Introduction

In equity markets, speculators attempt to profit from changes in stock prices. One strategy for doing so is to obtain information earlier than other market participants and then profit as that information spreads and market prices adjust in response to that new information. The Rothschilds’ trading on the information of Wellington’s victory at Waterloo is a classic example of that strategy.1 Another strategy is to create market-moving news, whether true or false.2Speculators might also attempt to affect the underlying value of a company by altering the legal environment—for example, by pushing for legislation that would increase the profitability of a corporation’s business or reduce the value of its assets.

Speculators could also affect stock prices by challenging the validity of patents that a publicly traded company owns, a strategy that recent changes to the patent review process has potentially made more profitable. In 2015, the Coalition for Affordable Drugs (CFAD), a series of hedge funds managed by Kyle Bass, the head of Hayman Capital Management LP, challenged the validity of pharmaceutical corporations’ patents through a review process called inter partes review (IPR), under the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).3 As of October 2015, Bass has filed twenty-eight challenges against pharmaceutical patents and announced plans to challenge more before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).4 Bass explained that the purpose of his IPR challenges is to invalidate weak patents, which impose costs on consumers, and thereby make those drugs more affordable.5

Some pharmaceutical companies that own these patents have characterized Bass’s challenges as an investment strategy that abuses the IPR system to profit by affecting pharmaceutical companies’ stock prices. Celgene Corp. and Pharmacyclics Inc., among other companies, have asked the USPTO to dismiss Bass’s IPR challenges against their patents, arguing that those challenges are “an abuse of process.”6 In a motion for sanctions against the CFAD filed on July 27, 2015, Celgene alleged that “each CFAD entity’s sole purpose is to ‘benefit [Mr. Bass’s] investments’ by filing IPRs and profiting from resulting changes in stock prices.”7 The real parties in interest8 in the CFAD’s IPR challenges, including those against Celgene’s patents, are Hayman Credes Master Fund LP, Hayman Capital Management LP, IP Navigation Group LLC, other entities under Bass’s ownership, and Bass himself.9 Biogen Inc., another pharmaceutical company with patents that Bass has challenged, has demanded that Bass’s fund release documents that would shed light on whether Bass has shorted stocks of pharmaceutical companies in connection with the filing of IPR challenges.10

Bass has countered some of the criticism that the pharmaceutical companies launched against him. In a response to Celgene’s motion for sanctions, the CFAD argued that financial gain being a petitioner’s motive for filing an IPR challenge provides no basis for finding wrongful conduct.11 The CFAD stated that “Celgene’s motion . . . makes the curious argument that filing IPR petitions with a profit motive constitutes an ‘abuse of process.’ Yet at the heart of nearly every patent and nearly every IPR, the motivation is profit.”12 In response to Celgene’s accusation that the CFAD’s motives are not entirely “altruistic,” the CFAD answered: “That is a truthful irrelevancy. The U.S. economy is based largely on the notion that individual self-interest, properly directed, benefits society writ large.”13 The CFAD acknowledged that its “IPRs are part of its investment strategy” but that “it will only succeed by invalidating patents, which would serve the socially valuable purpose of reducing drug prices artificially priced above the socially optimum level.”14 The CFAD also argued that even if Bass were short selling patent holders’ stock for financial gain (as the press speculated), such an action would not constitute an abuse of process.15 The CFAD cited to the Securities and Exchange Commission, which has stated that short sellers who short companies with overvalued stock can actually add to stock pricing efficiency by informing the market of the true economic value of those companies.16

While PTAB has denied Bass’s first two challenges, as of September 2015,17 it has also denied Celgene’s motion to sanction Bass under the claim that Bass seeks to profit from his IPRchallenges.18 The PTAB stated that “[p]rofit is at the heart of nearly every patent and nearly every inter partes review. As such, an economic motive for challenging a patent claim does not itself raise abuse of process issues.”19 The PTAB further stated that a petitioner like Bass who has “no competitive interest in the patents [he] challenge[s] is allowed to file a petition under the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act.”20 The PTAB added that the purpose of the IPR process is not limited to providing a less costly alternative to litigation and that the system was “designed to encourage the filing of meritorious patentability challenges, by any person who is not the patent owner.”21

We do not address whether the short-selling strategy in which journalists speculated Bass was engaging would constitute market manipulation. Rather, we analyze the effect that Bass’s challenges had on the stock price of the pharmaceutical corporations that own the challenged patents. On the basis of the observed pattern of returns after a challenge, we find that the market reactions to Bass’s initial IPR petitions could have provided him with the opportunity to profit by shorting a stock and quickly closing out his position. We find, however, that after the initial few IPR challenges, subsequent challenges no longer provoked a strong response in the capital market. That muted response implies that a trading strategy based on short-term price reactions to an IPR challenge would not have been profitable after the initial few challenges. Furthermore, later challenges actually produced strong responses in the opposite direction of what the short selling hypothesis would predict—that is, later challenges produced statistically significant positive abnormal returns. The PTAB’s first two rulings on Bass’s challenges as of September 1, 2015 also induced statistically significant positive abnormal returns for the challenged patent holder Acorda Therapeutics. An analysis of additional PTAB rulings could reveal whether the price reaction is particular to the precedential value of the PTAB’s first ruling or the PTAB’s rulings will affect the returns of those companies Bass challenged.

Part I summarizes the history of the IPR and the purpose of its creation. Part II examines the descriptive statistics of the companies that held patents that Bass challenged through IPR. We present an event study framework to analyze the effect of Bass’s 2015 IPR challenges on the stock prices of the pharmaceutical companies with challenged patents. Part III presents the empirical results, explains the statistical significance of those results, and analyzes the implications of the market response to Bass’s IPR challenges. Part IV proposes potential lines of analysis of imminent challenges.

I. Inter Partes Review

In 2011, the U.S. Congress enacted the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act,22 which established the IPR procedure for challenging the validity of a patent before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).23 IPR enables one to “request to cancel as unpatentable [one] or more claims of a patent” based on obviousness or lack of novelty.24 Designed to be more efficient and less expensive than the existing inter partes reexamination procedure that it replaced,25 IPRs generally yield a final decision within fifteen months, on average, after the initial filing date.26

The IPR procedure thus provides the parties with a validity decision much sooner than the average of three years required for an inter partes reexamination27 or a typical litigation in a district court. Empirical evidence shows that the cost of an IPR is generally an order of magnitude less than the cost of a validity challenge through litigation.28 Furthermore, because of the relative expediency of decisions in IPRs, courts are more likely to grant a stay on parallel litigations involving the challenged patent until the IPR process finishes.29 IPR thereby reduces the parties’ litigation costs by obviating simultaneous proceedings before the PTABand the district court.30

The IPR procedure raised the standard for challenging a patent’s validity by requiring the PTABto institute only petitions that have a “reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail with respect to at least [one] of the claims challenged in the petition.”31 Whereas in the past, the PTAB instituted 95 percent of all petitions for inter partes reexamination,32 since the passage of the America Invents Act, the PTAB has instituted only about 80 percent of petitions for IPR,33 compared with 95 percent of petitions before 2011. Yet, in an IPR, the burden of proof that the petitioner bears is lower than in a district court.34 In an IPR, the petitioner has the burden of proving by a preponderance of the evidence that one or more claims of the patent in suit are invalid.35 In contrast, a court presumes the validity of a patent,36 and the alleged infringer then bears the burden of disproving by “clear and convincing evidence.”37

A study by law professors Brian Love and Shawn Ambwani found that, as of September 2014—in the first two years after the PTAB began to accept petitions for IPR38—petitioners had filed 1841 requests for review, of which 348 requests (or about 19 percent) had been resolved by then.39 Those 348 terminated petitions challenged 5045 patent claims in total, of which the PTAB found about 20 percent invalid (999 of the 5045 challenged claims).40

Economic theory predicts that the IPR process instituted under the America Invents Act is likely to increase the number of challenges to patent validity for at least two reasons. First, the reduction in litigation costs means that a smaller expected gain is required to make the validity challenge worthwhile.41 To the extent that the cost of a legal challenge is a fixed cost, a reduction in that cost should increase the number of potential challenges with expected positive net present value.

