First, unlike baseball, football is timed. The goal in baseball is simple: score the most runs possible and get the necessary outs, twenty-seven in the ordinary nine-inning game, to end the game. The offensive team thus typically wants to maximize the runs it scores and minimize the outs it surrenders.[ref]A batting team only rarely has an incentive not to try to score runs. For example, a Major League game becomes a regulation game after five innings have been completed, four-and-a-half innings if the home team is leading. Thus, a team leading as rain threatens may forgo trying to score additional runs in favor of trying to end its turn at bat quickly to ensure that enough innings are completed to make a regulation game. See Major League Baseball, Official Baseball Rules 4.10(a), (c) (2013).[/ref]

The goal in football is not necessarily to score as many points as possible but simply to score more points than the opponent when time expires. Thus, in determining when a team is acting consistently with the game’s rules and strategies and performing the expected athletic skills, we must consider not only the goal of scoring points but also the goals of having time run off the clock and denying the opponent an opportunity to score. For example, a football team leading late in the game and in possession of the ball may run plays not necessarily designed or intended to lead to a score or even to gain yards, but only to keep the clock running—the clock continues running between plays unless the ball goes out of bounds or a thrown pass is incomplete[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rule 4-4 (2013).[/ref]—and to maintain possession of the ball, thus denying the opponent possession and the opportunity to score.

Second, strategy over the course of a football game emphasizes field position in addition to points. This encourages strategy in which one team surrenders possession of the ball—and thus the opportunity to score points—in exchange for putting the opponent in a less advantageous position on the field. For example, teams often punt the ball away on fourth down from near midfield, despite statistical studies suggesting it is better to try to gain the short yards for a new set of downs.[ref]See Brian Burke, The 4th Down Study – Part 4, Advanced NFL Stats (Sept. 16, 2009), http://www.advancednflstats.com/2009/09/4th-down-study-part-4.html; Brian Burke, The 4th Down Study – Part 3, Advanced NFL Stats (Sept. 16, 2009), http://www.advanced nflstats.com/2009/09/4th-down-study-part-3.html; Brian Burke, The 4th Down Study – Part 2, Advanced NFL Stats (Sept. 15, 2009), http://www.advancednflstats.com/2009/09/4th-down-study-part-2.html; Brian Burke, The 4th Down Study – Part 1, Advanced NFL Stats (Sept. 15, 2009), http://www.advancednflstats.com/2009/09/4th-down-study-part-1.html.[/ref] The prevailing view among coaches, however, is that it is better to have the opponent gain possession deeper in its own territory, with further to travel for a score, than near midfield if the fourth-down play fails.

Both moves—playing to run time off the clock and playing for advantageous field position—reflect expected skills and strategy within the game’s basic framework. One team incurs the cost of failing to gain yardage on a play while enjoying the benefit of having time lapse off the clock. Or one team incurs the cost of surrendering possession in exchange for the benefit of better field position, while the other team gains the benefit of possession and a chance to score against the cost of starting from a less advantageous place on the field. How these exchanges play out—and which team ultimately gains the most—depends on subsequent events.

With these caveats about football in mind, we can examine several game situations—drawn from two recent Super Bowls and the most recent regular season—to illustrate how prevalent limiting rules are or might be in football and how those limiting rules function.

A. Intentional Penalties

1. Running Time Through Penalties

In Super Bowl XLVI, played in 2012, the New York Giants led the New England Patriots 21–17 with seventeen seconds remaining in the game. The Patriots had the ball at their own forty-four yard line, needing a touchdown to win the game. The Patriots ran a play that resulted in an incomplete pass, running eight seconds off the clock. But the Giants were called for having too many players on the field. The incomplete pass became a nonplay and the ball advanced five yards to the Patriots’ forty-nine yard line. But those eight seconds remained off the clock. Thus, while the Patriots were five yards closer to the winning touchdown, only nine seconds remained in the game. They were able to run only one more play—a long pass that fell incomplete—and the Giants won the game.[ref]See Eli Manning, Giants Thwart Pats Again to Cap Magical Run With 4th Super Bowl Title, ESPN NFL, http://scores.espn.go.com/nfl/recap?gameId=320205017 (last visited Dec. 24, 2013).[/ref]

Figure 1.

