Abstract

This Essay puts forward a two-element argument that noncitizen defendants can use to establish that they have been interrogated for Miranda purposes when they have been questioned about their immigration status by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers. I examine the briefing and decision in one defendant’s case to illustrate why this two-element argument matters, and why it may be successful. The first element requires the defendant to show that ICE questioned her in a Federal District with a high rate of prosecution of immigration-related crimes. The second element requires the defendant to show that ICE sought to criminalize her for a reason in addition to civil deportation. If a defendant can show both elements, she can show she was interrogated for Miranda purposes. The overall argument comes from precedent cases from the Ninth Circuit, so for the first element, I focus on historical data on immigration-related prosecutions from the Southern District of California and the District of Arizona—two of the five Federal Districts which prosecute immigration offenses at the highest rate. I argue defendants can always satisfy the first element in these Districts. For the second element, I suggest a possible reason in addition to civil deportation on which defendants everywhere could rely. Based on ICE’s general self-portrayal and how ICE enforces immigration law nationally, I argue that ICE always has an interest in punishing unauthorized noncitizens for being unauthorized noncitizens, so all noncitizen defendants can satisfy the second element.

Introduction

Though most immigration law violations are enforced through civil proceedings,[1] the federal government has discretion to prosecute certain immigration-related offenses as crimes.[2] In 2019,[3] the federal government won conviction against 29,354 people for immigration-related crimes.[4] More people were convicted for immigration-related crimes in that year than for any other category of federal crime.[5] Generally, more than 99 percent of immigration-related convictions result from pleas.[6] Operation Streamline—the ongoing[7] policy of zero tolerance for unlawful entry offenses—facilitates this sky high plea rate.[8] Under Operation Streamline, (primarily Latinx) noncitizen defendants are prosecuted en masse in courtrooms dedicated to hearing unlawful entry cases only, and these defendants receive few procedural protections.[9] Given these circumstances, protecting noncitizen defendants’ constitutional rights in criminal proceedings is vital.

As a partial response, this Essay examines the case of Juan Manuel Valenzuela-Sanchez, a noncitizen whom an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent questioned about his immigration status.[10] Mr. Valenzuela argued at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals that the questioning violated his Fifth Amendment rights. Here, I consider whether the Court ruled correctly in Mr. Valenzuela’s case. In doing so, I argue that a noncitizen whom ICE questions about her immigration status within a Federal District in which immigration-related crimes are frequently prosecuted can always show she was interrogated for Miranda[11] purposes, so long as she can show that ICE had some reason to criminalize her, beyond simply securing her deportation. I then argue that ICE always has such an alternate reason to criminalize a noncitizen; ICE has an interest in punishing unauthorized noncitizens simply for being unauthorized noncitizens, and therefore ICE always has a reason beyond civil deportation to criminalize an unauthorized noncitizen.

My argument relies on a Ninth Circuit case which held that whether a noncitizen questioned about her immigration status was interrogated for Miranda purposes can depend on the rate of prosecution for immigration-related crimes in the Federal District in which the noncitizen was questioned.[12] Only courts in the Ninth Circuit must follow the rule from this case, so most of my analysis focuses on Mr. Valenzuela (whom ICE questioned in the Southern District of California)[13] and future defendants in the Southern District of California and the District of Arizona—the two Federal Districts in the Ninth Circuit with the highest rates of immigration-related prosecutions.[14] However, I ultimately frame my argument as generally applicable because noncitizens may find it still holds sway in other Circuits.

Part I of this Essay explains the state of law on immigration-related questioning and interrogation in the Ninth Circuit prior to Valenzuela-Sanchez and illuminates the proper relevant rule: a noncitizen can show she was interrogated by ICE if she can show that the questioning took place in a Federal District in which immigration-related crimes are frequently prosecuted and that the officer had a reason to criminalize her in addition to civil deportation. Part II elaborates on Valenzuela-Sanchez, examining Mr. Valenzuela’s arguments and how the Court’s decision misunderstood an important precedent case when it failed to note that the precedent case relied on the questioning officer’s reasons for questioning the defendant – not the fact that the defendant was then in custody for an immigration-related crime – in determining whether an interrogation occurred. Part III proposes how a future defendant in Mr. Valenzuela’s situation could explain the relevant rule and make a winning case: She could argue that she was questioned in a Federal District in which immigration-related crimes are frequently prosecuted and that the officer who questioned her sought to criminalize her in order to punish her simply for being unauthorized.

I. Discerning the Rule: From Mathis to Chen

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1966 decision in Miranda v. Arizona requires law enforcement officers to read people their Fifth Amendment rights before interrogating them if those people are in custody.[15] In 1980, the Court clarified that an interrogation for Miranda purposes occurs when an officer asks someone a question that is “reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response.”[16] And in 1968, in Mathis v. United States, the Court further clarified that Miranda applies in civil investigations in which civil law administrators question individuals—not only in criminal investigations carried out by criminal law enforcers.[17]

Mathis mattered for immigrants’ rights because federal immigration enforcement officers technically enforce civil law.[18] When Mathis clarified that Miranda applies when civil law enforcement officers question individuals, Mathis opened the door for people questioned about their immigration status by federal immigration enforcement officers—not only criminal law enforcement officers—to show they were interrogated for Miranda purposes. Mathis did not clarify exactly when a civil enforcement officer has interrogated someone for Miranda purposes—let alone whether an ICE officer always interrogates a noncitizen when the officer asks the noncitizen about her immigration status. However, Mathis and relevant cases which followed did lay out at least two alternate sets of minimum facts that a noncitizen can use to prove she was interrogated for Miranda purposes: The “Knowledge Approach,” where she can prove the officer who questioned her knew she was in custody on immigration-related charges, and the “Prosecutorial Rate Approach” (PRA), where she can prove the Federal District in which she was questioned had a high rate of prosecutions for immigration-related crimes, and the government sought to criminalize her for a reason in addition to civil deportation.

The Knowledge Approach comes from U.S. v. Gonzalez-Sandoval.[19] In that case, a Border Patrol officer failed to Mirandize the Defendant Arturo Gonzalez-Sandoval when the officer questioned Mr. Gonzalez-Sandoval about where he was born and whether he had legal status in the United States.[20] At the time, the officer knew Mr. Gonzalez-Sandoval was in jail on immigration-related criminal charges.[21] The United States later sought to rely on Mr. Gonzalez-Sandoval’s answer to convict him for reentering the country without permission under 8 U.S.C. § 1326, and Mr. Gonzalez-Sandoval asked the Court to exclude his answers on the grounds that the officer’s questioning constituted an impermissible interrogation.[22] The Court agreed. Specifically, the Court held that the questioning was an interrogation for Miranda purposes because the officer “had reason to suspect that Gonzalez-Sandoval was in this country [without authorization]”[23] because the officer knew Mr. Gonzalez was in jail on immigration-related criminal charges.[24]

The PRA comes from Mathis and United States v. Chen.[25] In Mathis, the Court held that whether a questioning constitutes interrogation can depend on how often the given kind of questioning results in a criminal prosecution.[26] Chen built on this reasoning. In Chen, an INS agent failed to Mirandize the Defendant, Lin Chen, when the agent asked Mr. Chen questions about how he arrived in the United States.[27] The investigation took place in the District of Guam, and Mr. Chen presented evidence showing that in the six years preceding the questioning, “the F[ederal] P[ublic ]D[efender]’s office [in Guam] ha[d] represented 48 persons accused of illegal entry.”[28] Mr. Chen also demonstrated that when the agent questioned him, the agent was trying to secure leverage against Mr. Chen which the agent hoped to use to procure Mr. Chen’s testimony against one of Mr. Chen’s associates.[29] Based on these facts, Mr. Chen argued that the agent had impermissibly interrogated him for Miranda purposes.[30]