Second, a reduction in the time necessary to reach a decision on a patent challenge should increase the number of challenges. To the extent that legal costs are variable and increase with the length of a proceeding, a shorter proceeding will reduce those costs. In addition, a potential gain in the near future is more valuable than a potential gain in the distant future. Likewise, a successful challenge that reaches a decision more quickly is more harmful for a patent owner than a successful challenge that takes longer to resolve. That greater speed in deciding whether a challenged patent is valid implies that a challenge will create a greater change in the current share price of a publicly traded company that is the patent holder, even if the probabilities of success of inter partes review and inter partes reexamination are the same.

Thus, the reduction in the cost of challenging patent claims and the increased speed of the proceedings that result from the IPR process increased the opportunity for speculators to use that procedure to affect the share prices of the affected patent holders and to profit from trading.

II. Pharmaceutical Firms With Patents That Bass Has Petitioned for Inter Partes Review

To examine the effect that Bass’s IPR challenges have had on the patent holders’ share prices, we perform several tests. We first calculate three descriptive statistics on the companies whose patents Bass challenged. Those statistics are (1) the average percentage decline in share price after Bass filed an IPR challenge, (2) the overall dollar loss after Bass’s filing of a challenge, and (3) the percentage of market capitalization that the patent holder lost after the filing of a challenge. The percentage declines in stock price and market capitalization yield information on the extent to which an IPR challenge can diminish a company’s business prospects relative to the company’s other sources of value. The dollar decline in share price yields information on the size of the unleveraged return that a speculator could gain from filing an IPR challenge.

We next use a standard event study methodology to show that the announcement and filing of the IPR challenge was an actual market surprise. That is, we test whether the filing revealed new information to the market and caused investors to reevaluate their estimates of the patent holders’ value. We establish the statistical significance of the results with a t-test to determine if we can reject the null hypothesis that the abnormal stock returns on the event date are the same as during the 100 trading days before the event. Researchers have recently questioned whether this statistic is the appropriate test for single-stock, single-event studies. To address this concern we also implement the SQ Test proposed by Gelbach, Helland, and Klick that tests where the abnormal returns on the event date would rank as a quantile of all of the abnormal returns.42 We also directly test how many standard deviations of abnormal returns the abnormal returns on the event date are away from the average return. Our findings do not change when we use these alternative statistical tests. We use the dates on which Bass filed challenges against twelve patents for IPR and on which media outlets released news about those challenges to the markets.43

The market capitalizations of the companies that own the challenged patents range from $216 million to $229.8 billion at the time of the IPR filing, and those companies employ between 12 and 88,509 employees. The price-to-sales ratio—that is, the market capitalization, or the presumed price of purchasing all of the shares of the company, divided by the company’s yearly sales—of the challenged companies is high relative to other pharmaceutical companies. The ratio ranges from 3.42 to an outlier value of 112.99 and has a median value of 8.66. In contrast, the average price-to-sales ratio for publicly traded U.S. pharmaceutical companies is 4.33.44 The high price-to-sales ratio might have been a factor in Bass’s identification of which companies to challenge, although the first two companies challenged, Acorda and Shire, have ratios below the industry average. The shares of companies with higher price-to-sales ratios cost more to purchase for a given dollar of sales. One company could have a higher price-to-sales ratio than another company because the first company earns a higher profit margin on its sales or because investors expect its sales to increase. The average age of the challenged patents at the time of the filing of the petition for IPR is 9.15 years, and the age of those patents range from 1.18 years to 20.0 years. The table in Appendix 1 reports the patents that Bass has challenged and the summary statistics of the companies that own the challenged patents.

Although Bass’s initial challenges had a statistically significant negative effect on the share price of the holder of the challenged patents, the effect of the challenges on the stock prices appears to have waned over time. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the relevant pharmaceutical companies’ stock performances on the reporting date of the IPR challenge.

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics of Stock Performance on the Reporting Date of the Patent’s IPR Challenge45

| Company Name | Stock Exchange |

Outstan-ding Shares (Millions) | Date of IPR Filing(2015) |

Percen-tage Change in Price on Date of IPRFiling (%) | Losses Upon IPRFiling ($ Millions) |

Date of News of IPRFiling Within 3-Days (2015) |

Percentage Change in Price on Date of News (%) | Losses Upon News of Filing ($ Millions) |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

NASDAQ | 41 | Feb. 10* | -9.65%* | -$4.11* | Feb. 10 | -9.65% | -$3.97* |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

NASDAQ | 41 | Feb. 27* | -4.84%* | -$2.06* | Feb. 27 | -4.84% | -$1.99 |

| Shire, Inc. | NASDAQ | 587 | Apr. 1 | -2.71% | -$5.40 | Apr. 2 | -2.54% | -$14.90 |

| Jazz Pharma. | NASDAQ | 61 | Apr. 6 | -0.59% | -$0.36 | Apr. 7 | 0.54% | $0.33 |

| Pharma cyclics |

NASDAQ | 76 | Apr. 20* | -0.34%* | -$0.26* | Apr. 20 | -0.34% | -$0.26 |

| Biogen IDEC Int’l |

NASDAQ | 235 | Apr. 22* | 0.35%* | $0.81* | Apr. 22 | 0.35% | $0.81 |

| Shire/NPS. Pharma | NASDAQ | 587 | Apr. 23* | 0.071%* | $1.41* | Apr. 23 | 0.071% | $4.17 |

| Celgene Corp. | NASDAQ | 799 | Apr. 23* | 0.48%* | $3.78* | Apr. 23 | 0.48% | $3.80 |

| Biogen IDEC Int’l |

NASDAQ | 235 | May 1* | 3.29% | $7.73 | May 1 | 3.29% | $7.73 |

| Celgene Corp. | NASDAQ | 799 | May 7* | 3.09%* | $2,450* | May 7 | 3.09% | $2,471 |

| Pozen Inc. | NASDAQ | 32 | May 21* | 0.30%* | $0.07* | May 21 | 0.30% | $0.097 |

| Pozen Inc. | NASDAQ | 32 | June 8* | 18.94%* | $6.14* | June 8 | 18.94% | $6.13 |

| Pozen Inc. | NASDAQ | 32 | Aug. 7 | -6.26% | -$2.03 | - | - | - |

| Horizon Pharma. |

NASDAQ | 151 | Aug. 12 | -0.82% | -$1.31 | - | - | - |

| Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. | NASDAQ | 1,667 | Aug. 13 | 0.05% | $0.80 | - | - | - |

| Anacor Pharma., Inc. |

NASDAQ | 39 | Aug. 20 | -2.25% | -$0.99 | Aug. 21 | 0.92% | $0.36 |

| Hoffmann-La Roche | OTC | 851 | Aug. 22 | -0.59% | -$5.00 | Aug. 25 | 0.21% | $1.76 |

| Insys Pharma, Inc. | NASDAQ | 72 | Aug. 24 | -4.12% | -$2.96 | Aug. 25 | 4.14% | $2.96 |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

NASDAQ | 42 | Sep. 2 | 2.49% | $1.07 | Sep. 4 | –0.47% | –$0.20 |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

NASDAQ | 42 | Sep. 3 | –2.15% | –$0.92 | Sep. 4 | –0.47% | –$0.20 |

| Biogen IDEC Int’l |

NASDAQ | 235 | Sep. 28* | 4.39% | $10.80 | Sep. 28 | 4.39% | $10.80 |

As Table 1 reports, there was a decline in the stock price of the patent holding companies whose patents Bass challenged at the end of August 2015 within the one-day window of the IPR challenge. That decline, however, coincided with a widespread price decline in worldwide stock markets. To examine the relative impact of Bass’s IPR challenges, one must disaggregate the impact of broad market decline on the stock of the patent holding company from that of Bass’s IPR challenges.

We use the S&P 500 Index, which includes the 500 most widely held stocks on the New York Stock Exchange, as a proxy for the performance of the entire U.S. stock market.46 We also use the NYSE Arca Pharmaceutical Index (DRG), which represents a cross section of highly capitalized pharmaceutical firms, as a proxy for the market performance of the pharmaceutical sector.47 Those two indices show fairly steady returns from February through June 2015 until there was an increase in market volatility and broad market declines at the end of August 2015. That the market volatility increased toward the end of the period of study further highlights the limited reliability of the absolute stock performance of companies with challenged patents.

We find that the daily returns of the challenged companies indicate that the first three filings of IPR petitions resulted in statistically significant negative returns for the holders of the challenged patents on the day of filing, but the next few filings did not result in negative returns. Celgene Corp. actually experienced positive returns on the days on which Bass filed its IPR challenges. That pattern contradicts the expectation that Bass’s IPR filings would lower the stock prices of the holders of the challenged patents, given that an IPR challenge potentially puts shareholders at risk of losing the value of their intellectual property.