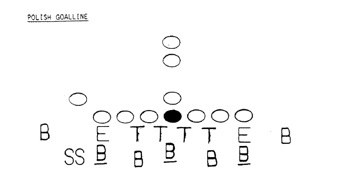

Although there was no indication that the Giants intentionally placed twelve players on the field[ref]Barry Petchesky, Did the Giants Put 12 Men on the Field on Purpose for Brady’s First Hail Mary?, Slate (Feb. 6, 2012, 1:36 PM), http://www.slate.com/articles/sports/sports_nut/features/2011/nfl_2011/super_bowl/giants_ patriots_super_bowl_did_new_york_put_12_men_on_the_field_on_purpose_for_brady_s_first_hail_mary_.html.[/ref]—and Figure 1 seems to show the twelfth man running toward the sideline to get off the field rather than trying to be involved in the play—one could see the wisdom of that strategy. Leading by more than three points, such that the opponent must score a touchdown to tie or win, and with the opponent far from the end zone in the waning seconds of the game, a team will gladly surrender five yards in exchange for running half the remaining time off the clock. In fact, one former NFL defensive coach designed a play for this very situation, shown in Figure 2. The play intentionally places as many as three extra defenders on the field, making it more likely the defense would stop whatever play the offense ran, while willingly accepting the penalty in exchange for time running off the clock.[ref]See Dom Cosentino, Buddy Ryan’s “Polish Goal Line” Defense Was Against the Rules, and That Was the Point, DeadSpin (Oct. 19, 2011, 4:55 PM), http://deadspin.com/5851460/buddy-ryans-polish-goal-line-defense-was-against-the-rules-and-that-was-the-point.[/ref]

Figure 2.

An intentional penalty in this game situation reflects all four of the features triggering a limiting rule.

First, the play produces a significant cost-benefit disparity in favor of the defending team holding a lead. From the defense’s perspective, the play runs time off the clock, while the extra defenders increase its chances of stopping the offense on the play. The defense does incur the cost of the five-yard penalty, but that is a minimal, virtually meaningless cost in this situation because the offense remains half a field from scoring the go-ahead touchdown and has much less time to do it. The trailing team on offense experiences this as high costs, offset by a minimal, virtually meaningless benefit—the five yards do not help the offense much, given the loss of time and the long distance still to travel for the touchdown. Rulemakers could rationally view the cost-benefit balance as sufficiently disparate to justify a limiting rule, given the relative meaninglessness of the five yards and the importance of the expired seconds.

Second, the defensive team is free to manipulate the play. It makes the choice to place those extra players on the field, and doing so gives it an overwhelming advantage in stopping the play by playing twelve or more players against eleven. The offense can do nothing to counter this move except run its play, which is unlikely to succeed against the extra defenders.

Third, the defense acts contrary to ordinary expectations in deliberately placing too many players on the field, knowing that doing so violates the rules and will result in a penalty. Teams generally do not want to take penalties, which disadvantage them and benefit the opponent. In this case, however, taking that penalty is the point.

Finally, a defensive team with a lead has a strong incentive to do this whenever a similar situation arises, because the likely benefits of more easily stopping the play with the extra players and running significant seconds off the clock substantially outweigh the minimal costs of five yards with the ball still far from the end zone.

A limiting rule thus is appropriate here to prevent, or at least disincentivize, the defense from intentionally placing too many players on the field in this game situation. With the purported lesson of Super Bowl XLVI in mind, the NFL’s rulemakers did just that. The new rule, which took effect in the 2012 season, created a new too-many-players penalty. If the defense has more than eleven players in its formation—meaning on the field and ready to be involved in the play—when the snap is imminent, the referees immediately whistle the play dead and call the infraction, stopping the clock and assessing five yards against the defense. This removes any incentive to intentionally play too many defenders. Because no time runs off the clock, the defense incurs only the cost of losing five yards without gaining the sought after benefit of lost time.

The incentive for a defensive team with a lead to place extra players in formation is not present in every late-game situation. For example, it likely would not do this if it was ahead by only three points or fewer and a field goal could tie or win the game because the five-yard penalty would shorten the length of the field goal, making it a meaningful cost to the defense and meaningful benefit to the offense. The defense also likely would not try this if more time remained on the clock. Wasting eight seconds on a nonplay is not significant with two minutes remaining because the offense has more time and more plays to move the ball down the field. Moreover, the defense likely would not try this if the ball is close to the end zone, in which case those five yards significantly increase the offense’s chances of scoring the winning touchdown.

This arguably renders the new dead-ball penalty overinclusive. The limiting rule applies whenever the defense has too many players in the formation, even if the infraction is obviously not intentional because the game situation is one in which the defense has no real incentive to take the penalty. But limiting rules, like most legislative rules, often are overinclusive, a byproduct of trying to regulate conduct with words.[ref]Wasserman, supra note 1, at 513.[/ref] And overinclusiveness becomes problematic only if the rule prohibits instances of the targeted conduct that, on balance, are beneficial to the game.[ref]Id. at 512–13.[/ref] But there are no beneficial examples of the defense placing too many players in formation—no situations in which it would be a net positive within the game’s logic and structure for a team to have twelve players involved in a play—that are lost by imposing a dead-ball penalty even if the defense does not act intentionally. To the extent the defense has no strategic incentive to intentionally take this foul in a particular game situation, the new dead-ball penalty offers a second disincentive against the defense ever doing it intentionally.