The Court agreed, stating its holding unequivocally:

[T]he prosecutor’s willingness to pursue charges against Chen in order to procure Chen’s testimony against [Mr. Chen’s associate], and the fact that Chen was questioned in a district that has a practice of prosecuting § 1325 violations—rendered [the agent’s] questioning of Chen an “interrogation” for Miranda purposes.[31]

In fact, the Court specifically reiterated that these two factors were dispositive at the end of its opinion when it stated:

[The] questioning of Chen in the circumstances of this case constituted an “interrogation” because the government’s interest in Chen’s testimony and the U.S. Attorney’s practice of pursuing § 1325 prosecutions combined to create a heightened threat that the defendant might actually face a § 1325 prosecution.[32]

Thus, the Court in Chen built on the reasoning in Mathis to articulate the PRA. The Court held that the agent had interrogated Mr. Chen about his immigration status because Mr. Chen was questioned in a Federal District with a high rate of prosecutions for immigration-related crimes, and the agent sought to criminalize Mr. Chen for a reason in addition to civil deportation when he questioned Mr. Chen.

Two additional aspects of Chen are worth exploring. First, Mr. Chen was in the custody of the Immigration and Naturalization Service and thus in administrative holding—not police holding—when he was interrogated, according to the court.[33] This affirms the holding in Mathis that the criminal versus administrative distinction does influence whether questioning is an interrogation for Miranda purposes.[34] Second, though Mr. Chen was being held “because immigration officers believe that [he was] [] in the U.S. without authorization,”[35] the quotations included above demonstrate that the Court did not rely on the fact that the charges against Mr. Chen were immigration-related when it ruled that asking Mr. Chen about how he arrived in the United States constituted interrogation.[36] Therefore, the PRA is a completely separate approach from the Knowledge Approach for determining interrogation.

II. Valenzuela-Sanchez: The Facts, the Arguments,

and the Decision

This Part examines Valenzuela-Sanchez in which Mr. Valenzuela argued an ICE officer interrogated him for Miranda purposes, but the Ninth Circuit disagreed because the Court misunderstood the PRA from Chen. The facts of Valenzuela-Sanchez are as follows: In 2011, an investigator from ICE’s Criminal Alien Program asked Mr. Valenzuela questions about his citizenship while Mr. Valenzuela was in civil custody.[37] When Mr. Valenzuela was criminally charged in 2014 with reentering the United States without permission under 8 U.S.C. § 1326, the government sought to prove its case using Mr. Valenzuela’s statements from the 2011 questioning.[38] In turn, Mr. Valenzuela sought to have the statements suppressed.[39]

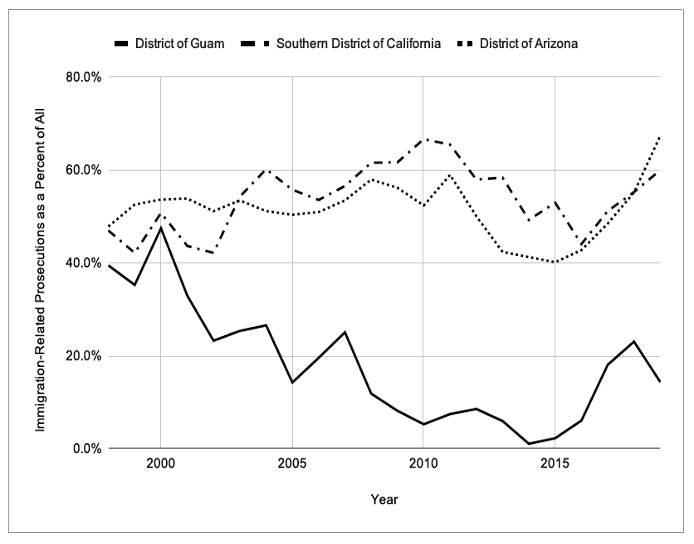

Mr. Valenzuela argued a variation of the PRA to show the officer had interrogated him. Mr. Valenzuela argued that Chen stood for the proposition that “questioning that would elicit [a noncitizen]’s admission of [unauthorized] presence in the United States will always constitute an ‘interrogation’ for Miranda purposes”—at least in the current era of federal prosecutions for immigration-related crimes.[40] To support this claim, Mr. Valenzuela cited Department of Justice statistics and a scholarly analysis of immigration-related prosecutions which showed that, nationally, federal prosecutions for immigration-related offenses rose “exponential[ly]”—from 2379 in 1983 to 34,894 in 2006 (when Chen was decided), and to 83,324 in 2011 (when Mr. Valenzuela was questioned).[41] The chart from Mr. Valenzuela’s brief in Figure 1[42] captured this reality well.

Figure 1: Annual Number of Federal Prosecutions for Immigration-Related Crimes From 1983 to 2011

Relying on data from TRAC Immigration,[43] Mr. Valenzuela also showed that an undocumented noncitizen interrogated in 2011 was “ten times more likely to be criminally prosecuted than a similarly-situated immigrant in 2006.”[44] Finally, comparing these figures to Chen, Mr. Valenzuela argued:

[I]f the defendant in Chen was at a “heightened risk” of prosecution where 48 defendants had been charged with illegal entry in the last six years (which comes out to about eight prosecutions a year), then it would be impossible to find that the unprecedented recent surge in immigration-related prosecutions does not answer the unresolved issue of “whether questioning that would elicit [a noncitizen]’s admission of [unauthorized] presence in the United States will always constitute an interrogation for Miranda purposes.”[45]

In essence, Mr. Valenzuela argued that, since the nationwide rate of prosecutions for immigration-related crimes in 2011 had increased significantly from when Chen was decided, any questioning about immigration status constituted an interrogation for Miranda purposes.

Mr. Valenzuela also argued that, in the alternative, the Court should find that the ICE officer had interrogated Mr. Valenzuela because his case so closely resembled—or was even more convincing than—cases in which the Court had found that an interrogation had occurred.[46] For example, Mr. Valenzuela argued that because he was questioned in the Southern District of California—a federal district whose immigration-related prosecutions in the year in which Mr. Valenzuela was questioned “dwarf[ed]” those the Chen Court found—he was at a heightened risk of self-incrimination and had therefore been interrogated.[47]