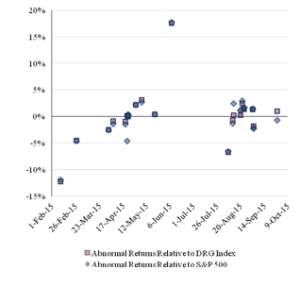

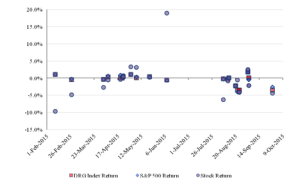

Figure 1 shows the daily percentage return of the stocks of patent holders on the date that the media reported that Bass had filed a challenge against their patents. (In some cases, the news that Bass had filed a challenge was not reported until the day after the filing.) Figure 1 also shows the daily returns of the patent holders’ stocks on the reporting dates of the S&P 500 Index and the DRG Index.

Figure 1: The Daily Percentage Return on the Reporting Date ofthe Patent Challenge

A more sophisticated analysis would examine the performance of the stock of each challenged company relative to its predicted performance rather than examining the absolute performance of the stock. Such an analysis would account for the systematic effects that might affect many securities and reveal the abnormal price change in a particular stock. In Part III, we conduct such analysis of the IPR challenges. We examine the cumulative abnormal returns of companies with challenged patents by comparing the actual performance of their stock relative to the expected performance that one would predict on the basis of the historical sensitivity of each company’s stock to the stock market indices.

III. The Abnormal Returns of Companies Holding Patents That Bass Challenged

The nominal change in stock prices is useful as a first-pass measure of stock performance. Still, an accurate assessment of the effect of new information requires an analysis of a stock price’s performance relative to its expected performance. For example, a fund manager could provide his clients positive returns every year, but if his fund performance lags behind the performance of a benchmark market index, then he is not successful in his goal of adding value for investors. Similarly, one must judge a stock’s performance relative to its expected performance, not simply on whether the stock had a nonzero return.

We determine the relative change in the stock prices of the holders of the challenged patents using an event study framework. We determine a stock’s expected returns using the stock’s short-term historical performance relative to a market index. If a stock’s price is expected to increase when the broader stock market index increases, then even an increase in the stock’s price could represent relative underperformance if the stock did not meet its expected performance goals. That is, the effect of negative information might not be a decline in the stock’s price, but rather an increase in price that is less than what the stock should have achieved, given the broader market performance.

We examine both single-day and three-day event windows to calculate abnormal returns and thereby analyze the effect of the IPR filing on the patent-holding company’s share price relative to its predicted return, calculated on the basis of the performance of market indices. For example, a one-day event window examines the stock’s returns only on the day that either Bass or the media reported the IPR filing. The three-day event window also includes the day before the filing announcement and the day after the announcement. The three-day window can capture cumulative abnormal returns owing to information that is leaked before the public announcement or because of the residual effects of the announcement. For example, if the announcement of the IPR filing was made late in the trading day (or after the close of trading) and if the price did not fully reflect all of the abnormal return until the next trading day, then the three-day event window would capture the abnormal returns from the announcement to a greater extent than a one-day event window. For example, Bass filed its IPR challenge against Jazz Pharmaceutical’s U.S. Patent No. 7,895,059 on April 6, 2015, but the business press did not report the filing until April 7, 2015.48 The three-day event window will capture the effect of that delay on Jazz Pharmaceutical’s share price, whereas a single-day event window might not.

We apply the same methodology to estimate the cumulative abnormal returns of the company holding a challenged patent on the day that the PTAB released its decision on Bass’s IPRchallenge against its patent. We examine cumulative abnormal returns for both the single-day and three-day event window. That the PTAB has ruled on only two of Bass’s petitions as of October 7, 2015 limits our analysis. Yet, as the PTAB decides on additional cases, one can apply the existing framework to incorporate that data.

Table 2 reports the results of the one-day and three-day event studies. The relative, abnormal returns display a similar pattern to the nominal stock returns. Table 2 also shows the cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) and the standard deviations relative to the S&P 500 Index.

Table 2: Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR) of the Challenged Companies Relative to the S&P 500 Index49

| Event Chal-lenge # | Company | Event Date | 1-Day CAR(%) | Stan- dard Devia-tion of Resid-uals |

T-Statistic | SQ Test | 3-Day CAR(%) | Stan- dard Devia- tion of Resi-duals |

T-Statistic | SQ Test |

| 1 | Acorda Therapeutics |

Feb. 10, 2015 | –11.94% | 3.22% | –3.67 | 99 | –10.78% | 5.58% | –1.82 | 97 |

| 2 | Acorda Therapeutics |

Feb. 27, 2015 | –4.63% | 2.41% | –1.91 | 97 | –2.98% | 4.17% | –0.70 | 83 |

| 3 | Shire, Inc. | Apr. 2, 2015 | –2.59% | 1.56% | –1.65 | 91 | –6.19% | 2.70% | –2.27 | 77 |

| 4 | Jazz Pharma. | Apr. 7, 2015 | –1.41% | 1.53% | –0.91 | 63 | –2.40% | 2.68% | –0.88 | 48 |

| 5 | Pharmacyclics | Apr. 20, 2015 | –1.46% | 2.98% | –0.48 | 70 | –1.73% | 5.20% | –0.32 | 27 |

| 6 | Biogen IDEC Int'l |

Apr. 22, 2015 | –4.64% | 2.18% | –0.21 | 21 | 0.19% | 3.77% | 0.05 | 19 |

| 7 | Shire/NPS. Pharma. | Apr. 23, 2015 | 0.35% | 1.71% | 0.20 | 17 | 0.83% | 2.96% | 0.28 | 18 |

| 8 | Celgene Corp. | Apr. 23, 2015 | 0.20% | 1.65% | 0.12 | 17 | 2.20% | 2.85% | 0.76 | 8 |

| 9 | Biogen IDEC Int'l |

May 1, 2015 | 2.15% | 2.25% | 0.94 | 81 | 0.05% | 3.89% | 0.01 | 55 |

| 10 | Celgene Corp. | May 7, 2015 | 2.68% | 1.66% | 1.60 | 88 | 3.91% | 2.87% | 1.35 | 74 |

| 11 | Pozen Inc | May 21, 2015 | 0.36% | 2.65% | 0.13 | 22 | 1.45% | 4.59% | 0.31 | 12 |

| 12 | Pozen Inc | June 8, 2015 | 17.69% | 2.60% | 6.73 | 100 | 14.31% | 4.88% | 2.45 | 99 |

| 13 | Pozen Inc | Aug. 7, 2015 | –6.59% | 3.72% | –1.76 | 94 | –14.95% | 6.42% | –2.32 | 78 |

| 14 | Horizon Pharma. |

Aug. 12, 2015 | –1.32% | 2.98% | –0.44 | 44 | –3.04% | 5.16% | –0.59 | 27 |

| 15 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Aug. 13, 2015 | 2.43% | 1.15% | 0.21 | 20 | 0.52% | 2.01% | 0.26 | 8 |

| 16 | Anacor Pharma. |

Aug. 20, 2015 | 1.14% | 4.96% | 0.22 | 37 | 7.91% | 8.60% | 0.70 | 24 |

| 17 | Hoffman- La Roche |

Aug. 24, 2015 | 2.97% | 0.99% | 2.64 | 98 | 4.72% | 1.73% | 2.09 | 92 |

| 18 | Insys Pharma. | Aug. 24, 2015 | 1.65% | 2.93% | 0.50 | 49 | 13.74% | 5.04% | 2.36 | 42 |

| 19 | Acorda Therapeutics |

Sept. 2, 2015 | 1.42% | 2.13% | 0.65 | 57 | 0.40% | 3.70% | 0.10 | 33 |

| 20 | Acorda Therapeutics | Sept. 3, 2015 | –2.22% | 2.13% | –1.04 | 76 | –0.34% | 3.70% | –0.09 | 49 |

| 21 | Biogen IDECInt'l | Sept. 28, 2015 | –0.75% | 2.86% | –0.25 | 46 | –1.30% | 4.94% | –0.25 | 27 |

For each company with a challenged patent, the cumulative abnormal returns indicate the sum of the differences between the actual returns and the predicted returns over a one-day or three-day window. We calculate predicted returns for each company by regressing its stock’s daily returns on the market indices’ daily returns for the 100 trading days before the event window. The standard deviation of the abnormal returns defines the expected distribution of the abnormal returns. We calculate the standard error of cumulative abnormal returns during the event window and present the t-statistic to test the cumulative abnormal returns for statistical significance.