Moreover, the original too-many-players penalty, which is not a dead-ball penalty and does not immediately stop the clock, remains on the books. It controls when the extra players on the field are not involved in the play when the ball is snapped, usually when they are trying to run off the field but have not reached the sideline. While a penalty, this play remains live, with the clock stopping and the infraction called only after completion of the play.[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rule 5-1-1 (2013).[/ref] In cost-benefit terms, a dead-ball penalty is unnecessary here. Because the extra player is not in the formation and not involved in the play, the play itself remains eleven-on-eleven. The defense gains no extraordinary benefit from having extra players to stop the play and the offense has the same chance of running a successful play against an equal number of defenders. Absent that potential benefit, a defensive team would never intentionally commit this foul, so a limiting rule is not necessary as a deterrent.

2. Conserving Time Through Penalties

The flip side involves a trailing team without the ball seeking to preserve time through intentional penalties. The goal is to stop the clock, extend the game, and force the offense to run additional plays, thereby giving the trailing team a chance to get the ball back and win the game. One example—taken from a November 2013 regular season game—shows the welter of competing rules that respond to incentives and cost-benefit balances. It also shows the different approaches rulemakers may take to closing gaps in the rules.

With just over two minutes remaining in the second half, the New Orleans Saints led the Atlanta Falcons 17–13 and had possession of the ball. The Saints gained eighteen yards and a first down on a play in which the Falcons committed defensive holding, a foul penalized by five yards and an automatic first down. The Saints declined the penalty and accepted the result of the play, which gave them more yards than would the penalty. Had there been no foul, the clock would have continued to run. But the penalty stopped the clock, which would not restart until the next snap, functionally giving the Falcons an additional timeout. The clock stoppage forced the Saints to run several additional plays, plays they might not have had to run had the clock not stopped on the penalty. The Falcons got the ball back with five seconds remaining,[ref]4th Quarter Play by Play, ESPN NFL, http://scores.espn.go.com/nfl/playbyplay?gameId=331121001&period=4 (last visited Jan. 6, 2014).[/ref] time that would have been gone had there been no penalty.[ref]SlateRadio, Hang up and Listen: The King of the (Chess) World Edition, SoundCloud, https://soundcloud.com/slateradio/hang-up-and-listen-the-king-of (last visited Jan. 6, 2014). The relevant discussion begins at the 51:50 mark of the audio.[/ref]

Figure 3.

All four features are present in this game situation, making a limiting rule appropriate. First, the play produced a significantly inequitable cost-benefit disparity—the trailing defensive team stopped the clock when it otherwise could not have without having to spend a timeout, forced the leading team to run additional plays, and got the ball back with at least a few seconds remaining and a chance to win the game. Second, the defense controlled the play because the offense could do nothing to prevent the foul or the clock from stopping. Third, the trailing team again acted contrary to the game’s ordinary rules, practices, and strategies because teams ordinarily do not want to commit fouls or incur the costs of penalty yards. Finally, the opportunity to preserve time might incentivize a trailing defense to commit such fouls in similar situations.

This play sits at the intersection of three rules. The default rule is that when either team commits a foul, the clock restarts as if no foul had occurred. Thus, if the clock would have kept running at the end of the play but for the foul, the clock restarts as soon as the ball is ready, but if the clock would have stopped even without the foul, the clock restarts on the next snap.[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rule 4-3-2(f) (2013).[/ref] But this default rule does not apply in the last two minutes of the first half or the last five minutes of the second half, when the clock instead always restarts on the next snap.[ref]Id. at Rules 4-3-2(f)(1), (2).[/ref] This exception controlled in the Saints-Falcons because fewer than five minutes remained in the second half. This is why the penalty functioned as a timeout for the Falcons—although the clock ordinarily would not have stopped absent the foul, it did stop in the final five minutes. Third, in the final minute of each half, teams are prohibited from conserving time by committing certain acts, including intentional fouls that cause the clock to stop.[ref]Id. at Rule 4-7-1(f).[/ref] The penalty for such an act is that ten seconds run off the clock and the clock restarts when the ball is ready.

This third rule is a limiting rule. It closes a potential hole in the rules by imposing the outcome that would have resulted on the play without the intentional penalty, thereby putting the teams in the same place as if the penalty had not occurred—the clock restarts and the ten second runoff puts the time about where it would have been had there been no penalty and the clock continued running. By imposing that outcome, the limiting rule eliminates the incentive for the trailing team to intentionally commit penalties to stop the clock in the final minute.

But our game demonstrates that the limiting rule does not go far enough. It does not reach intentional fouls occurring with slightly more than one minute remaining in a half but late enough that the trailing team has the same incentives to conserve time. The limiting rule also does not address unintentional fouls—as this play might have been—meaning a trailing team might gain these significant cost-benefit advantages, even if only accidentally.

The solution is to extend the limiting rule in either of two ways. One way is to extend when the limiting rule applies, perhaps to the final three minutes of each half, or at least of the second half. By that point, a leading team is already in time-wasting mode and a trailing team in time-conserving mode, meaning the incentives to stop the clock by committing fouls remain. The increasing sophistication with which NFL coaches understand and strategize these final minutes[ref]Game situations and best strategies are regularly dissected on advanced metrics sites. Advanced NFL Stats, http://www.advancednflstats.com (last visited Jan. 6, 2014).[/ref]—suggests trailing teams will try to conserve time earlier than the one-minute mark.

