Introduction

On Friday, April 11, and Saturday, April 12, 2014, the UCLA School of Law Lowell Milken Institute for Business Law and Policy sponsored a conference on competing theories of corporate governance.

Corporate law and economics scholarship initially relied mainly on agency cost and nexus of contracts models. In recent years, however, various scholars have built on those foundations to construct three competing models of corporate governance: director primacy, shareholder primacy, and team production.

The shareholder primacy model treats the board of directors as agents of the shareholders charged with maximizing shareholder wealth. Scholars such as Lucian Bebchuk working with this model are generally concerned with issues of managerial accountability to shareholders. In recent years, these scholars have been closely identified with federal reforms designed to empower shareholders.

In Stephen Bainbridge’s director primacy model, the board of directors is not a mere agent of the shareholders, but rather is a sui generis body whose powers are “original and undelegated.” To be sure, the directors are obliged to use their powers towards the end of shareholder wealth maximization, but the decisions as to how that end shall be achieved are vested in the board not the shareholders.

Margaret Blair and Lynn Stout’s team production model resembles Bainbridge’s in that it is board-centric, but differs in that it views directors as mediating hierarchs who possess ultimate control over the firm and who are charged with balancing the claims and interests of the many different groups that bear residual risk and have residual claims on the firm. Although team production is not explicitly normative, many commentators regard it as at least being compatible with stakeholder theorists who promote corporate social responsibility.

This conference provided a venue for distinguished legal scholars to define the competing models, critique them, and explore their implications for various important legal doctrines. In addition to an oral presentation, each conference participant was invited to contribute a very brief essay of up to 750 words (inclusive of footnotes) on their topic to this micro-symposium being published by the UCLA Law Review’s online journal, Discourse.

These essays provide a concise but powerful overview of the current state of corporate governance thinking. Our thanks to all the participants.

An Abridged Case For Director Primacy

Stephen M. Bainbridge

All organizations must have some mechanism for aggregating the preferences of the organization’s constituencies and converting them into collective decisions. As Kenneth Arrow explained in work that provided the foundation on which the director primacy model was constructed, such mechanisms fall out on a spectrum between “consensus” and “authority.”1 Consensus-based structures are designed to allow all of a firm’s stakeholders to participate in decisionmaking. Authority-based decisionmaking structures are characterized by the existence of a central decisionmaker to whom all firm employees ultimately report, and who is empowered to make decisions unilaterally without approval of other firm constituencies. Such structures are best suited for firms whose constituencies face information asymmetries and have differing interests. It is because the corporation demonstrably satisfies those conditions that vesting the power of fiat in a central decisionmaker—such as the board of directors—is the essential characteristic of its governance.

Shareholders have widely divergent interests and distinctly different access to information. To be sure, most shareholders invest in a corporation expecting financial gains, but once uncertainty is introduced shareholder opinions on which course will maximize share value are likely to vary widely. In addition, shareholder investment time horizons vary from short-term speculation to long-term buy-and-hold strategies, which in turn is likely to result in disagreements about corporate strategy. Likewise, shareholders in different tax brackets are likely to disagree about such matters as dividend policy, as are shareholders who disagree about the merits of allowing management to invest the firm’s free cash flow in new projects.

As to Arrow’s information condition, shareholders lack incentives to gather the information necessary to actively participate in decisionmaking. A rational shareholder will expend the effort necessary to make informed decisions only if the expected benefits of doing so outweigh the costs. Given the length and complexity of corporate disclosure documents, the opportunity cost required for making informed decisions is both high and apparent. In contrast, the expected benefits of becoming informed are quite low, as most shareholders’ holdings are too small to have significant effect on a vote’s outcome. Accordingly, corporate shareholders are rationally apathetic.

In sum, it would be surprising if the modern public corporation’s governance arrangements attempted to make use of consensus-based decisionmaking. Given the collective action problems inherent to such a large number of potential decisionmakers, the differing interests of shareholders, and their varying levels of knowledge about the firm, it is “cheaper and more efficient to transmit all the pieces of information once to a central place” and to have the central office “make the collective decision and transmit it rather than retransmit all the information on which the decision is based.”2 Shareholders therefore will prefer to irrevocably delegate decisionmaking authority to some smaller group. As we have seen, that group is the board of directors.

Strong limits on shareholder control are essential if that optimal allocation of decisionmaking authority is to be protected. Any meaningful degree of shareholder control necessarily requires that shareholders review management decisions, and step in when management performance falters to effect a change in policy or personnel. Giving shareholders this power of review differs little from giving them the power to make management decisions in the first place. Even though shareholders probably would not micromanage portfolio corporations, vesting them with the power to review board decisions inevitably shifts some portion of the board’s authority to them. As Arrow explained:

Clearly, a sufficiently strict and continuous organ of [accountability] can easily amount to a denial of authority. If every decision of A is to be reviewed by B, then all we have really is a shift in the locus of authority from A to B and hence no solution to the original problem.3

This remains true even if only major decisions of A are reviewed by B. The separation of ownership and control mandated by U.S. corporate law thus has a strong efficiency justification.