The results indicate that the expected negative abnormal returns only consistently occur for the first three challenges, and the later challenges have inconsistent effects. The first three IPR challenge events to patents held by Acorda Therapeutics and Shire Inc. had a statistically significant negative effect on share prices on the day of the event, although the third challenge event was statistically significant only at the 10 percent level. The abnormal returns for the next eight challenge events were not statistically significant for either the one or three-day event windows. Although the abnormal returns for the fourth, fifth, and sixth challenge events were not statistically significant, they were negative. The abnormal returns for the seventh through the eleventh challenge events were positive. The abnormal returns following the twelfth challenge event against Pozen’s patent on June 8, 2015 were both positive and statistically significant for both the one-day event window and the three-day event window. Bass’s third challenge against Pozen’s patent was the last challenge that was both statistically significant and had negative cumulative abnormal returns, although the single-day returns were statistically significant only at the 10 percent level. The thirteenth challenge, against Horizon Pharma, showed negative abnormal returns, but those returns were not statistically significant. The fourteenth and fifteenth challenges were not statistically significant, but they again showed positive abnormal returns.

The sixteenth challenge against Hoffmann-La Roche’s patent on August 24, 2015, also displayed positive cumulative abnormal returns, but the returns were statistically significant for both the one-day and three-day event windows. Bass’s challenge against Insys Pharma’s patents coincided with positive cumulative abnormal returns that were statistically insignificant for the one-day window but were statistically significant for the three-day window. The abnormal returns on August 24, 2015 could be less informative of the effect of Bass’s challenges, however, because of the increased volatility in the stock markets during that period. On August 24, 2015, the S&P 500 Index had its worst performance since 2011, formally moving into “correction” mode—that is a 10 percent or more price decline to adjust for an overvaluation—after steep declines in Asian and European stock markets.50 Hence, that Hoffmann-La Roche’s and Insys Pharma’s stock prices had positive returns relative to the S&P 500 on August 24, 2015, might explain less of the effect of Bass’s challenges than the cumulative abnormal returns that we analyze before August 2015. The next three challenge events against Acorda Therapeutics on September 2, 2015, and September 3, 2015, and against Biogen on September 28, 2015, did not result in statistically significant abnormal returns.

We also calculate the cumulative abnormal returns of the companies whose patents Bass challenged relative to a market index that tracks performance of stocks in the pharmaceutical industry. Table 3 reports the cumulative abnormal returns relative to the DRG Index, an index designed to represent a cross section of highly capitalized pharmaceutical firms.

Table 3: Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR) of the Challenged Companies Relative to the DRG Index51

| Event Chal-lenge Number | Company | Event Date | 1-Day CAR(%) | Stan- dard Devia-tion of Resid-uals |

T-Statistic | SQ Test | 3-Day CAR(%) | Stan- dard Devia- tion of Resid-uals |

T-Statistic | SQ Test |

| 1 | Acorda Therapeutics |

Feb. 10, 2015 | –12.30% | 3.16% | –3.84 | 99 | 10.97% | 5.48% | –1.87 | 97 |

| 2 | Acorda Therapeutics |

Feb. 27, 2015 | –4.50% | 2.40% | –1.87 | 98 | –2.95% | 4.42% | –0.69 | 80 |

| 3 | Shire, Inc | Apr. 2, 2015 | –2.49% | 1.44% | –1.72 | 92 | –4.97% | 2.50% | –1.97 | 79 |

| 4 | Jazz Pharma. | Apr. 7, 2015 | –0.89% | 1.53% | –0.58 | 49 | –2.53% | 2.70% | –0.93 | 31 |

| 5 | Pharmacyclics | Apr. 20, 2015 | –1.00% | 2.93% | –0.33 | 45 | –2.35% | 5.08% | –0.46 | 15 |

| 6 | Biogen IDEC Int'l |

Apr. 22, 2015 | 0.13% | 2.18% | 0.06 | 6 | –0.31% | 3.77% | –0.08 | 1 |

| 7 | Shire/ NPS. Pharma |

Apr. 23, 2015 | 0.14% | 1.57% | 0.09 | 7 | 1.44% | 2.71% | 0.53 | 5 |

| 8 | Celgene Corp. | Apr. 23, 2015 | –0.07% | 1.42% | –0.05 | 9 | 3.05% | 2.45% | 1.23 | 3 |

| 9 | Biogen IDEC Int'l |

May 1, 2015 | 2.14% | 2.21% | 0.96 | 81 | –0.02% | 3.83% | –0.01 | 61 |

| 10 | Celgene Corp. | May 7, 2015 | 3.10% | 1.43% | 2.15 | 99 | 3.98% | 2.46% | 1.59 | 85 |

| 11 | Pozen Inc | May 21, 2015 | 0.38% | 2.67% | 0.14 | 21 | 1.47% | 4.63% | 0.32 | 13 |

| 12 | Pozen Inc | June 8, 2015 | 17.53% | 2.62% | 6.63 | 100 | 14.28% | 4.95% | 2.42 | 99 |

| 13 | Pozen Inc | Aug. 7, 2015 | –6.71% | 3.74% | –1.79 | 94 | –14.11% | 6.45% | –2.16 | 80 |

| 14 | Horizon Pharma. |

Aug. 12, 2015 | –0.73% | 3.01% | –0.24 | 22 | –2.90% | 5.21% | –0.56 | 14 |

| 15 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Aug. 13, 2015 | 0.22% | 1.06% | 0.20 | 28 | 1.18% | 1.86% | 0.63 | 6 |

| 16 | Anacor Pharma. |

Aug. 20, 2015 | 0.22% | 5.01% | 0.04 | 4 | 3.85% | 8.68% | 0.35 | 5 |

| 17 | Hoffman- La Roche |

Aug. 24, 2015 | 2.42% | 0.95% | 2.34 | 97 | 3.47% | 1.68% | 1.76 | 90 |

| 18 | Insys Pharma. |

Aug. 24, 2015 | 1.31% | 2.83% | 0.43 | 40 | 12.27% | 4.90% | 2.27 | 29 |

| 19 | Acorda Therapeutics |

Sept. 2, 2015 | 1.30% | 2.11% | 0.60 | 54 | 0.53% | 3.66% | 0.14 | 34 |

| 20 | Acorda Therapeutics |

Sept. 3, 2015 | –1.86% | 2.11% | –0.88 | 71 | –0.04% | 3.66% | 0.00 | 44 |

| 21 | Biogen IDEC Int'l |

Sept. 28, 2015 | 0.99% | 2.74% | 0.34 | 59 | 3.40% | 4.76% | 0.71 | 29 |

The results in Table 3 are similar to the cumulative abnormal returns relative to the S&P 500 Index. The first three challenge events show negative and abnormal returns for the companies that own challenged patents, although the single-day returns for the second and third challenge events were statistically significant only at the 10 percent level. Only the first challenge event was statistically significant for the three-day window. The abnormal returns for the fourth and fifth challenge events are also negative, but not statistically significant. Biogen’s abnormal returns on the days of the sixth and ninth IPR challenge events were positive, but negative for the three-day event window. None of these cumulative abnormal returns were statistically significant. The abnormal returns for the seventh and eighth challenge events were also not statistically significant. The positive cumulative abnormal returns for Celgene on the day of the tenth challenge event were statistically significant, although the three-day abnormal returns were not statistically significant. The challenges against Pozen’s patents on June 8, 2015, and August 7, 2015, had statistically significant effects on its stock returns, although the challenge against the same company’s patent on May 21, 2015, did not have a statistically significant effect on returns. Of the challenge events against Pozen, only the abnormal returns for the August 7, 2015, challenge were negative.

Bass’s challenges filed on August 24, 2015, resulted in statistically significant abnormal returns relative to the DRG Index that were positive. The challenge against Hoffmann-La Roche’s patent had a statistically significant positive effect on its stock returns over both the one-day and three-day event windows, although the abnormal returns over the three-day window are statistically significant only at the 10 percent level. The challenge against Insys Pharma had positive abnormal returns that were statistically insignificant over the one-day event window but statistically significant over the three-day event window. Similar to the returns relative to the S&P 500 Index, the patent holders’ returns relative to the DRG Index could be capturing more of the effect of market-wide volatility around August 24, 2015, and less of the effect of Bass’s challenges. None of the challenges in September 2015 had statistically significant abnormal returns relative to the DRG Index.