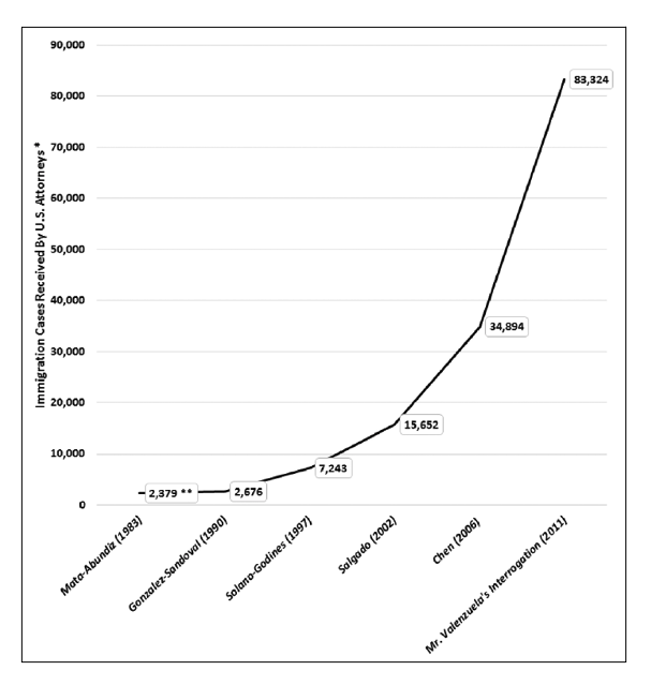

Had Mr. Valenzuela succeeded on his primary argument, the precedent set would have been far-reaching and relatively clear: So long as the national average rate of prosecutions for immigration-related crimes remained high compared to the rate of these prosecutions in the District of Guam when Chen was decided, an officer asking someone about her citizenship in the Ninth Circuit would always be interrogating that person. The most recent data available from the Department of Justice,[48] depicted in Figure 2, would seem to support that, though the number of prosecutions for immigration-related crimes has dropped from its all-time high, the number is still so much higher than it was in 2006, when Chen was decided, that Mr. Valenzuela’s proposed rule would still apply today.

Figure 2: Annual Number of Federal Prosecutions for Immigration-Related Crimes from 1998 to 2016

The adoption of Mr. Valenzuela’s rule would have been a milestone result with the potential to produce more fair outcomes than those that proceeded it.[49] All defendants whom the government sought to convict based on un-Mirandized questioning related to immigration status could have cited to Mr. Valenzuela’s case to argue this questioning constituted interrogation for Miranda purposes.

However, the Court disagreed with both Mr. Valenzuela’s arguments.[50] Regarding Mr. Valenzuela’s categorical argument, the Court stated Mr. Valenzuela “cite[d] no authority generally requiring [Miranda] warnings” for questioning related to immigration status, and the Court worried that “such a rule would assume that every person detained and questioned by an immigration agent intends to commit an immigration-related crime in the future . . . counter to the fact-specific inquiry required for determining whether a Miranda warning is necessary.”[51] The Court also rejected Mr. Valenzuela’s analogy of his specific circumstances to those in Chen.[52] The Court stated that Mr. Valenzuela was unlike Mr. Chen because Mr. Valenzuela was not “targeted in a criminal investigation of his entry into the United States” when he was questioned.[53] This statement was in error, however, because as discussed in Part I, the Chen Court ruled for Mr. Chen not because he was suspected of an immigration-related crime but because Mr. Chen’s questioning officer sought to criminalize him for a reason in addition to civil deportation—to pressure Mr. Chen to testify against his associate—and there was a high rate of prosecution for immigration-related crimes in the district in which Mr. Chen was questioned.[54]

This error by the Court underscores why proper explanation of the PRA from Chen is important: The way Mr. Valenzuela explained Chen was incomplete, and when the Court misconstrued the holding of Chen, it closed the door to relying on the PRA from Chen.

III. Moving Forward From Valenzuela-Sanchez: A Proposal

This Part proposes how a future defendant in Mr. Valenzuela’s situation could argue her case based on how the Court ruled in Valenzuela-Sanchez. She could argue she satisfies the first element of the PRA because the Southern District of California, the District in which Mr. Valenzuela was interrogated, frequently prosecutes immigration-related crimes. She could argue she satisfies the second element of the PRA because ICE seeks to punish unauthorized people simply for being unauthorized, so the ICE officer who questioned her had a reason in addition to civil deportation to criminalize her.

A. Element 1: High Rates of Immigration-Related Prosecutions

in the Southern District of California and the District of Arizona

First, while Mr. Valenzuela provided evidence of high national rates of prosecution for immigration-related offenses,[55] the PRA requires proof that the specific Federal District in which the defendant was questioned has a high rate of prosecution for immigration-related crimes. This Subpart shows that Mr. Valenzuela could have established this element of the PRA.

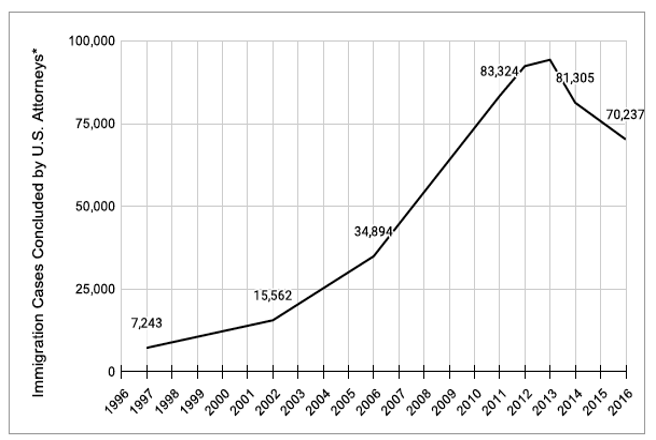

As Figures 3 and 4 below demonstrate,[56] the most recent available data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission shows that the District in which Mr. Valenzuela was questioned—the Southern District of California[57]—did have a high rate of prosecution for immigration-related crimes as defined by the Chen Court.[58] Far more immigration-related crimes were prosecuted in the Southern District of California in 2011 than the Chen Court found in the District of Guam: 3163 immigration-related crimes were prosecuted in the Southern District of California in 2011, while only forty-eight immigration-related crimes were prosecuted in the District of Guam between 1998 and 2004.[59] In addition, immigration-related prosecutions were much larger as a percentage of all prosecutions in the Southern District of California in 2011 (when Mr. Valenzuela was interrogated) than in the District of Guam in 2001 (when Mr. Chen was interrogated)[60]: 65.4 percent compared to 32.9 percent.

Figure 3: Annual Number of Prosecutions for Federal Immigration-Related Crimes

in the District of Guam, the Southern District of California, and the District of Arizona From 1998–2019

Figure 4: Annual Prosecutions for Immigration-Related Crimes in the District of Guam, the Southern District of California, and the District of Arizona as a Percent of all Federal Prosecutions in Those Districts From 1998–2019

In addition, Figures 3 and 4 show that the annual number of prosecutions for immigration-related crimes—and those prosecutions as a percentage of all prosecutions—in the Southern District of California and the District of Arizona remain high compared to the District of Guam in 2001. Accordingly, a future defendant in the Southern District of California or the District of Arizona could argue she conclusively establishes the first element of the PRA: a high rate of prosecution for immigration-related crimes in the federal district in which she was questioned.[61]

B. Element 2: Punishment as a Reason Beyond Civil Deportation

Second, Mr. Valenzuela failed to explain and establish the second element of the PRA: that the government sought to criminalize the defendant for a reason in addition to civil deportation. The Chen Court specifically stated that Mr. Chen met his burden “because of the government’s interest in procuring Chen’s testimony [in addition to] the U.S. Attorney’s practice of prosecuting § 1325 violations.”[62] Accordingly, a future defendant in Mr. Valenzuela’s situation should discuss what reasons in addition to obtaining the defendant’s civil deportation account for asking a noncitizen incriminating questions.

The remainder of this Essay proposes one such reason that any noncitizen defendant in Mr. Valenzuela’s position could provide: ICE has an interest in punishing noncitizens just for being unauthorized noncitizens, so being able to punish an unauthorized noncitizen solely for being unauthorized is always a reason beyond civil deportation for an ICE officer to criminalize a noncitizen. This reason is potentially one among many that a defendant could provide, and other reasons may better fit particular cases.