Shareholder vs. Investor Primacy in Federal Corporate Governance

George S. Georgiev

The director primacy model of corporate governance—the notion that boards of directors are not mere agents of shareholders but have broad powers to manage the corporation4—has been widely recognized as the doctrinal lodestar of Delaware corporate law.5 However, the corporate governance reforms contained in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 20026 and the Dodd-Frank Act of 20107 presented a powerful federal intervention into matters that had hitherto been the exclusive domain of state law. These reforms remapped the corporate governance landscape by imposing a series of mandatory rules, which have served to limit Delaware corporate law’s preference for private ordering and constrain the authority of boards of directors.8 As a result, it has seemed logical to interpret recent federal corporate governance reforms as a challenge to the director primacy model9 or as evidence of the ascendance of a shareholder-centric or “shareholder primacy” model of federal corporate governance.10 At its core, the shareholder primacy model contends that “shareholders are the principals on whose behalf corporate governance is organized” and, importantly, that “shareholders do (and should) exercise ultimate control of the corporate enterprise.”11

In this essay, I argue that post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation12 has not followed the shareholder primacy model, because it has not accorded any unique and meaningful governance rights to shareholders as a group. Instead, to the extent that such regulation can be said to favor any particular group, it is investors, not shareholders. In the language of “primacy,” the federal corporate governance regime could thus be described as one of “investor primacy” as opposed to “shareholder primacy.” It is certainly beyond the scope of this short essay to outline a complete theory of federal corporate governance centered around the notion of investor primacy; I am only suggesting that shifting the focus from shareholders to investors can contribute to a more accurate description of post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation. I also argue that the investor-focused regime at the federal level is not necessarily at odds with the director primacy model that dominates Delaware corporate law. My claims are narrow and purely descriptive in nature, and I do not take a normative position on the desirability of enhancing shareholders’ governance rights or the desirability of federal versus state regulation of corporate governance. In addition, I do not dispute that shareholder concerns have become more prominent in recent years or that shareholders are able to exert greater leverage, often informal, over the corporation. I argue only that post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation has not followed the shareholder primacy model, and that, instead, it comports more closely with the investor protection norm embedded in the federal securities laws.

A key to my argument is the distinction between “shareholders” and “investors” and the different mix of functions, powers, and, ultimately, governance rights accorded to these groups by federal law. I use the term “investors” to refer to all capital market participants who view companies as investment prospects, consume company-specific information, and make buying and selling (i.e., trading) decisions about companies’ equity and debt securities based on such information. With respect to any particular company, therefore, shareholders are part of the broad class of “investors,” but this class also includes non-shareholders who have invested in the company’s debt securities, as well as non-shareholders who have not invested in the company’s equity or debt securities but who could do so at any time based on information about the company.

The principle of investor protection has traditionally been a paramount concern of the federal securities laws and has formed the bedrock of the securities disclosure regime established by Congress and the SEC. As used herein, “investor primacy” is about the manifestation of this familiar investor protection norm within the realm of federal corporate governance. Importantly, in its information-producing function, the securities disclosure regime does not make a distinction between shareholders and non-shareholders. Instead, it requires that companies’ disclosure statements are made available to all investors, including debt investors and potential investors, so that they can make informed trading decisions. Because disclosure of material company information has long been the regulatory tool of choice at the federal level, a majority of federal corporate governance rules have been effected through disclosure rules that cater to all investors. Post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation has been no exception: Even where it appears to favor shareholders (e.g., say-on-pay votes), such legislation has not given shareholders additional governance rights or enabled them to exercise control over the corporation, but rather has sought to provide investors with additional and more accurate information for purposes of their trading decisions. The transmission mechanisms can often be unclear, but company disclosure generally affects investor trading decisions, which, in turn, affect the prices of the company’s debt and equity securities. These prices then have the potential to serve as real-time signals affecting the behavior of management teams and boards. In short, investor trading decisions based on disclosure can exert a meaningful influence over company-specific corporate governance.

It has been said that shareholders have three types of rights: to “vote, sell [stock], or sue,” all in limited doses.13 Note that, by contrast and with respect to any specific company, investors as a group have only one of these rights: the right to buy and sell (i.e., trade) the company’s stock and debt securities.14 If the goal of federal corporate governance regulation were to empower shareholders or give them control over the corporation, we might expect that such regulation would seek to expand all three governance rights possessed by shareholders. However, I find that federal corporate governance regulation has sought to affect only the right to trade, which is a right common to both shareholders and investors, by employing various devices to improve the adequacy and accuracy of information flowing from companies to investors and markets. To be sure, federal law has also resorted to non-disclosure based modes of corporate governance regulation (for instance, executive compensation clawbacks in certain circumstances), but those interventions too have failed to grant shareholders any meaningful governance rights beyond the right they already have and share with investors, the right to trade. While a comprehensive survey of federal corporate governance reforms is beyond the scope of this essay, examining a few recent and pending corporate governance initiatives helps illustrate my argument that post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation has not followed the shareholder primacy model.