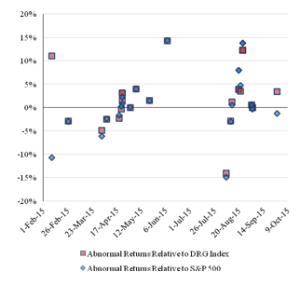

Figure 2 reports the pattern over time of the one-day abnormal return for each company owning a challenged patent. A blue diamond indicates the abnormal return relative to the S&P 500 Index, and an orange square indicates the abnormal return relative to the DRG Index.

Figure 2: One-Day Abnormal Returns for the ChallengedCompanies Over Time

The abnormal returns of each company that owns a challenged patent are similar for each index and show the same pattern. The initial IPR challenges produced negative abnormal returns, but later challenges do not show a clear trend and are contemporaneous with both positive and negative abnormal returns.

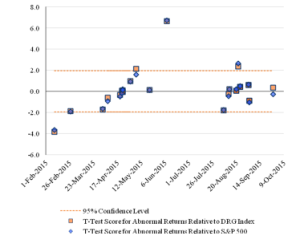

Figure 3 reports the pattern over time of the t-statistics for the one-day abnormal returns of the challenged companies with lines at the 5 percent level of statistical significance.

Figure 3: Statistical Significance of One-Day Abnormal Returnsfor the Challenged Companies Over Time

The lines drawn at the values 1.96 and -1.96 mark the boundaries of statistical significance at the 95 percent confidence level. Three of the IPR challenges were statistically significant at that level relative to the S&P 500 index, and four were statistically significant relative to the DRG index.

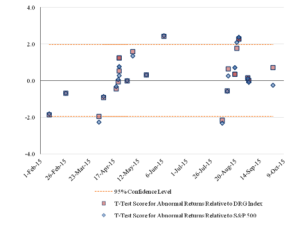

Figure 4 reports the pattern over time of the cumulative abnormal returns of the challenged companies for the three-day event window.

Figure 4: Three-Day Abnormal Returns for the ChallengedCompanies Over Time

There is a greater disparity among the companies in the cumulative abnormal returns for the three-day event window, but there is not a substantial difference. Similar to the results of the event study using a one-day event window, the event study using a three-day event window indicates negative abnormal returns for the early challenges and no clear trend in the abnormal returns for the later challenges.

Figure 5 reports the pattern over time of the statistical significance of the cumulative abnormal returns, as determined by the calculated t-statistics.

Figure 5: Statistical Significance of Three-Day CumulativeAbnormal Returns for the Challenged Companies Over Time

There are differences between the results using the one-day event window and the results using the three-day event window. The second event corresponds to a statistically significant, negative effect with a one-day event window but not with a three-day window. The challenge against Celgene made on May 7, 2015, is statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level relative to the DRG Index for the one-day event window and not for the three-day window and is not statistically significant for either window relative to the S&P 500 Index. The challenge event against Insys on August 24, 2015, had statistically insignificant results for the one-day event window relative to the S&P 500, but had statistically significant results for the three-day window.

We also calculate the abnormal returns on the day that the PTAB issued its decisions on Bass’s IPR petitions. On August 24, 2015, the PTAB denied the institution of Bass’s IPR petition against Acorda’s patent filed on February 10, 2015, and February 27, 2015. We find no statistically significant cumulative abnormal returns relative to the S&P 500 Index in the one-day event window following the PTAB’s ruling on Acorda’s patents on August 24, 2015, but we do find that Acorda had statistically significant positive returns relative to the S&P 500 Index (of 18.2 percent) over the three-day event window. On September 2, 2015, the PTAB denied the institution of Bass’s IPR petition against Biogen’s patent filed on May 1, 2015. We find no statistically significant cumulative abnormal returns relative to the S&P 500 Index in either the one-day event window or three-day event window following the PTAB’s ruling on Biogen’s patent. Table 4 summarizes the cumulative abnormal returns of Acorda and Biogen relative to the S&P 500 Index following the PTAB’s decisions on Bass’s challenges against Acorda and Biogen’s patents.

Table 4: Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR) Relative to theS&P 500 Index of the Challenged Companies After the PTAB’sRuling

| Company | Date of PTABDecision | 1-Day CAR(%) | Standard Deviation of Residuals | T-Statistic | SQ Test | 3-Day CAR(%) | Standard Deviation of Residuals | T-Statistic | SQ Test |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

Aug. 24, 2015 | 0.37% | 1.90% | 0.20 | 9 | 18.2% | 3.14% | 5.00 | 44 |

| Biogen IDECInt'l | Sept. 2,2015 | 1.55% | 2.88% | 0.53 | 75 | 3.90% | 4.97% | 0.77 | 39 |

We find that the Acorda’s cumulative abnormal returns relative to the DRG Index over the one-day and three-day event window are similar to its cumulative abnormal returns relative to the S&P 500 Index. Acorda did not have statistically significant abnormal returns relative to the DRG Index in the one-day event window following the PTAB’s decision on August 24, 2015, against Bass’s IPR challenge, but it did have statistically significant positive cumulative abnormal returns for the three-day event window. Biogen did not have statistically significant abnormal returns relative to the DRG index when the PTAB ruled against Bass’s challenge on September 2, 2015.

Table 5: Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR) Relative to theDRG Index of the Challenged Companies After the PTAB’sRuling

| Company | Date of PTABDecision | 1-Day CAR(%) | Standard Deviation of Residuals | T-Statistic | SQ Test | 3-Day CAR(%) | Standard Deviation of Residuals | T-Statistic | SQ Test |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

Aug. 24, 2015 | 0.08% | 1.86% | 0.04 | 3 | 16.6% | 3.08% | 5.64 | 30 |

| Biogen IDECInt'l | Sept. 2,2015 | 1.42% | 2.83% | 0.49 | 70 | 4.12% | 4.88% | 0.83 | 38 |

The PTAB has issued decisions on only three of Bass’s IPR challenges against pharmaceutical companies’ patents as of October 7, 2015, and these decisions were issued on only two days. Our results indicate that, whereas the PTAB’s first decision with respect to Bass’s petitions against Acorda induced statistically significant positive cumulative abnormal returns over the three-day window for the company holding the challenged patent, the PTAB’s subsequent decision regarding Bass’s petition against a patent of a different company did not result in statistically significant positive abnormal returns in either the one-day or three-day window. Although the sample size is currently too small to analyze further, the PTAB’s two decisions eliciting varying market responses comport with our analysis on the impact of Bass’s IPRchallenges. The effect of the PTAB’s decision on patent holders’ stock returns becomes muted in its second decision denying Bass’s IPR challenge.

IV. Implications of the Empirical Findings for Public Policy

The findings of our event study invite further investigation. For example, although Bass’s initial challenges (that is, the first three challenges) resulted in a statistically significant decline in the share price of the holder of the challenged patents, the later challenges produced only one statistically significant negative effect. Four challenge events even yielded statistically significant positive returns of the patent holders. The results of this event study reveal that after the first few challenges, the effect of Bass’s IPR challenges became less predictable over time and were mostly insignificant both in statistical terms and in economic terms. The reduced effects of the IPR challenge indicate that a speculator expecting to profit from shorting a company’s stock before filing an IPR challenge and then closing the short position immediately thereafter could have profited by shorting the companies involved in only six of the last sixteen IPR filing events in our sample of twenty-one distinct IPR filing events by Bass. Only one of the sixteen latest events had statistically significant negative returns relative to the S&P 500. Nonetheless, the market response to future IPR challenges could vary as market expectations of the potential harm from Bass’s IPR challenges change, especially as the PTABbegins to issue decisions on these challenges.

The effect on the patent holder’s returns of the two initial PTAB decisions regarding Bass’s IPRchallenges reveals a pattern consistent with the effect of Bass’s IPR challenges themselves. The PTAB’s denial of Bass’s first challenge against Acorda’s patent on August 24, 2015, coincided with statistically significant positive abnormal returns (in the three-day window). But the PTAB’s denial of Bass’s challenge against one of Biogen’s patents on September 2, 2015, did not show a statistically significant change in returns.