ICE purports to protect the United States from national security and public safety risks that flow from cross-border crime and unauthorized immigration.[63] It uses deportation to exclude “criminal [noncitizens]” from U.S. communities,[64] retain the integrity of the immigration system,[65] and shrink the number of noncitizen “absconders” in the United States.[66]

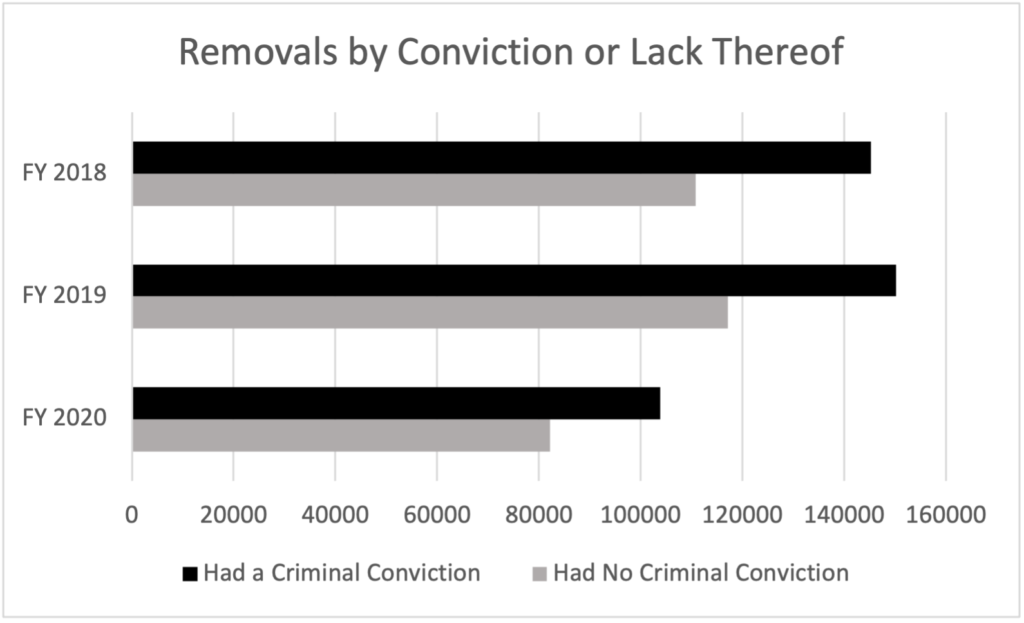

But reality does not bear out these reasons for deportation. First, as Figure 5 below shows, ICE deports tens of thousands of noncitizens every year who do not have a criminal conviction.[67] A desire to keep out criminal noncitizens cannot explain this fact. Second, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), the United States’ scheme governing all aspects of immigration and naturalization,[68] in no way suggests that the immigration system cannot be maintained unless its enforcers deport all unauthorized noncitizens—or even as many noncitizens as is physically possible. Subpart (a) of INA § 237 explicitly gives the Attorney General discretion—rather than a mandate—to deport noncitizens who are deportable.[69] Moreover, Congress does not provide DHS with sufficient funding to arrest or deport all unauthorized noncitizens, so Congress assumes DHS—and therefore ICE—will use discretion to decide which unauthorized noncitizens should be deported.[70]

Figure 5: Removals by Conviction or Lack Thereof

On its face and in the context of ICE’s mission, the assertion that deportation shrinks the number of noncitizen “absconders” seems to suggest that the fewer unauthorized people there are in the United States, the less threat there is to national security and public safety. But numerous scholars and studies have found that neither a smaller unauthorized population nor an increase in deportations correlates with an increase in public safety.[71] And the idea that shrinking the unauthorized population correlates with an increase in national security is hard to prove. “National security” is a contested and amorphous term.[72] Statutes which define national security do so broadly, without enumerating a closed list of conditions for or components of national security.[73] On their own or as a group, economic, political, and military stability may constitute national security, but there is no clear consensus on this issue.[74] As a result, the idea that ICE deports people to increase national security is specious on its face: How can ICE know what does or does not increase national security if no legal consensus on the term exists? Indeed, how can ICE know that deporting unauthorized people will increase national security? Moreover, if ICE considers national security to be threat from terrorism, the reality of ICE’s enforcement further confirms that national security concerns are not the clear target of ICE deportations. In practice, removal campaigns in the wake of September 11, 2001 “resulted in record levels of deportations, with almost all of the noncitizens having nothing whatsoever to do with terrorism.”[75]

Because this practical context does not bear out ICE’s stated reasons for deportation, looking closely at the language that ICE uses to describe its activities is a reasonable alternative to interpreting ICE purposes. ICE purports to use deportation to shrink the number of noncitizen “absconders.”[76] It would be odd if this statement simply meant that ICE seeks to reduce the number of noncitizens without authorization who evade and hide from the government to avoid penalties, as the term absconders would suggest.[77] There are simply easier, cheaper ways to reduce the number of these noncitizens who evade and hide from the government. The Center for American Progress estimates that it costs ICE $2071 per person to investigate and identity a noncitizen within the country whereas it costs an additional $7999 to deport that person.[78] In comparison, simply allowing unauthorized noncitizens to register as present in the United States would ensure they were no longer absconders and would logically cost much less than deporting individuals. Since USCIS currently funds itself almost entirely through fees it charges noncitizens for virtually every immigration-related filing or petition they make,[79] the government could potentially even make money off of registering unauthorized noncitizens.

So how should we understand what ICE is telling us? The terms with which ICE explains its mission make its purposes clear. ICE’s statement—which word-for-word says it uses deportation to “reduce the number of [noncitizen] absconders in the U.S.”[80]—means what it says. ICE seeks to reduce the number of noncitizens without authorization simply for being noncitizens without authorization. In other words, ICE sees removing unauthorized people—no matter who they are—as a good in and of itself. Or put yet another way, ICE ensures that deportation is the consequence of simply breaking immigration law for unauthorized people.

Just as federal immigration officers typically enforce civil law,[81] immigration violations are technically civil infractions. Although immigration-related criminal offenses exist, unauthorized presence is a civil rather than criminal violation and deportation proceedings are civil proceedings.[82] However, as the Supreme Court acknowledged in Padilla v. Kentucky, deportation does not resemble a civil penalty.[83] The results of deportation can be far worse than those of incarceration for a crime, let alone a civil monetary penalty. In the words of Justice Murphy, “[t]he impact of deportation upon the life of a [noncitizen] is often as great if not greater than the imposition of a criminal sentence. A deported [noncitizen] may lose his family, his friends and his livelihood forever. Return to his native land may result in poverty, persecution and even death.”[84] Deportation—the consequence the INA lays out for unlawful presence, among other things—is unnecessarily punitive; the consequence of violating this civil law goes far beyond the consequences of civil law in general.[85]

Acknowledging that deportation is a consequence that goes far beyond civil consequences ultimately demonstrates that ICE’s purpose in deportation is to punish unauthorized people just for being unauthorized. As discussed above, ICE penalizes unauthorized noncitizens solely for being unauthorized noncitizens. ICE penalizes these unauthorized noncitizens—again, solely for being unauthorized noncitizens—by subjecting them to penalties far harsher than they would face for a similar, non-authorization-related violation.[86] Since to punish someone is to treat someone in an unfairly harsh way,[87] and the treatment that unauthorized noncitizens face is disproportionate to penalties for other non-authorization-related violations, ICE uses deportation to punish unauthorized noncitizens for being unauthorized noncitizens.[88]

ICE thus has demonstrated that it punishes unauthorized noncitizens simply for being unauthorized. ICE officers therefore have a reason beyond civil deportation to seek out unauthorized noncitizens to ask them about their immigration status; by asking noncitizens about their immigration status, ICE can criminalize those noncitizens, further punishing them solely for being unauthorized noncitizens.[89]

Again, this reason beyond civil deportation which ICE has for criminalizing unauthorized noncitizens—punishing those unauthorized noncitizens simply for being unauthorized—is potentially one of many which a future plaintiff in Mr. Valenzuela’s situation could use to satisfy the second element of the PRA. And if she also can show she was questioned in a federal district in which immigration-related crimes are frequently prosecuted—element one—she can show she was interrogated for Miranda purposes.