“Say-on-pay”: On the surface, say-on-pay seems to directly contradict the argument just presented because it ostensibly gives shareholders the right to vote on executive compensation, a matter traditionally reserved for the board. Examined more carefully, however, say-on-pay is not a real “vote” right: The votes are merely advisory, there is nothing to require the board to abide by them, and they do not give shareholders any meaningful control over the corporation. Moreover, the say-on-pay rules do nothing to enhance the second of the two rights unique to shareholders, the right to sue. Courts have considered and rejected the assertion that a negative say-on-pay vote can overcome the business judgment presumption attached to a board’s decision on executive compensation,15 thereby rendering such votes inconsequential with respect to derivative shareholder litigation. As a result, say-on-pay provisions are best viewed as a means of providing investors with additional information about the adequacy of a company’s compensation practices in order to facilitate better trading decisions, and this is fully consistent with the investor primacy framework at the federal level. Say-on-pay does give shareholders some voice, but the growing experience with say-on-pay votes during the past four proxy seasons seems to suggest that shareholders’ message, even when clearly expressed, is rarely heeded.16

Board-Shareholder Engagement: The recent trend in board-shareholder engagement, strongly encouraged by the SEC,17 also appears at first glance to be aimed at empowering shareholders and taking authority away from the board. Upon closer examination, however, board-shareholder engagement does not confer any real powers upon shareholders, and certainly none of the two powers that are unique to them, namely the power to vote and the power to sue. Board-shareholder engagement is best understood as a mechanism for facilitating the exchange of information between the board and shareholders. It fits within an investor primacy framework because it can lead to the consideration by boards of additional inputs and, ultimately, to better disclosure, thereby enabling investors to trade based on more complete information about the company. This information-producing effect is amplified by the structure of SEC Regulation Fair Disclosure: when a company selectively discloses material non-public information to one set of its investors, it is required to disclose the same information to all investors in the market.18 Board-shareholder engagement fits more naturally within an investor primacy model in one additional respect: boards often use such engagement as a means of diffusing confrontations with shareholders and preventing situations in which shareholders may actually have more real power at their disposal (e.g., proxy contests).19

Other Federal Corporate Governance Provisions: The reforms introduced by Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank are fairly easy to square with the investor primacy framework of federal corporate governance. The disclosure-based provisions are aimed at, and result in, greater information flowing to investors,20 but do not give shareholders additional control over the corporation either through voting rights or the right to sue. Other provisions, such as the substantive mandates relating to auditor independence, disclosure controls and procedures, internal controls over financial reporting, and even analyst conflict of interests,21 make structural changes that are aimed at improving the accuracy of the financial information provided to investors in order to facilitate their trading activities. These changes too are more consistent with an investor primacy model than with the shareholder primacy model. To the extent these provisions interfere with boards’ authority, they to do so in favor of investors—by seeking to provide the market with adequate and accurate information in order to trade—and do nothing to empower shareholders by enhancing the two powers that are unique to them, namely the powers to vote and sue.

Disclosure of Positions Held by Activist Shareholders: The anticipated changes to the Schedule 13D waiting period22 are likely to provide further evidence of the investor primacy approach to federal corporate governance regulation. Under the current rules, shareholders can wait ten days before having to file Schedule 13D and notify the market that they have crossed the 5 percent shareholding threshold. This clearly favors activist shareholders, since it allows them to continue accumulating shares without disclosing their intentions to the market or the company for ten days. Shortening or eliminating the waiting period has long been under discussion and, notably, Congress gave the SEC the express authority to adopt rules to this effect as part of Dodd Frank.23 If, as is widely anticipated, the SEC adopts such rules, they would require the disclosure of activists’ trading positions to the market (i.e., all investors) in a timely fashion and would empower both boards and investors vis-à-vis activist shareholders. The new rules would also demonstrate that even in the current environment where vocal calls for the expansion of shareholder rights are made on a regular basis, federal corporate governance regulation still prizes the interests of all investors over those of shareholders alone.