Upon completion of the IPR of Bass’s challenges, one could reexamine the market predictions of similar IPR challenges and assess the accuracy of the capital market’s initial reaction. Such an assessment will be useful in determining whether the capital market’s increasingly muted response to IPR challenges observed in this study was because the most damaging and likely-to-be-successful challenges were launched first, or because the novelty of using the IPRprocess for challenges lessened over time. If Bass’s strategy to use the initial novelty of the IPR process became lackluster and hence led to the capital market’s muted response toward the later challenges, then the market’s reaction to Bass’s early filings (a statistically significant abnormal decrease in the share price of the holders of challenged patents) could indicate either a market overreaction or the cost of the market’s assessment of the uncertainty inherent in a new legal procedure for determining patent value. According to that explanation, Bass’s later challenges could not have produced the same response once the market had incorporated into the share prices of pharmaceutical companies the uncertainty that resulted from the use of the IPR process by parties other than alleged infringers of the patents whose validity was being challenged. With respect to the later challenges, the market could have responded to the potential litigation cost to the company and not to the cost of the increased uncertainty in asset valuation.

Conclusion

We have found empirical evidence that Kyle Bass’s petitions for inter partes review of various pharmaceutical patents between February and September of 2015 did not consistently produce statistically significant negative returns in the patent holders’ share prices. In fact, the IPR challenges filed on June 8, 2015, against Pozen’s patent and August 24, 2015, against Hoffmann-La Roche’s and Insys Pharma’s patents produced statistically significant positive returns (although those results could be a statistical outlier or a product of significant market volatility). That the news of an IPR challenge did not consistently significantly affect the patent-holding companies’ stock prices in many of the analyzed cases implies that using IPRchallenges to affect stock prices and profiting by shorting a stock of a company with a challenged patent would not be a profitable investment strategy. The muted response of stock prices indicates that the IPR challenges are not revealing new information that change market participants’ expectations. A possible explanation for our results is that the market has adjusted to the threat of IPR challenges, such that companies with patents are not punished for challenges brought against them.

We also found evidence that the news of the PTAB’s ruling on Bass’s IPR challenge on August 24, 2015, resulted in statistically significant positive returns for the patent-holding company (over the three-day window). Yet, the PTAB’s ruling on September 2, 2015, regarding Bass’s challenge against Biogen’s patent did not induce statistically significant returns. Although two PTAB decisions constitute too small a sample size to draw meaningful conclusions, we find a similar pattern of a statistically significant market reaction to the PTAB’s initial decision and a muted market reaction to its subsequent decision.

Whether the lack of market reaction to the news of IPR challenges against pharmaceutical companies or the news of the PTAB’s ruling on those IPR challenges will continue as the PTABrenders decisions on Bass’s subsequent challenges is uncertain, but the evidence from the first eight months is that these challenges do not provoke the predicted strong and consistent response in the capital market.

Appendix I: Summary Statistics on Challenged Patents and Corporate Owners

Table 1 below provides summary statistics of the size of companies and the field of the challenged patent.

Table I.1: Descriptive Statistics of the Companies That Own theChallenged Patents52

| Company Name | Market Capital-ization in 2015 ($ Millions) |

Annual Sales in 2014 ($ Millions) |

Challenged Patents (Patent Nos.) | Year Founded | Number of Employees | Patent Filing Date | Description of Patented Technology |

| Acorda Therapeutics* |

1,510 | 421 | 8,663,685 | 1995 | 489 | July 20, 2011 | Neurological disorders (MS) |

| Acorda Therapeutics* |

1,441 | 421 | 8,007,826 | 1995 | 489 | Dec. 13, 2004 | Neurological disorders (MS) |

| Shire/NPS. Pharma. | 44,110 | 6,220 | 7,056,886 | 1986 | 5016 | Dec. 29, 2000 | Increase stability of therapeutic peptides |

| Jazz Pharma. | 10,250 | 1,240 | 7,895,059 | 2003 | 870 | Feb. 11, 2010 | Drug distribution system |

| Pharmacyclics | 20,140 | 492 | 8,754,090 | 1991 | 607 | Dec. 29, 2011 | Cancer treatment with inhibitors |

| Biogen IDEC Int’l |

99,640 | 10,030 | 8,759,393 | 1978 | 7550 | Mar. 4, 2011 | Prep for Transplantation medicine |

| Celgene Corp. | 92,290 | 8,430 | 6,045,501 | 1986 | 6012 | Aug. 28, 1998 | Drug delivery without exposure to fetus |

| Celgene Corp. | 88,840 | 8,430 | 5,635,517 | 1986 | 6012 | June 3, 1997 | Chemical composition to reduce levels of tumor necrosis |

| Celgene Corp. | 92,290 | 8,430 | 6,315,720 | 1986 | 6012 | Oct. 23, 2000 | Drug delivery avoiding adverse side effects |

| Pozen Inc. | 216 | 29 | 6,926,907 | 1996 | 12 | May 31, 2002 | Agent that raises the pH of the gastrointestinal tract |

| Pozen Inc. | 291 | 29 | 8,858,996 | 1996 | 12 | April 2, 2014 | Agent that raises the pH of the gastrointestinal tract |

| Pozen Inc. | 340 | 29 | 8,852,636 | 1996 | 12 | Oct. 3, 2013 | Agent that raises the pH of the gastrointestinal tract |

| Shire, Inc. | 44,110 | 6,220 | 6,773,720 | 1986 | 5016 | June 8, 2000 | Controlled-release composition |

| Horizon Pharma. |

5,171 | 464 | 8,495,621 | 2005 | 692 | June 24, 2010 | Method for treating a patient at risk of NSAID-associated ulcer |

| Anacor Pharma., Inc. |

5,672 | 50 | 7,582,621 | 2002 | 100 | Feb. 16, 2006 | Compounds useful for treating fungal infections |

| Anacor Pharma., Inc. |

5,672 | 50 | 7,767,657 | 2002 | 100 | Aug. 16, 2006 | Compounds useful for treating fungal infections |

| Hoffmann-La Roche | 229,840 | 52,450 | 8,163,522 | 1896 | 88,509 | May 19, 1995 | Human TNFreceptor |

| Insys Pharma., Inc. |

2,239 | 273 | 8,835,460 | 1990 | 382 | May 15, 2013 | Sublingual fentanyl spray and methods of treating pain |

| Insys Pharma., Inc. |

2,239 | 273 | 8,486,972 | 1990 | 382 | Jan. 25, 2007 | Sublingual fentanyl spray |

| Insys Pharma., Inc. |

2,239 | 273 | 8,835,459 | 1990 | 382 | May 15, 2013 | Sublingual fentanyl spray |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

1,361 | 437 | 8,440,703 | 1995 | 489 | Nov. 18, 2011 | methods of using sustained release aminopyridine compositions |

| Acorda Therapeutics |

1,395 | 437 | 8,354,437 | 1995 | 489 | Apr. 8, 2005 | methods of using sustained release aminopyridine compositions |

- See Nathan Mayer Rothschild and ‘Waterloo’, Rothschild Archive, https://www.rothschildarchive.org/contact/faqs/nathan_mayer_rothschild_and_waterloo[https://perma.cc/PL66-QAV3]. ↩

- A recent example is William Ackman’s short position against Herbalife, which Richard White places in historical context. See Richard White, Plutocrat Manipulates Stock? OldNews!, Reuters (Mar. 11, 2014), http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2014/03/11/plutocrat-manipulates-stock-old-news [http://perma.cc/3YXU-NB2F]; Joseph de la Vega, Confusión de Confusiones 25–27 (Emily Atmetlla trans., Marketplace Books 1996). ↩

- See Joseph Walker & Rob Copeland, New Hedge Fund Strategy: Dispute the Patent, Shortthe Stock, Wall St. J. (Apr. 7, 2015, 7:24 PM), http://www.wsj.com/articles/hedge-fund-manager-kyle-bass-challenges-jazz-pharmaceuticals-patent-1428417408. ↩

- See Tom Engellenner, Bass Goes Fishing: Trouble Ahead for Pharma, or for Hedge-FundTrolls?, Forbes (July 15, 2015, 10:05 AM), www.forbes.com/sites/danielfisher/2015/07/15/bass-goes-fishing-trouble-ahead-for-pharma-or-for-hedge-fund-trolls. ↩