Conclusion

Under Chen, defendants questioned by ICE about their immigration status can show they were interrogated if they were in a Federal District with a high rate of immigration-related prosecutions. This is because ICE always has a reason in addition to civil deportation to criminalize noncitizens; ICE is interested in punishing unauthorized noncitizens simply for being unauthorized noncitizens.

Though Chen may only be persuasive authority outside of the Ninth Circuit, the reasoning from this Essay can still point to the kinds of evidence which might be sufficient to show ICE desired to criminalize an unauthorized noncitizen for more than just civil deportation in any Circuit.[90] And if enough future cases relying on these reasons do succeed, the entire country can move closer to a truly categorical rule for interrogation as applied to questioning regarding immigration status.

[1]. Padilla v. Kentucky, 559 U.S. 356, 357–65 (2010) (“Although removal proceedings are civil in nature . . . deportation is nevertheless intimately related to the criminal process.

[2]. Immigration-related offenses are crimes for which the government must prove the defendant is a noncitizen in order to win conviction.

[3]. This Essay relies on data from 2019 because the federal government placed numerous new restrictions on border crossing beginning in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. See, e.g., Notification of Temporary Travel Restrictions Applicable to Land Ports of Entry and Ferries Service Between the United States and Mexico, 85 Fed. Reg. 16,547 (Mar. 24, 2020) (to be codified at 19 C.F.R. ch. 1); Notification of Temporary Travel Restrictions Applicable to Land Ports of Entry and Ferries Service Between the United States and Canada, 85 Fed. Reg. 16,548 (Mar. 24, 2020) (to be codified at 19 C.F.R. ch. 1).

[4]. U.S. Sentencing Comm’n, Overview of Federal Criminal Cases, Fiscal Year 2019, 5 (2020), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/research-and-publications/research-publications/2020/FY19_Overview_Federal_Criminal_Cases.pdf [https://perma.cc/B87H-MTFN].

[5]. Id. Immigration-related crimes made up 38.4 percent of all federal criminal convictions, whereas drug-related crimes, the category with the second-highest number of convictions, made up only 26.6 percent of all federal criminal convictions. Id.

[6]. “Statistical Information Packet Fiscal Year 2019 District of Arizona,” United States Sentencing Commission, at 3, available at: https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2019/az19.pdf [https://perma.cc/4QQM-KDKT];“Statistical Information Packet Fiscal Year 2019 Southern District of California,” United States Sentencing Commission, at 3, available at: https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2019/cas19.pdf.

[7]. Operation Streamline continues, despite the facts that it has been renamed the “Criminal Consequence Initiative” and that the federal government has summarily expelled—rather than criminally prosecuted—most individuals who have tried to enter the United States without authorization during the COVID-19 pandemic under Title 42, a provision which allows the Department of Health and Human Services to suspend immigration entries in a health crisis. Comm. on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Combined Tenth to Twelfth Reports Submitted by the United States of America Under Article 9 of the Convention, due in 2017, ¶ 87, U.N. Doc. CERD/C/USA/10-12 (June 8, 2021) ("Regarding Operation Streamline, now called the Criminal Consequence Initiative (CCI), as of February 2021, only the Del Rio sector uses CCI and uses it only sparingly."); 42 U.S.C. § 265 (“Suspension of entries and imports from designated places to prevent spread of communicable diseases”); Notification of Temporary Travel Restrictions Applicable to Land Ports of Entry and Ferries Service Between the United States and Mexico, 85 Fed. Reg. 16,547 (Mar. 24, 2020) (to be codified at 19 C.F.R. ch. 1); Notification of Temporary Travel Restrictions Applicable to Land Ports of Entry and Ferries Service Between the United States and Canada, 85 Fed. Reg. 16,548 (Mar. 24, 2020) (to be codified at 19 C.F.R. ch. 1). See also Press Release, U.S. Attorney’s Office, District of Arizona, United States Attorney's Office District of Arizona April 2021 Immigration and Border Crimes Report (May 25, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/usao-az/pr/united-states-attorneys-office-district-arizona-april-2021-immigration-and-border-crimes (“The Department of Homeland Security instituted a policy in March 2020 of expeditiously returning aliens who illegally enter the United States rather than detaining them. The decreased number of individuals presented to this Office for prosecution coincides with the implementation of that policy and other COVID-19 related border restrictions.”).

[8]. See Ingrid V. Eagly, The Movement to Decriminalize Border Crossing, 61 B.C.L. Rev. 1967, 1982–85 (2020).

[9]. Id. at 2004–05.

[10]. United States v. Valenzuela-Sanchez, 669 F. App’x 419 (9th Cir. 2016) (mem.); Appellant’s Opening Brief at 11, Valenzuela-Sanchez v. United. States, 669 F. App’x 419 (9th Cir. 2016) (mem.) (No. 15-50136) [hereinafter “Valenzuela’s Opening Brief”].

[11]. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). Miranda requires that questioning be both “custodial” and “interrogation” for an officer to be required to advise the questionee of her Fifth Amendment rights, but this Essay does not analyze the “custodial” requirement. Id. at 444.

[12]. See infra Part I.

[13]. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10 at 26.

[14]. The Southern District of California and the District of Arizona consistently rank among the top five federal judicial districts with the highest number of prosecutions for immigration-related charges. See Immigration Prosecutions for December 2020, TRAC Immigration (Jan. 20, 2021), https://trac.syr.edu/tracreports/bulletins/immigration/monthlydec20/fil [https://perma.cc/TZU7-YYTD]. In 2019, federal prosecutors pursued immigration-related charges against at least 3775 people in the District of Arizona and 2451 people in the Southern District of California. “Statistical Information Packet Fiscal Year 2019 District of Arizona,” supra note 6; “Statistical Information Packet Fiscal Year 2019 Southern District of California,” supra note 6. Location can partially account for these statistics; both districts are on the United States-Mexico border—the U.S. border which people cross most frequently—and together the districts are home to five of the ten busiest ports of entry in the country. See Geographic Boundaries of the United States Courts of Appeal and United States District Courts, U.S. Cts., available at: https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/federal-courts-public/court-website-links [https://perma.cc/CY59-NCPS] (last visited June 14, 2021); Border Crossing Entry Data 2019 Ranking, U.S. Dep’t of Transp., available at: https://explore.dot.gov/#/views/BorderCrossingData/CrossingRank (last visited June 14, 2021). However, both districts have also intentionally maximized enforcement of immigration-related crimes. Kristina Davis, San Diego Soon to Fast-Track Illegal Border Crossing Cases, San Diego Union-Trib. (June 29, 2018, 6:10 PM), https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/courts/sd-me-immigration-caseload-20180629-story.html [https://perma.cc/C7CM-W8S5] (quoting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of California Kelly Thornton announcing accelerated prosecution of unlawful entry cases); Ingrid V. Eagly, Local Immigration Prosecution: A Study of Arizona Before SB 1070, 58 UCLA L. Rev. 1749 (2011) (discussing implementation of a 2005 Arizona smuggling law created to criminalize noncitizens crossing the border into Arizona); Conor Friedersdorf, The Best Case Against Arizona’s Immigration Law: The Experience of Greater Phoenix, Atlantic (May 18, 2010) https://www.theatlantic.com/projects/the-future-of-the-city/archive/2010/05/the-best-case-against-arizonas-immigration-law-the-experience-of-greater-phoenix/56859/ [https://perma.cc/CZ22-AEWS].