A better option is to eliminate the intermediate exception in Rule 4-3-2(f)(2). Instead, the default rule—if the clock would have continued running on the last play but for the penalty, the clock restarts when the ball is ready—controls throughout the game until the final minute of each half, at which point the enhanced sanction of Rule 4-7-1 takes over. Teams thus never receive any time benefit even from an accidental penalty. The limiting rule is needed only for the narrower function of disincentivizing intentional fouls just in the final minute by imposing the additional cost of the ten-second run-off. This approach eliminates the current gap between the one minute mark when Rule 4-7-1 takes effect and the five minute mark when Rule 4-3-2(f)(2) take effect. And it ensures that trailing teams never gain substantial time benefits—the functional equivalent of a timeout—in the closing minutes by committing fouls, whether unintentionally or intentionally.

B. Intentional Scores and Intentional Nonscores

Football’s balance between points and time, and its effect on rules and strategy, was on even more vivid display on the Giants’ final scoring drive of Super Bowl XLVI, which immediately preceded the Patriots’ final drive on which the Giants committed the too-many players penalty.

With approximately one minute remaining in the game, the Patriots led 17–15 and the Giants had the ball on the Patriots’ six-yard line. The Giants were highly likely to score the go-ahead points, whether by touchdown[ref]A team with a first down from the opponent’s six yard line has a 68 percent likelihood of scoring a touchdown on the drive. Conor McGovern, A Closer Look at Touchdowns in the Red Zone, Football Outsiders, http://www.footballoutsiders.com/stat-analysis/2013/closer-look-touchdowns-red-zone (last visited Jan. 6, 2014).[/ref] or by a very short field goal.[ref]Had the Giants gained no more yards, this would have been a 23-yard field goal. During the 2012 regular season, NFL kickers were 15/15 on field goals of 1–20 yards (meaning the ball was snapped from the three-yard line or closer) and 231/239 on field goals of 20–29 yards (meaning the ball was snapped somewhere between the three and twelve yard lines). Sortable Stats, Yahoo! Sports, http://sports.yahoo.com/nfl/stats/bycategory?cat=Kicking&conference=NFL&year=season_2012&timeframe=All&sort=272&old_category=Kicking (last updated Jan. 5, 2014).[/ref] Recognizing this, the Patriots intentionally allowed the Giants to score a touchdown on the next play, allowing the Giants running back to run untouched into the end zone. The Patriots’ strategy was to allow the inevitable points quickly and get the ball back with more time left for its offense to move the ball and score.[ref]ByZirtrix, Super Bowl XLVI Bradshaw Game Winning Touchdown! Giants v Patriots (21-17), YouTube (Feb. 5, 2012), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWtQm0FXWr0.[/ref]

Figure 4.

This was not the first Super Bowl in which the defense allowed its opponent to score the winning points easily in order to maximize the amount of time remaining when it regained possession. In Super Bowl XXXII, played in January 1998, the game was tied 24–24 with less than two minutes remaining when the Denver Broncos had the ball on the Green Bay Packers’ one-yard line. Similarly recognizing the near-certainty that the Broncos would score some points to take the lead, the Packers allowed the Broncos to score the go-ahead touchdown on the next play, thereby giving the Packers the ball back with more time on the clock.[ref]Best Super Bowls of All-Time—Super Bowl XXXII—Green Bay Packers vrs. Denver Broncos, evonsports (Jan. 30, 2012), http://evonsports.wordpress.com/2012/01/30/best-super-bowls-of-all-time-5-super-bowl-xxxii-green-bay-packers-vrs-denver-broncos (“Packers’ coach Mike Holmgren instructed his team to let the Broncos score to preserve as much time on the clock for Favre to drive down the field.”).[/ref]

The offensive team, knowing it is highly likely to score to take the lead, especially if a short field goal is enough to win the game, may thwart the defense’s strategy by intentionally trying to not score quickly. The offense might run plays that will not score a touchdown or even advance the ball; the goal is simply to run time off the clock or force the defense to spend its limited timeouts before scoring those go-ahead points several plays, and seconds, later. When the opposing team gets the ball, now trailing, it has less time and fewer timeouts, which together make a game-winning drive more difficult.[ref]Especially if the team now trails by more than three points—as in both of our games—in which case it must move the ball all the way down the field for a touchdown.[/ref] Figure 4 shows that the Giants running back recognized that the defense was letting him score and tried to stop at the one-yard line, but his momentum carried him forward and he fell into the end zone.

Two of the defining features that trigger a limiting rule are present here: Both teams are intentionally failing, or declining, to make the ordinarily expected athletic plays and both have strong incentives to intentionally fail or decline to do so. The offense is intentionally not trying to score in an effort to run time off the clock, while the defense is intentionally allowing the offense to score in an effort to conserve time.