- See Andrew Ward, Kyle Bass Plans Legal Action on Pharma Patents, Fin. Times (Jan. 7, 2015, 7:44 PM), http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a2a706a0-969c-11e4-922f-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3hUceI91O [https://perma.cc/9WYS-64AF]. For Bass’s comments on the role of the inter partes review (IPR) process to promote discovery of weak patents, see The “Innovation Act”: Hearing on H.R. 9 Before the H.R. Before theComm. on the Judiciary, 114th Cong. (2015). ↩

- See Susan Decker, Drugmakers Strike Back: Bass Blasted Over Patent Challenge, BloombergBusiness (July 30, 2015, 12:15 PM), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2015-07-29/drugmakers-strike-back-kyle-bass-blasted-over-patent-challenges[http://perma.cc/GNH4-T3JS]. ↩

- Matthew Bultman, Celgene Wants Sanctions for “Abusive” AIA Review Petition, Law360 (July 29, 2015, 4:59 PM), http://www.law360.com/articles/684758/celgene-seeks-sanctions-for-abusive-aia-review-petition [https://perma.cc/XWZ7-DZFH]. ↩

- The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) requires that an IPR petition identify the “real party in interest”—that is, at a minimum, “the party or parties at whose behest the petition has been filed”—“to assist members of the [PTAB] in identifying potential conflicts, and to assure proper application of the statutory estoppel provisions.” Office Patent Trial Practice Guide, 77 Fed. Reg. 48759 (Aug. 14, 2012). ↩

- Kyle Bass is a “real party in interest” in each of the sixteen IPR challenges that we analyze in this article. See Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 8,858,996, at 1, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VII LLC v. Pozen Inc., IPR No. 2014-01344 (P.T.A.B. June 5, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 6,926,907, at 1, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VII LLC v. Pozen Inc. IPR No. 2015-01241 (P.T.A.B. May 21, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 5,635,517, at 7, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VI LLC v. Celgene Corp., IPR No. 2015-01169 (P.T.A.B. May 7, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 6,315,720, at 1, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VI LLCv. Celgene Corp., IPR No. 2015-01103 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 23, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 8,759,393, at 2, Coal. for Affordable Drugs V LLC v. Biogen IDEC Int’l GmbH, IPR No. 2015-01086 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 22, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 7,895,059, at 2, Coal. for Affordable Drugs III LLC v. Jazz Pharms., Inc., IPR No. 2015-01018 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 6, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 7,056,886, at 4, Coal. for Affordable Drugs II LLC v. NPS Pharms., Inc., IPR No. 2015-00990 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 1, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 6,773,720, at 1, Coal. for Affordable Drugs II LLC v. Shire Inc., IPR No. 2015-00988 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 1, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. No. 8,007,826, at 1, Coal. for Affordable Drugs (ADROCA) LLC v. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., IPR No. 2015-00817 (P.T.A.B. Feb. 27, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. No. 8,663,685, at 1, Coal. for Affordable Drugs (ADROCA) LLC v. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., IPR No. 2015-00720 (P.T.A.B. Feb. 10, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. No. 8,754,090, at 3, Coal. for Affordable Drugs IV LLC v. Pharmacyclics, Inc., IPR No. 2015-01076 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 20, 2015). ↩

- Biogen has argued that Hayman Capital Management LP’s offering documents submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission that state the objectives, risks, and terms of investment for the two funds that Hayman Capital filed in June 2015 would be useful in establishing Bass’s “ulterior purpose or motive” for filing the IPR petitions. See Kevin Penton, Biogen Wants Kyle Bass to Give Up Financial Docs at PTAB, Law360 (July 9, 2015), http://www.law360.com/ articles/677449/biogen-wants-kyle-bass-to-give-up-financial-docs-at-ptab [http://perma.cc/JV68-9L25]. ↩

- Petitioner’s Response in Opposition to Patent Owner Motion for Sanctions at 2, Coalition for Affordable Drugs VI LLC v. Celgene Corp., IPR No. 2015-01169 (P.T.A.B. May 7, 2015). ↩

- Id. at 1 (emphasis in original). ↩

- Id. at 2–3. ↩

- Id. at 3. ↩

- Id. at 6 (“The balance of Celgene’s ‘relevant facts’ primarily quotes various press reports and editorials speculating about or criticizing CFAD for filing Petitions to make a profit. These articles are not evidence or authority—and even if they were, they do not establish abuse of process. . . . Moreover, short selling is common, legal, and regulated.”) (citing Short Sales, Exchange Act Release No. 34-48709, 68 Fed. Reg. 62,972, 62974 (proposed Oct. 28, 2003)). ↩

- Id. at 14. ↩

- The PTAB denied the CFAD’s petition on the basis that the CFAD did not make the threshold showing that Acorda Therapeutics’s posters displaying the information of the to-be-patented drugs in question constituted prior art. Because the CFAD did not sufficiently establish “a reasonable likelihood that it would prevail with at least one of the claims challenged in the petition” as required under 35 U.S.C. § 314(a), the PTAB decided against instituting the IPR challenges against Acorda’s two patents. See Decision Denying Institution of Inter Partes Review at 2, Coalition for Affordable Drugs (ADROCA) LLC v. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., IPR No. 2015-00817 (P.T.A.B. Aug. 24, 2015).

↩ - On October 7, 2015 the PTAB instituted an IPR against two VirnetX patents. The board decided that a hedge fund called The Mangrove Partners Master Fund Ltd. has shown a “reasonable likelihood” that the patents are invalid after rejecting petitions by Apple Inc. and Microsoft. Ryan Davis, Hedge Fund Gets PTAB to Eye VirnetX Patents in Apple Case, Law 360 (Oct. 7, 2015), http://www.law360.com/ip/articles/712078. ↩

- Order at 3, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VI LLC v. Celgene Corp., IPR No. 2015-01092, IPRNo. 2015-01096, IPR No. 2015-01102, IPR No. 2015-01103, IPR No. 2015-01169 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 25, 2015). ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. ↩

- See Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Pub. L. No. 112–29, 125 Stat. 284 (2011). ↩

- See 35 U.S.C. § 311 (2012). ↩

- See id. § 311(b). ↩

- David Cavanaugh & Chip O’Neill, A Practical Guide to Inter Partes Review: StrategicConsiderations for Pursuing Inter Partes Review in a Litigation Context, WilmerHale (June 20, 2013), http://www.wilmerhale.com/uploadedfiles/wilmerhale_shared_content/wilmerhale_files/events/wilmerhale-webinar-ipr1-20jun13.pdf [http://perma.cc/7NQC-HJD6]. The initial filing fee for an interpartes review could be higher than the filing fee for an inter partes reexamination. SeeFive Things You Should Know About the Replacement of Inter Partes Reexamination withInter Partes Review on September 16, 2012, Hunton & Williams 2 (July 2012), https://www.hunton.com/files/News/154efdb7-f84c-4a59-aa63-88680b6228b7/Presentation/NewsAttachment/aaf2dbf6-9aa2-4553-bd3f-8900c93962be/IP_Alert_5_Things_You_Should_Know.pdf [https://perma.cc/EPU5-7KMA]. However, the shorter time to decision of inter partes review, relative to inter partesreexamination, could cause the cost of an inter partes review to be lower than that of an inter partes reexamination. See id. ↩

- Brian J. Love & Shawn Ambwani, Inter Partes Review: An Early Look at the Numbers, 81 U. Chi. L. Rev. Dialogue 93, 99 (2014), https://lawreview.uchicago.edu/sites/lawreview.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/Love_Ambwani_Dialogue.pdf. ↩

- Inter Parte Reexamination Filing Data, U.S. Patent & Trademark Off. 1 (Sept. 30, 2013), http://www.uspto.gov/patents/stats/inter_parte_historical_stats_roll_up_EOY2013.pdf; see also Love & Ambwani, supra note 26, at 95 n.9. ↩

- See, e.g., Leslie A. McDonell, Inter Partes Review: Tips for the Patent Holder, Law360 (May 24, 2013), http://www.finnegan.com/resources/articles/articlesdetail.aspx?news=339129db-4df9-4439-a216-91cca9ba55f3 [http://perma.cc/42SS-E2S6]. ↩

- See generally Love & Ambwani, supra note 26, at 94 (“Litigation proceeding in parallel with an instituted IPR is stayed about 82 percent of the time.”). ↩

- See Bruce Barker, The Benefits and Risks of Inter Partes Review: A Patent Challenger’s Perspective 1 (June 2013), http://www.chllp.com/downloads/ Benefits_Risks_IPR.pdf[http://perma.cc/PE7F-LK5Y]. ↩