[15]. Miranda, 384 U.S. at 444.

[16]. See Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291, 301 (1980); United States v. Booth, 669 F.2d 1231, 1237 (9th Cir. 1982).

[17]. See Mathis v. United States, 391 U.S. 1 (1968).

[18]. See, e.g., United States v. Salgado, 292 F.3d 1169, 1173 (9th Cir. 2002). Federal immigration enforcement officers are agents from ICE, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and, previously, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). See Homeland Security Act of 2002, 6 U.S.C. § 251 (transferring all functions of the INS to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)). ICE and CBP are agencies within DHS. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., Organizational Chart (Apr. 2, 2021) https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/21_0402_dhs-organizational-chart.pdf [https://perma.cc/9AN2-BK5H].

[19]. 894 F.2d 1043 (9th Cir. 1990).

[20]. Id. at 1046.

[21]. Id.

[22]. Id.

[23]. Id. at 1045, 1047.

[24]. See id. at 1046. This Essay does not discuss the Knowledge Approach further because it does not apply to Mr. Valenzuela’s case. The Valenzuela-Sanchez Court correctly noted that “At the time [of the questioning], he was neither targeted in a criminal investigation of his entry into the United States nor charged with an immigration-related crime,” so Mr. Valenzuela would have been unable to establish the Knowledge Approach. United States v. Valenzuela-Sanchez, 669 F. App’x 419, 419 (9th Cir. 2016) (mem.).

[25]. 439 F.3d 1037 (9th Cir. 2006).

[26]. Mathis v. United States, 391 U.S. 1, 4 (1968) (holding that a tax investigator who questioned Mr. Mathis as part of a routine administration tax investigation had interrogated Mr. Mathis in part because tax investigations frequently lead to criminal prosecutions).

[27]. Chen, 439 F.3d at 1038–39.

[28]. Id.

[29]. Id. at 1042.

[30]. Id.

[31]. Id.

[32]. Id. at 1043.

[33]. See id. at 1038.

[34]. See supra text accompanying notes 17.

[35]. Chen, 439 F.3d at 1038.

[36]. See infra text accompanying notes 32–33.

[37]. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 5–6; Answering Brief for the United States at 4–5, United States v. Valenzuela-Sanchez, 669 F. App’x 419 (9th Cir. 2016) (mem.) (No. 15-50136) [hereinafter Government’s Answering Brief].

[38]. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 5; Government’s Answering Brief, supra note 38, at 8.

[39]. See Valenzuela-Sanchez, 669 F. App’x at 419–20.

[40]. See Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 25 (emphasis added).

[41]. Id. at 23–24 (citing Mark Motivans, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Federal Justice Statistics, 2011–2012, at 12 (2015), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/fjs1112.pdf [https://perma.cc/WXV3-J6NR]; Mark Motivans, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Federal Justice Statistics, 2006 (2009), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/html/fjsst/2006/fjs06st.pdf [https://perma.cc/S2FX-3TSD]; Steven K. Smith & Mark Motivans, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Compendium of Federal Justice Statistics, 2002, at 9 (2004), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/cfjs02.pdf [https://perma.cc/47E2-G8W7]; Steven K. Smith & John Scalia, Jr., U.S. Dep’t of Just., Compendium of Federal Justice Statistics, 1997, at 16 (1999), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/cfjs97.pdf [https://perma.cc/DC4K-EPQQ]; Steven K. Smith & John Scalia, Jr., U.S. Dep’t of Just., Compendium of Federal Justice Statistics, 1990, at 12 (1993), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/cfjs90.pdf [https://perma.cc/3WNV-5PVG]; Thomas Hester & Carol G. Kaplan, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Federal Criminal Cases, 1980–87, at 7 (1989), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/fcc8087.pdf [https://perma.cc/WF4Z-9DJ6]; Anjana Malhotra, The Immigrant and Miranda, 66 SMU L. Rev. 277, 324 (2013)).

[42]. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 24. Mr. Valenzuela accredited the increase in part to Operation Streamline which Mr. Valenzuela described as a Department of Homeland Security program “intended to deter the [unauthorized] entry of people, weapons, and drugs into the country by vastly increasing the prosecution of persons entering the country without authorization” by “attempt[ing] to file criminal charges against virtually all persons apprehended for entering the country without authorization.” Id. at 22–23 (citing In re Approval of Jud. Emergency Declared in Dist. of Ariz., 639 F.3d 970, 980 (9th Cir. 2011)).

[43]. Decline in Federal Criminal Immigration Prosecutions, TRAC Immigration (June 12, 2012), https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/283 [https://perma.cc/9ZJ9-ZF6F].

[44]. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 23.

[45]. Id. at 25 (citing United States v. Chen, 439 F.3d 1037, 1043).

[46]. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 5.

[47]. Id. at 28–29.

[48]. Mark Motivans, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Federal Justice Statistics, 2015–2016, at 7 (2019), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/fjs1516.pdf [https://perma.cc/BSQ6-5VF2]; Mark Motivans, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Federal Justice Statistics, 2014, at 11 (2017), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/fjs14st.pdf [https://perma.cc/FY78-DEVR]; Mark Motivans, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Federal Justice Statistics, 2013–2014, at 17 (2017), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/fjs1314.pdf [https://perma.cc/B2R3-8L8H]; Mark Motivans, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Federal Justice Statistics, 2013, at 11 (2017), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/fjs13st.pdf [https://perma.cc/LE5T-U99D]; see sources discussing 1997, 2002, 2006, and 2011–12 federal justice statistics supra note 42.

[49]. See, e.g., Yolanda Vázquez, Constructing Crimmigration: Latino Subordination in a “Post-Racial” World, 76 Ohio State 599, 654 (2015) (discussing how prosecution for immigration-related offenses overwhelming criminalizes Latinx people).

[50]. United States v. Valenzuela-Sanchez, 669 F. App’x 419, 419–20 (9th Cir. 2016) (mem.).

[51]. Id. at 419.

[52]. Id.

[53]. Id.

[54]. See supra Part I (discussing United States v. Chen, 439 F.3d 1037, 1039 (9th Cir. 2006)).

[55]. See supra text accompanying notes 47–51 and Figure 2.

[56]. Figures 3 and 4 were created using data contained in the United States Sentencing Commission’s Statistical Information Packets. Statistical Information Packets, Fiscal Years 1998–2019, for the District of Arizona, the District of Guam, and the Southern District of California, U.S. Sentencing Comm’n, https://www.ussc.gov/research/data-reports/geography [https://perma.cc/SZY3-ZMA8].