But the mutuality of these efforts (or nonefforts) eliminates the need for a limiting rule. This is not a one-sided situation in which one team acts contrary to expectations and the other is helpless to meaningfully respond. Both teams influence this play, each attempting to manipulate the situation to its advantage, and those competing efforts cancel one another out. And each team has the power to counter the other’s strategy. Knowing the defense is going to allow it to score, the offense may run plays designed to use time but not score. The defense can counter this move by pushing the offensive player into the end zone. More importantly, the defense will have a chance, however difficult or unlikely, to stop the offense when it finally does attempt to score the go-ahead points. Alternatively, the offense can accept the quick-and-easy score to seize the lead and then rely on its defense to stop the opponent from scoring when it gets the ball back, even though more time remains on the clock. In fact, the let-them-score strategy failed for the Packers in Super Bowl XXXII and the Patriots in Super Bowl XLVI. In both games, the team given the uncontested late-game touchdown prevailed when its defense stopped the opponent from scoring on the next possession.

This game situation entails a relatively equitable exchange of costs, benefits, and risks. In allowing the offense to score, the now-trailing team risks being unable to overcome those points, even with extra time. In refusing to accept the score or in intentionally delaying scoring, the other team risks forgoing easy points and failing when it finally attempts to score. Each team is trying to work the situation to its advantage based on some calculation of what gives it the best percentage chance to win. This is not the overwhelmingly unbalanced cost-benefit exchange that demands a limiting rule as a corrective.[ref]See Brian Burke, When to Intentionally Allow a TD When Tied, Advanced NFL Stats (Jan. 15, 2013), http://www.advancednflstats.com/2013/01/when-to-intentionally-allow-td-when-tied.html.[/ref]

Objections to these competing strategies sound not in fairness or equity—the concerns compelling most limiting rules[ref]Wasserman, supra note 1, at 486, 493.[/ref]—but aesthetics.[ref]Tim Keown, Unworthy End to Super Bowl XLVI, ESPN (Feb. 7, 2012), http://espn.go.com/espn/commentary/story/_/page/keown-120207/ahmad-bradshaw-uncontested-touchdown-undignified-way-end-super-bowl-xlvi (“It was not a proud or particularly dignified way to decide the Super Bowl.”).[/ref] It looks and feels contrary to the supposed ethos of sport. The defense should not intentionally allow the offense to score the winning touchdown in the Super Bowl. An offensive player, given the long-dreamed-of opportunity to score the winning touchdown in the Super Bowl, should not regret that he could not stop himself from crossing the goal line. It is artistically unappealing to see a player, on the verge of scoring the championship-clinching points, trying to stop and scoring only because his weight and momentum caused him to flop backward into the end zone.

Whether to accept these dueling strategies depends on how we understand what are expected actions in football. This, in turn, depends on how we define the purpose of football and the competing goals of scoring points and running time off the clock. If the latter goal is as important as the former, then these strategies are ineluctably part of a team’s successful approach to the game—surrendering or forgoing points in favor of clock benefits is a sound and expected strategy that the rules should accommodate. In fact, intentionally surrendering points or refusing to accept easy points is a common strategy in the waning seconds of other sports governed by a clock.[ref]Basketball presents some obvious examples. A team trailing late in the game will intentionally foul to stop the clock and give the leading team a chance to increase its lead by making free throws. The trailing team’s hope is that the player will miss one or both free throws and that it will get the ball back and score, eventually tying the game if this process happens enough times. A different question, which has been a subject of statistical analysis, is whether a team leading by three points late in the game should intentionally foul, potentially giving up two points on the made free throws, but preventing the opponent from shooting a game-tying three-point shot. See, e.g., John Ezekowitz, Up Three, Time Running out, Do We Foul? The First Comprehensive CBB Analysis, Harvard Sports Analysis Collective (Aug. 24, 2010), http://harvardsportsanalysis.wordpress.com/2010/08/24/intentionally-fouling-up-3-points-the-first-comprehensive-cbb-analysis; Ken Pomeroy, Yet Another Study About Fouling When up 3, Kenpom.com (Feb. 12, 2013), http://kenpom.com/blog/index.php/weblog/entry/yet_another_study_about_fouling_when_up_3. On the other hand, knowing that it needs three points to tie the game, the shooting team might intentionally miss the second free throw, hoping to get the rebound and score the tying basket. See Varun Iyengar, Men’s Basketball Wins 3OT Thriller at Midd., Amherst Student (Feb. 19, 2013, 11:06 PM), http://amherststudent.amherst.edu/?q=article/2013/02/19/men%E2%80%99s-basketball-wins-3ot-thriller-midd.[/ref] In any event, even if football rulemakers wanted to eliminate this strategy for aesthetic reasons, it is not clear how they could do so or what the resulting limiting rule might look like. It would be impossible to enforce a rule that requires officials to identify when the offense is not trying to score or when the defense is not trying to stop the offense from scoring.

C. Intentional Safety

In Super Bowl XLVII, played in February 2013, the Baltimore Ravens led the San Francisco 49ers 33–29 with eleven seconds remaining. They had the ball on fourth down at their own eight-yard line and were about to punt the ball away.