- 35 U.S.C. § 314(a) (2012). ↩

- Daniel C. Mulveny, Post Grant Review, Inter Partes Review, and SupplementalReexamination Procedures, Am. Intell. Prop. L. Ass’n 13 (2012), http://www.aipla.org/committees/ committee_pages/IP-Practice-in-the-Far-East/trips/Documents/2012/Taiwan/ Dan%20Mulveny%20Presentation%20on%20PGR%20IPR%20Supp%20Reexam%20for%20Taiwan-Korea%20%28April%202012%29.pdf. ↩

- Patrick Driscoll & Michael McNamara, Inter Partes Review Initial Filings of ParamountImportance: What Is Clear After Two Years of Inter Partes Review Under the AIA, Mintz Levin (Oct. 21, 2014), http://www.mintz.com/newsletter/2014/Advisories/4363-1014-NAT-IP [http://perma.cc/GGF3-N84C]; see also Love & Ambwani, supra note 26, at 94. ↩

- See Barker, supra note 30, at 3. ↩

- 35 U.S.C. § 316(e) (2012). ↩

- Id. § 282(a). ↩

- Microsoft Corp. v. i4i Ltd. Partnership, 131 S. Ct. 2238, 2242 (2011). ↩

- See Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Pub. L. No.112-29, 125 Stat. 284, 300 (2011). ↩

- Love & Ambwani, supra note 26, at 97. ↩

- Driscoll & McNamara, supra note 33. ↩

- That reduction in costs should affect some challenges more than others. For example, the number of challenges against smaller companies should increase because of the reduction in the fixed costs of a challenge. The number of challenges against more diversified companies should also increase because the relative change in share price necessary for a challenge to be profitable has declined. ↩

- Jonah B. Gelbach, Eric Helland & Jonathan Klick, Valid Inference in Single Firm, Single-Event Studies, 15 Am. L. & Econ. Rev. 495 (2013), http://aler.oxfordjournals.org/ content/15/2/495.abstract ↩

- Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 8,858,996, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VII LLC v. Pozen Inc., IPR No. 2014-01344 (P.T.A.B. June 5, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 6,926,907, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VII LLC v. Pozen Inc., IPR No. 2015-01241 (P.T.A.B. May 21, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 5,635,517, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VI LLC v. Celgene Corp., IPR No. 2015-01169 (P.T.A.B. May 7, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 6,315,720, Coal. for Affordable Drugs VI LLC v. Celgene Corp., IPR No. 2015-01103 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 23, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 8,759,393, Coal. for Affordable Drugs V LLC v. Biogen IDEC Int’l GmbH, IPR No. 2015-01086 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 22, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 7,895,059, Coal. for Affordable Drugs III LLC v. Jazz Pharmas., Inc., IPR No. 2015-01018 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 6, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 7,056,886, Coalition for Affordable Drugs II LLC v. NPS Pharmas., Inc., IPR No. 2015-00990 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 1, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. Patent No. 6,773,720, Coal. for Affordable Drugs II LLC v. Shire. Inc., IPR No. 2015-00988 (P.T.A.B. Apr.1, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. No. 8,007,826, Coalition for Affordable Drugs (ADROCA) LLC v. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., IPR No. 2015-00817 (P.T.A.B. Feb. 27, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. No. 8,663,685, Coal. for Affordable Drugs (ADROCA) LLC v. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., IPR No. 2015-00720 (P.T.A.B. Feb. 10, 2015); Petition for Inter Partes Review of U.S. No. 8,754,090, Coal. for Affordable Drugs IV LLC v. Pharmacyclics, Inc., IPR No. 2015-01076 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 20, 2015). ↩

- See Aswarth Damodaran, Revenue Multiples by Sector (US), Damodaran Online, http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/psdata.html[http://perma.cc/VU2W-GFFA] (last updated Jan. 2015). ↩

- *Indicates that the date on which Bass filed the IPR challenge coincided with the date on which the press reported on that challenge. Shire, Inc., acquired NPS Pharmaceuticals on February 21, 2015, less than two months before the filing of Bass’s IPR petition against NPS Pharmaceuticals’ patent. The challenge on April 23, 2015, was filed against both Shire, Inc., and NPS Pharmaceuticals. We also exclude the multiple petitions that Bass filed against Celgene’s same patent on April 23, 2015, and the multiple petitions that Bass filed against Anacor’s same patent on August 20, 2015. The business press did not report on Bass’s third IPR challenge against Pozen’s, Horizon Pharmaceutical’s, or Bristol-Myers Squibb’s patent within the three-day window of the filing date. Bass also challenged two patents owned by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Because the University of Pennsylvania is not a publicly traded company and has no stock price information, we exclude challenges against its patents from our event study. A speculator is unable to short sell and profit from an organization’s stock that is nonexistent. ↩

- S&P 500, S&P Dow Jones Indices, https://us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-500[http://perma.cc/E655-Z9SK] (“The S&P 500 is widely regarded as the best single gauge of large-cap U.S. equities. . . . The index includes 500 leading companies and captures approximately 80% coverage of available market capitalization.”). ↩

- See The NYSE Arca Pharmaceutical Index (DRG), N.Y. Stock Exchange, https://www.nyse.com/publicdocs/nyse/indices/nyse_arca_pharmaceutical_index.pdf[http://perma.cc/D8E2-2WLA] (2014). ↩

- See Walker & Copeland, supra note 3. ↩

- Shire, Inc., acquired NPS Pharmaceuticals on February 21, 2015, less than two months before the filing of Bass’s IPR petition against NPS Pharmaceuticals’ patent. The challenge on April 23, 2015, was filed against both Shire, Inc., and NPS Pharmaceuticals. We further exclude the multiple petitions that Bass filed against Celgene’s same patent on April 23, 2015. Bass also challenged two patents owned by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Because the University of Pennsylvania is not a publicly traded company and has no stock price information, we exclude challenges against its patents in our event study. We also exclude the multiple petitions that Bass filed against Anacor’s same patent on August 20, 2015. In addition, Bass’s filing against Hoffmann-La Roche’s patent was made on Saturday, August 24, 2015. As U.S. stocks do not trade on Saturdays, we use the following Monday’s cumulative abnormal returns. ↩

- See Noel Randewich, Wall St. Posts Worst Day in Four Years, S&P 500 Now in Correction, Reuters (Aug. 24, 2015, 6:55 PM), http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/08/24/us-markets-stocks-usa-idUSKCN0QT10W20150824 [http://perma.cc/5R28-QC28]; Myles Udland, Stocks Get Clobbered in a Chaotic Day on Wall Street, Bus. Insider (Aug. 24, 2015, 4:00 PM), http://www.businessinsider.com/closing-bell-august-24-2015-8[http://perma.cc/A26V-LAVR]; Neil Irwin, Why the Stock Market Is So Turbulent, N.Y. Times (Aug. 24, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/25/upshot/why-global-financial-markets-are-going-crazy.html [http://perma.cc/V8S6-8LRC]. ↩

- Shire, Inc., acquired NPS Pharmaceuticals on February 21, 2015, less than two months before the filing of Bass’s IPR petition against NPS Pharmaceuticals’ patent. Consequently, we exclude NPS Pharmaceuticals from our analysis. We further exclude the multiple petitions that Bass filed against Celgene’s same patent on April 23, 2015. Bass also challenged two patents owned by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Because the University of Pennsylvania is not a publicly-traded company and has no stock price information, we exclude challenges against its patents in our event study. We also exclude the multiple petitions that Bass filed against Anacor’s same patent on August 20, 2015. In addition, Bass’s filing against Hoffmann-La Roche’s patent was made on Saturday, August 22, 2015. As U.S. stocks do not trade on Saturdays, we use the following Monday’s cumulative abnormal returns. ↩

- * Indicates petitions that Bass filed more than once for the same patent. Shire, Inc., acquired NPS Pharmaceuticals on February 21, 2015, less than two months before the filing of Bass’s IPR petition against NPS Pharmaceuticals’ patent. The challenge on April 23, 2015, was filed against both Shire, Inc., and NPS Pharmaceuticals. Bass also challenged two patents owned by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Because the University of Pennsylvania is not a publicly traded company, we exclude challenges against its patents in our event study. A speculator is unable to short sell and profit from an organization’s stock that is nonexistent. ↩