[57]. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 28–29.

[58]. Chen, 439 F.3d at 1042–43 (finding the fact that Guam’s Federal Public Defender had represented 48 people accused of illegal entry between 1998 and 2004 supported the argument that the officer had interrogated Mr. Chen for Miranda purposes).

[59]. Id. at 1042. In fact, the U.S. Sentencing Commission data shows there were just four immigration-crimes prosecuted in the District of Guam in 2011. “Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2011, for the District of Guam,” U.S Sentencing Comm’n, https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2011/gu11.pdf [https://perma.cc/5BUQ-HGGL].

[60]. Chen, 439 F.3d at 1038–39.

[61]. Notably, Mr. Valenzuela did compare the prosecution rate of immigration-related crimes in the Southern District of California to that in Chen, and he used the comparison to argue the risk of prosecution was particularly high in his case. Valenzuela’s Opening Brief, supra note 10, at 26–29. He did not articulate the complete Prosecutorial Rate Approach (PRA) from Chen¸ however, nor did he use this evidence to satisfy the first prong of the PRA; instead, he mentioned it alongside evidence of the knowledge of criminal law the officer who questioned him had, analogizing to Mata-Abundiz. Id. As discussed in Part I, the Mata-Abundiz Court relied on additional evidence which was not available to Mr. Valenzuela (including the fact that the questioning officer knew Mr. Mata had been charged with immigration-related crimes), so the Court rejected Mr. Valenzuela’s analogy to Mata-Abundiz. See United States v. Valenzuela-Sanchez, 669 F. App’x 419, 419–20 (9th Cir. 2016) (mem.).

[62]. Chen, 439 F.3d at 1042.

[63]. See, e.g., U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t, https://www.ice.gov [https://perma.cc/382J-9PEH]. See also U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Resource Management and Operational Priorities: Hearing Before the Subcomm. On Homeland Sec. of the H. Comm. On Appropriations, 117th Cong. 2 (2021) (statement of Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AP/AP15/20210513/112599/HHRG-117-AP15-Wstate-JohnsonT-20210513.pdf [https://perma.cc/PQ64-RLHT] (“[ICE’s] deportation officers fulfill [Enforcement and Removal Operations’] important public safety and national security mission by identifying, arresting, or detaining removable noncitizens, and as required, removing noncitizens with final orders of removal.”); A Review of the Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Requests for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: Hearing Before the Subcomm. On Border Sec., Facilitation & Operations of the H. Comm. On Homeland Sec., 116th Cong. 21 (2019) (statement of Matthew T. Albence, Acting Director, U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-116hhrg37865/wp-content/uploads/securepdfs/2025/11/CHRG-116hhrg37865.pdf [https://perma.cc/738Y-7PWF ](“Looking ahead, the men and women of ICE will continue to do their sworn duty to enforce all laws with which we are charged . . . arresting, detaining, and removing . . . public safety threats, known or suspected terrorists, and immigration violators, all of which are critical to the National security, border security, and safety and well-being of our country.”).

[64]. See, e.g., Henry Lucero, EAD Message, U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t (Mar. 1, 2021), https://www.ice.gov/features/ERO-2020 [https://perma.cc/PW6E-6LXT]. See also Immigration and Customs Enforcement Budget Request for FY2021: Before the Subcomm. of Homeland Sec. of the H. Comm. on Appropriations, 116th Cong. 10–11 (2020) (statement of Matthew T. Albence, Acting Director, U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AP/AP15/20200311/110701/HHRG-116-AP15-Wstate-AlbenceM-20200311.pdf (“[D]etaining and removing illegal aliens, especially those criminals and public safety threats . . . constitutes an operational success that continues to yield important results for the safety of the nation.”).

[65]. See Lucero, supra note 67.

[66]. See, e.g., Removal, U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t (Jan. 7, 2021), https://www.ice.gov/remove/removal [https://perma.cc/8W4P-67XV]. See also Department of Homeland Security Appropriations for 2015: Hearings Before the Subcomm. of Homeland Sec. of the H. Comm. on Appropriations, 113th Cong. 10 (2015) (“[ICE’s] Enforcement and Removal Operations . . . locates and apprehends fugitive [noncitizens] in the United States. ICE strives to identify and apprehend all fugitives, with an emphasis on those [noncitizens] posing the greatest risk to public safety. This creates a deterrent to potential absconders and promotes the integrity of the immigration process.”).

[67]. U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t, Fiscal Year 2020 Enforcement and Removal Operations Report 23 (2020), https://www.ice.gov/doclib/news/library/reports/annual-report/eroReportFY2020.pdf [https://perma.cc/83WA-WC38].

[68]. See, e.g., De Canas v. Bica, 424 U.S. 351, 353 (1976) (describing the INA as “the comprehensive federal statutory scheme for regulation of immigration and naturalization.”).

[69]. Immigration and Nationality Act § 237(a), 8 U.S.C § 1227 (2019) ("Any [noncitizen] . . . in and admitted to the United States shall, upon the order of the Attorney General, be removed if the [noncitizen] is within one or more of the following classes of deportable [noncitizens]. . . .") (emphasis added).

[70]. See Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia, Americans in Waiting: Finding Solutions for Long Term Residents, 46 J. Legis. 29, 34–36 (2019) (“The use of prosecutorial discretion is inevitable. According to one guideline from 2011, the government only has the resources to remove about 400,000, or less than four percent, of the roughly 11.2 million people living in the United States without documentation.”); Hiroshi Motomura, Immigration Outside the Law 28 (2006) (“[T]he federal government tries to remove only a small fraction of the unauthorized migrants in the United States.”).

[71]. See Jennifer M. Chacón, Commentary, Unsecured Borders: Immigration Restrictions, Crime Control and National Security, 39 Conn. L. Rev. 1827, 1879–88 (2007); see also Michael T. Light & Isabel Anadon, Immigration and Violent Crime: Triangulating Findings Across Diverse Studies, 103 Marq. L. Rev. 939, 948–49, 953 (2020) (first citing, inter alia, David Green, The Trump Hypothesis: Testing Immigrant Populations as a Determinant of Violent and Drug-Related Crime in the United States, 97 Soc. Sci. Q. 506, 521 (2016) (finding undocumented immigration is generally not associated with violent crime); then citing Michael T. Light & Ty Miller, Does Undocumented Immigration Increase Violent Crime?, 56 Criminology 370, 370 (2018) (finding that undocumented immigration does not increase violence); then citing Christian Gunadi, On the Association Between Undocumented Immigration and Crime in the United States, 73 Oxford Econ. Papers, 200, 220 (2019) (“[T]he overall evidence from the analysis shows a weak link between undocumented immigration and violent crimes.”); then citing Thomas J. Miles & Adam B. Cox, Does Immigration Enforcement Reduce Crime? Evidence from Secure Communities, 57 J.L. & Econ. 937, 970–71 (2014) (finding an increase in deportations had no observable effect on violent crime); and then citing Elina Treyger, Aaron Chalfin & Charles Loeffler, Immigration Enforcement, Policing, and Crime: Evidence from the Secure Communities Program, 13 Criminology & Pub. Pol’y 285, 311 (2014) (finding that increasing deportations within the communities studied “has had no unambiguous beneficial effects”)); Annie Laurie Hines & Giovanni Peri, Immigrants’ Deportations, Local Crime and Police Effectiveness, IZA Inst. of Lab. Econs. (Discussion Paper Series), June 2019, at 1, 1 (finding “increases in deportation rates did not reduce crime rates for violent offenses or property offenses . . . . [Nor did they] increase[] either police effectiveness in solving crimes or local police resources.”).