But a punt in this situation is risky, as the punter would be standing at the back of the end zone and facing pressure from rushing defenders. Several bad outcomes are possible here: (1) a blocked punt or fumbled snap recovered by the 49ers for a go-ahead touchdown; (2) a poor punt under pressure returned for the go-ahead touchdown; (3) a poor punt under pressure giving the 49ers the ball with only a short distance to travel for the winning touchdown. An average professional punt travels approximately forty-six yards from the line of scrimmage,[ref]Sortable Stats, Yahoo! Sports, http://sports.yahoo.com/nfl/stats/bycategory?cat=Punting &conference=NFL&year=season_2012&timeframe=All&qualified=1&sort=411&old_category=Punting (last updated Jan. 5, 2014).[/ref] although the heavy rush in this situation made it unlikely to be an average punt. The best-case scenario for the Ravens would have given the 49ers the ball around midfield, with time enough for them to attempt one or two deep throws to the end zone. Another possibility was a blocked punt or fumbled snap that the Ravens recovered or that traveled out of bounds in the end zone, resulting in a safety and two points for the 49ers.

Faced with these options, the Ravens chose to take that safety intentionally. The punter took the snap and ran around the back of the end zone with the ball for eight seconds before stepping out of bounds.[ref]Stanley Shipley, Super Bowl—Where’s the Holding Penalty?, YouTube (Feb. 4, 2013), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-C8NZU-EqI.[/ref]

Figure 5.

The Ravens willingly gave up two points, making the score 33–31. And they still had to kick the ball back to the 49ers, just as before the safety. But the kick was now done as a safety kick, a free kick following a safety;[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rule 6-1-1(b) (2013).[/ref] the Ravens would kick from the twenty yard line rather than the end zone, with no rush and no risk of a bad snap or block. This safety kick traveled sixty-one yards in the air, far longer than the average punt under pressure; was fielded around the 49ers’ twenty yard line; and was returned only to midfield as time expired. Even if time had not expired on the free kick, the 49ers would have had time to run only one more play from scrimmage, likely from worse field position than if the ball had been punted from the end zone.

At first glance, this situation might appear to warrant a limiting rule. Without question, the Ravens intentionally acted contrary to football expectations and strategies. The punter made no effort to perform his ordinary and expected skill—punting—but instead held the ball for several seconds before intentionally stepping out of bounds in his own end zone and surrendering two points. And this was the plan; the Ravens made no effort to do anything else. Further, the game situation produced high benefits for the Ravens and imposed high burdens on the 49ers, in turn incentivizing the Ravens to make this move. On fourth down in the waning seconds of a four-point game when the leading team already must punt ball away, the two points are not a significant cost to it or a significant benefit to the trailing team. By contrast, running eight seconds off the clock and being able to kick without pressure from the twenty yard line with just three seconds remaining both strongly benefit the leading team and disadvantage the trailing team. One might see this cost-benefit exchange as too imbalanced, as the trailing team loses badly on the exchange.

What is missing here is disparity in control over the play, because both teams had a change to influence the play and to counter the opposing team’s moves. The 49ers could have limited the time that elapsed—lessening the cost incurred—by tackling the punter or making him run out of bounds sooner. Seemingly unprepared for the Ravens’ move, they allowed 75 percent of the remaining time to run off the clock. Had they reached the punter more quickly, they might have regained possession with more time remaining.

More importantly, the 49ers had several ways to take advantage of the safety once they regained possession, now trailing by two points and needing only a field goal to win the game. First, they could have returned the free kick for a touchdown. Second, the returner could have called for a fair catch on the free kick, leaving the 49ers time to attempt a game-winning play from scrimmage, albeit from distance and with only time to run one play.[ref]Again, they could have given themselves more time, perhaps enough to run two plays, had they not allowed so much time to lapse on the safety.[/ref] Third, and most intriguing for scholars of obscure rules, the returner could have called for a fair catch to set up a fair-catch kick. This is a field goal attempt, which would have won the game, from the spot of the fair catch, attempted with no rush on the kick.[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rules 10-2-4(a), 11-4-3 (2013).[/ref] This is a vestigial rule, a throwback to the rugby elements of early football and the “goal from mark.”[ref]Barry Petchesky, The Rarest Play in the NFL, Slate (Feb. 4, 2013, 5:00 PM), http://www.slate.com/articles/sports/sports_nut/2013/02/fair_catch_kick_we_ca me_tantalizingly_close_to_seeing_the_rarest_play_in.html (internal quotation marks omitted).[/ref] Although this likely was not an option given how far the Ravens’ free kick traveled, it might have been possible on a shorter free kick. An NFL kicker can make a field goal from approximately seventy-five yards away—meaning the ball is kicked from the opposite thirty-five yard line—when not under pressure, particularly indoors.

In any event, it is enough that football’s rules provide meaningful, even if improbable, opportunities to counter the intentional safety. So long as the basic rules and strategies allow a team to do something in response to an unexpected play, there is no need for the protections of a limiting rule. Certainly the opportunities available to a team in the 49ers’ situation are more realistic than the Patriots trying to run a successful play against twelve or thirteen defenders. Each of these options is less favorable to the 49ers than a blocked punt or a chance to return a live punt kicked under pressure from the back of the end zone. But that is why the Ravens willingly took the safety. It provided benefits—in terms of field position for the free kick and the lapsed time—with fewer risks, while imposing costs on the opponent. But a limiting rule is not appropriate so long as the disadvantaged team retains some opportunities to counter a strategy and avoid that cost-benefit imbalance, even if those options all are suboptimal.

Of course, it appears from Figure 5 that the 49ers took so long to reach the punter on the safety, and the Ravens were able to run so much time off the clock, in part because the Ravens’ offensive line committed multiple illegal holds, none of which were called. The Ravens thus prevented the 49ers from countering their strategy on the safety in a way that violated football’s rules. Offensive holding in the end zone results in a safety,[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rule 11-5-1 (2013).[/ref] so the outcome on the play—two points for the 49ers followed by a Ravens safety kick—would have been the same had those holds been called. But holding is a live-ball foul, meaning play continues and the clock runs until the play is over.[ref]Id. at Rules 4-4(e), 12-1-3(c).[/ref] Thus, even had those holds been called, the eight seconds would have lapsed on the nonplay. A leading team in this situation thus has incentive to act contrary to the game’s expectations in a second way—not only to intentionally take the safety by running out of the end zone but also to intentionally commit fouls as a way to prolong the play for as long as possible.

This additional element arguably renders the cost-benefit exchange inequitable and imbalanced, as the trailing team cannot reasonably be expected to counter illegal plays. Rulemakers thus might consider a partial limiting rule by eliminating intentional fouls that expend extra time on the intentional safety. One possibility is to make holding in the end zone a dead-ball penalty, meaning that once the official identifies the hold, the whistle blows the play dead and stops the clock. This eliminates the incentive to commit the holding foul on top of the intentional safety. The leading team incurs the two-point cost of the safety without receiving the additional benefit of more time running off the clock. It also levels the cost-benefit balance somewhat, by preventing the leading team from unlawfully running additional time in the course of surrendering the safety. But this may not be a feasible or safe solution.[ref]See Wasserman, supra note 1, at 514–15.[/ref] It is difficult to stop the action midplay, as opposed to at or immediately after the snap, because players may not hear the whistle and may be moving too quickly to stop.

A more workable and safe limiting rule might restore the clock to the point at which the holding foul occurred. Based on the video of Super Bowl XLVII in Figure 5, this rule would have restored the clock to about ten seconds, when the first obvious hold occurred, meaning only one second would have lapsed on the safety and the 49ers might have had more time to do something following the free kick. This rule again eliminates any incentive to commit intentional holds by removing the additional timing benefit to the leading team and the additional timing cost on the trailing team.

One also might complain about cost-benefit imbalance if time expires on the safety itself while the leading team is running around the end zone—if, for example, there were only three seconds remaining at the beginning of the play. But existing rules address this potential disparity. If a safety occurs at the end of a half, the receiving team—the team that just scored two points—may elect to receive the free kick.[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rule 4-8-2(h) (2013).[/ref] A team trailing at the end of regulation obviously will do so. Further, if time expires on a free kick on which a fair catch is called, the team can extend time with a fair-catch kick, although not with another play from scrimmage.[ref]Id. at Rule 10-2-5(a).[/ref] In other words, following the safety, the trailing team will have a chance to receive the safety kick and try to either return it for a touchdown or attempt a fair-catch kick, even after time has expired. We might, however, question leaving the trailing team with only two options rather than three merely because time happened to expire on the safety. Rulemakers thus might restore a third option on an end-of-second-half, no-time-remaining safety—fair catch and one play from scrimmage—to further equalize the cost-benefit exchange.

D. Sideline Interference

The potential for unexpected strategy in Super Bowl XLVII between the Ravens and 49ers did not end with the intentional safety. As teams set up for the subsequent safety kick, the Ravens’ quarterback, Joe Flacco, was recorded on the sideline talking with teammates about running onto the field and tackling the 49ers returner if he broke free on the return and was about to score a touchdown.[ref]‘Sound FX’: Baltimore Ravens Win Super Bowl XLVII, NFL (Feb. 6, 2013, 9:35 PM), http://www.nfl.com/videos/nfl-films-sound-efx/0ap2000000136915/Sound-FX-Ravens-win-Super-Bowl-XLVII. Flacco can be heard from the 3:55–4:14 mark in the video.[/ref]

Flacco was threatening to repeat one of the most infamous plays in college football history. In the 1954 Cotton Bowl between the University of Alabama and Rice University, Alabama’s Tommy Lewis jumped off the bench to tackle Rice’s Dicky Moegle, who had broken a long run along the sideline.[ref]Ronstinetx, 1954 Cotton Bowl: Dicky Maegle—Tommy Lewis Tackle Play, YouTube (Jan. 1, 2008), http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=eSteCSinjTs; see also Dick Heller, Refs Didn’t Cotton to Off-Bench Stop, Wash. Times, Jan. 1, 2007, available at http://www.ricefootball.net/collegeinnwtstory.htm.[/ref]

Figure 6.