[72]. N.Y. Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713, 719 (1971) (Black, J., concurring) (“The word ‘security’ is a broad, vague generality . . . .”); see also Laura K. Donohue, The Limits of National Security, 48 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1573, 1574–77 (2011) (surveying judicial and scholarly interpretations of the term and discussing their significant differences).

[73]. See, e.g., Classified Information Procedures Act, 18 U.S.C. app. § 1(b) (stating national security involves matters related to the “national defense and foreign relations of the United States”); 50 U.S.C. § 3003(5)(B)(iii) (2019) (stating intelligence related to “national security” refers to, among other things, “any [] matter bearing on United States national or homeland security”).

[74]. See Donohue, supra note 72, at 1584.

[75]. Kevin R. Johnson, Protecting National Security Through More Liberal Admission of Immigrants, 2007 U. Chi. Legal F. 157, 173 (2007).

[76]. See U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t, supra note 68.

[77]. See Abscond, Oxford Dictionary of English, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/abscond?q=abscond [https://perma.cc/653Y-L8R7].

[78]. See Philip E. Wolgin, What Would It Cost to Deport All 5 Million Beneficiaries of Executive Action on Immigration?, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Feb. 23, 2015, 8:53 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2015/02/23/106983/what-would-it-cost-to-deport-all-5-million-beneficiaries-of-executive-action-on-immigration [https://perma.cc/K9HL-9UY9]. The $7999 figure accounts for the costs of detaining, prosecuting, and ultimately returning a noncitizen to her country of origin. Id.

[79]. See, e.g., William A. Kandel, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R44038, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Functions and Funding 5–9 (2005).

[80]. See U.S. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t, supra note 67.

[81]. See discussion supra Introduction.

[82]. See, e.g., Padilla v. Kentucky, 559 U.S. 356, 357–65 (2010).

[83]. Id. at 365 (“We have long recognized that deportation is a particularly severe ‘penalty’ . . . . [D]eportation is . . . intimately related to the criminal process.”).

[84]. Bridges v. Wixon, 326 U.S. 135, 164 (1945) (Murphy, J., concurring); see also Padilla, 559 U.S. at 368 (internal quotation marks omitted) (“[P]reserving the [criminal defendant] client’s right to remain in the United States may be more important to the client than any potential jail sentence.”); Ng Fung Ho v. White, 259 U.S. 276, 284 (1922) (“[Deportation] obviously deprives [a person] of liberty . . . . It may result also in loss of both property and life; or of all that makes life worth living.”).

[85]. Civil Penalties, Legal Info. Instit. Cornell (accessed June 16, 2021),

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/civil_penalties_(civil_fines) (“Civil penalties usually only include civil fines or other financial payments as a remedy for damages [rather than incarceration.]”).

[86]. For example, taxation is an “indispensable ingredient in every constitution . . . a

deficiency [of which] subject[s] . . . the people . . . to continual plunder . . or sink[s] . . . the government . . . into a fatal atrophy.” The Federalist No. 30 (Alexander Hamilton). Yet the penalty for the civil offense of failing to file a federal income tax return is just 5 percent of the amount of tax required to be shown on the return for each month (or fraction thereof) that the return is late, but not exceeding 25 percent in the aggregate of the tax due. 26 U.S.C. § 6651(a)(1). The federal government also discounts this penalty if the person who failed to file agrees to an installment payment with the Internal Revenue Service. 26 U.S.C. § 6651(h). In comparison, deportation wholly removes someone from their community and way of life. See Bridges, 326 U.S. at 164 (Murphy, J., concurring).

[87]. Punish, Oxford Dictionary of English, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/punish [https://perma.cc/3QLS-ZVK8].

[88]. This Essay is far from the first to articulate that immigration enforcers—or the government in general—use deportation and other civil consequences to punish unauthorized noncitizens just for being noncitizens. See, e.g., Gabriel J. Chin, Illegal Entry as Crime, Deportation as Punishment: Immigration Status and the Criminal Process, 58 UCLA L. Rev. 1417, 1452–59 (2011) (arguing deportation is “quasi-punishment”); César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, Immigration Detention as Punishment, 61 UCLA L. Rev. 1346, 1346 (2014) (arguing that “the current immigration detention regime should be conceptualized as punishment”). The inevitable and worthy question then is: Why does ICE punish unauthorized noncitizens for being unauthorized noncitizens? Crimmigration scholarship—which explores both the criminalization of immigration law and the ways in which criminal law and immigration law have merged substantively and procedurally, effectively creating one unified system—provides potential answers to this question. See Vázquez, supra note 48, at 607 (introducing key scholars and scholarship on crimmigration). Such answers include maintaining white supremacy and driving profit through expanding the carceral state. For scholarship elaborating on the maintenance of white supremacy see, for example, id. at 618–19 (citing Gabriel J. Chin, Segregation’s Last Stronghold: Race Discrimination and the Constitutional Law of Immigration, 46 UCLA L. Rev. 1 (1998)). See also Jennifer M. Chacón, Loving Across Borders: Immigration Law and the Limits of Loving, 2007 Wis. L. Rev. 345, 349–55 (2007) (discussing immigration law from the Chinese Exclusion Acts through the Johnson-Reed Act which “distinguished [for admission purposes] persons of the ‘colored races’ from ‘white’ persons from ‘white’ countries” (quoting Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America 27 (2004))). See generally Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (rev. ed. 2012) (tracking how the criminal legal system was created to subordinate Black people through race-neutral laws); Kelly Lytle Hernández, City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, 1771–1965, at 137–39 (2017). For scholarship on how punishment of unauthorized noncitizens drives profit through the carceral state, see, for example, Elizabeth Jones, The Profitability of Racism: Discriminatory Design in the Carceral State, 57 U. Louisville L. Rev. 61, 78–83, 85 (2018) (”Following the election of Donald Trump, the increased crackdown against people who possibly crossed the border illegally has increased the stock value of private prison corporations.”).

[89]. This analysis requires accepting that the purposes and intents of an organization may be attributed to a specific agent working within that organization. This premise is undoubtedly contested. See, e.g., Nirej Sekhon, Purpose, Policing, and the Fourth Amendment, 107 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 65, 98–101 (2017) (discussing the confusing relationship between state purpose and officer purpose in criminal procedure cases). However, if this premise is rejected, noting that ICE as an organization is interested in punishing unauthorized noncitizens simply for being unauthorized can suggest the kind of specific evidence a defendant in a situation like Mr. Valenzuela’s could present to demonstrate that a questioning officer had reasons beyond civil deportation to criminalize her.

[90]. This evidence might include comments by ICE employees which suggest they are biased against unauthorized noncitizens in the United States simply because of those noncitizens’ unauthorized status. See, e.g., Roque Planas, Trump Hired a Cop to Run ICE. It Didn’t Work Out., HuffPost (Apr. 13, 2018, 12:40 PM), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/thomas-homan-trump-ice-director_n_5acbae94e4b09d0a11964dc4 [https://perma.cc/6J2V-RAPH] (quoting former ICE acting director Thomas Homan as saying, “[i]f you’re in this country illegally and you committed a crime by entering this country, you should be uncomfortable . . . . You should look over your shoulder, and you need to be worried.”).