This game situation unquestionably demands a limiting rule because all four defining features are present. First, by jumping off the bench and interfering with an ongoing play, Flacco would intentionally be doing something entirely contrary to football’s ordinary expectations, rules, and practices. Second, there is nothing the trailing team can do to prevent him from doing this—no way to stop him from running off the bench and no way to counter the interference. Third, the benefits to be gained—stopping a certain, Super Bowl–winning touchdown—are obvious and overwhelming and clearly incentivize attempting this move. The game would not end on this foul,[ref]Nat’l Football League, Official Playing Rules of the National Football League Rule 4-8-2(a) (2013).[/ref] so the 49ers would get a chance to run an untimed play from scrimmage or kick the winning field goal following the penalty. Nevertheless, the cost-benefit exchange is heavily imbalanced. A player in Flacco’s position would much rather halt a certain score and take a chance that his defense could stop one play from scrimmage or that the opponent would miss the field goal attempt. Having an opportunity to defend a new play, even if unsuccessful, is better than watching a certain touchdown that clinches the Super Bowl. Similarly, the costs to the 49ers of losing a certain, game-winning score are much greater than the benefits of an opportunity to attempt a game-winning play against the defense.

Fortunately, the NFL has a limiting rule for such a situation. A player or anyone else on the bench may not “interfere with play by any act which is palpably unfair.”[ref]Id. at Rule 12-3-3.[/ref] The rule grants the referee discretion, after consulting with the other officials, to award a score rather than the ordinary distance penalty.[ref]Id.[/ref] In other words, had this play developed and Flacco done as he was threatening, the officials would have awarded the 49ers the game-winning touchdown that would have happened anyway. The officials similarly awarded a touchdown for the off-the-bench tackle in the 1954 Cotton Bowl.

This is precisely how a limiting rule should function. It imposes the outcome—a game winning touchdown—that would have resulted had Flacco not acted contrary to the game’s ordinary expectations, rules, ethics, and strategies by interfering with the play. And by imposing that outcome, the rule eliminates any incentive for him to do this. A player has no reason to interfere with the return if the touchdown will be awarded in any event. Of course, awarding the touchdown is discretionary—the official “may aware a score”—so the incentive is not eliminated entirely. Flacco recognized this, stating that the worst that could happen was that officials award the touchdown anyway. But if there is even a remote possibility that they would not, it might be worth the risk. The effectiveness of limiting rules in eliminating negative incentives thus depends not only on the rulemakers who draft the rules but also on the game officials who apply and enforce them.

Sideline interference returned to the public conversation during the 2013 regular season, ironically with the Ravens on the opposite side of the play. During a game between the Ravens and Pittsburgh Steelers on Thanksgiving night, a Ravens player lost a potential touchdown when the Steelers’ head coach—who, also ironically, is a member of the Competition Committee—appeared to step onto the field in front of the Ravens’ player as he ran along the sideline. This caused the player to break stride and change direction to avoid a collision, allowing him to be tackled from behind. Sports commentary immediately returned to Flacco’s plans for the final play of the Super Bowl nine months earlier.[ref]See, e.g., Mike Tomlin Intentionally Interfered, Flacco Says, CBC Sports (Nov. 29, 2013, 1:01 PM), http://www.cbc.ca/sports/football/nfl/mike-tomlin-intentionally-interfered-flacco-says-1.2445288.[/ref]

Figure 7.

No penalty was called on the play, likely because the officials did not see the interference. But the NFL reviewed the play after the game and fined the coach $100,000, while also leaving open the possibility of stripping the team of a pick in the next draft.[ref]Alan Robinson, Steelers Coach Tomlin Fined 0k by NFL, TribLIVE (Dec. 4, 2013, 11:30 AM), http://triblive.com/sports/steelers/5192070-74/tomlin-draft-steelers#axzz2mQHFQxKr.[/ref] Such league-imposed postgame individual sanctions provide additional deterrence against sideline interference and similar intentional unfair acts. A player should be less willing to consider leaving the bench to tackle the breakaway runner if the game-winning touchdown will be awarded anyway and he will be fined a substantial sum of money or suspended once the game ends. These supplementary individual penalties also deter a player from gambling on how the referee will exercise his discretion on the play, even on the final play of the Super Bowl.

Conclusion

This Essay is not intended as a comprehensive catalogue of football game situations and limiting rules. Rather, it shows with a few examples that football contains plays involving varied cost-benefit balances, as well as limiting rules designed and functioning much like the infield fly rule. What is missing is the same fascination that academics have long had with baseball. Perhaps it is time for scholars to turn our eyes to the football rulebook.