The investor primacy model at the federal level—and the corporate governance regulations just discussed—are not necessarily at odds with the director primacy model, which has been embraced by Delaware state law. It is true that in certain cases federal regulations impinge on board authority, though they do so in largely procedural ways. Ultimately, federal regulations have not taken away any of the real powers of the board and, as argued, have not given any real powers to shareholders. Moreover, in certain cases federal regulations appear to enhance board authority. For example, the SEC’s emphasis on board-shareholder engagement contains an implicit recognition of the board’s primacy over management in intra-company governance since it encourages the partial re-allocation of some of management’s functions (investor relations) to boards of directors under the guise of board-shareholder engagement.

I should underscore that the argument sketched out here—that federal regulation of corporate governance is better described as a model of investor primacy as opposed to shareholder primacy—relates only to the effects of federal regulation. In other words, even though shareholders may have expanded their power and influence in corporate governance in recent years, this has not been the direct result of federal corporate governance regulation. For example, one of the biggest victories for shareholders in recent years has been the declassification of boards as a result of the work of the Harvard Law School Shareholder Rights Project. Since 2012, and over the course of only three proxy seasons, the Project has established 121 successful engagements, which have led to the elimination of staggered boards in approximately two-thirds of S&P 500 companies that had classified boards at the beginning of 2012.24 Even though this outcome may represent a challenge to the director primacy model, it was not achieved as a result of federal corporate governance regulation but through the work of an independent group and with the acquiescence of the very boards that were being declassified.

Finally, the argument I present here is purely descriptive and limited to federal corporate governance regulation. It is not an attack on the normative foundations of the shareholder primacy model or the director primacy model, each of which has substantial normative appeal.25 I have argued only that with respect to any specific corporation, “shareholders” and “investors” are different, albeit overlapping, groups with different governance rights, and that the effect of post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation has not been to accord any unique and meaningful governance rights to shareholders, either vis-à-vis boards or investors. Instead, post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation has sought to provide all investors (including equity and debt investors as well as non-shareholders) with additional information so that they can exercise the only governance right common to all of them, namely the right to trade in a company’s debt and equity securities, on the basis of adequate and accurate information.

Team Production Theory: A Critical Appreciation

David Millon

Margaret Blair and Lynn Stout’s path-breaking Team Production article26 is one of the most important corporate law articles of the past twenty-five years. Drawing on economic theory, Blair and Stout argue that the board’s role is to act as a “mediating hierarch,” balancing the interests of the corporation’s various stakeholders.27 By holding out the promise of better distributional outcomes for nonshareholders, this conception of the board’s role encourages efficiency-enhancing cooperation and willingness to make firm-specific investments.

In an article critical of Blair and Stout’s theory, I took issue with their claim that corporate law reflects a commitment to the team production model (TPM) of corporate governance rather than to shareholder primacy.28 I now think the question is more complex. Blair and Stout’s view that corporate law does not endorse a principal-agent theory of the relation between shareholders and corporate management is correct. They are wrong, however, to the extent that corporate law does embrace a quite different notion of shareholder primacy, one that confers special status on shareholders within the legal structure of corporate governance. I term this the traditional model of shareholder primacy, in contrast to the radical conception that insists on the principal-agent relation.29

Important features of corporate law’s traditional governance structure reflect shareholders’ special status in relation to the corporation’s other stakeholders, although in practice shareholders' governance powers are of limited significance. Ordinarily, shareholders alone enjoy voting rights, information rights, and the right to bring derivative suits. Fiduciary duties are owed to “the corporation and its shareholders.”30 Importantly, however, the traditional model of shareholder primacy does not demand that the board maximize shareholder wealth; it simply insists that the board not disregard shareholder interests for the sake of nonshareholder considerations. And, of equal importance, shareholder control powers under the traditional model “are so weak that they scarcely qualify as part of corporate governance.”31 In other words, traditional shareholder primacy readily accommodates the board discretion that is at the heart of TPM.

Of greater concern is the question whether boards actually function as TPM says they should. The theory depends on the board’s independence and neutrality with respect to potentially conflicting claims of shareholders and nonshareholders. While corporate law certainly confers broad discretion on the board to act as a “mediating hierarch,” it does not mandate that it do so.[32] Blair and Stout are vague about how directors actually make choices, stating that it is a matter of the corporation’s internal politics.32 Extra-legal pressures brought to bear on the board by competing stakeholder groups, not legal rules, will therefore shape the board’s decisionmaking.

In today’s business environment, the boards of most companies tilt decidedly in the direction of their shareholders. Typically this means a strong preference for short-term share price maximization, which is generally a function of quarter-to-quarter accounting results, because this is what most institutional shareholders want. Pressure from these shareholders translates into boards’ reluctance to spend money that will generate returns only in future accounting periods because of the immediate negative impact on the quarterly income statement. That can mean lower expenditures on activities like R&D, marketing, maintenance, and capital investment. It also means unwillingness to invest in nonshareholder well-being with an eye toward long-run financial benefits. Lower-level employees are likely to receive no more than the minimum wage necessary to prevent defection. That shareholders are winning these internal political contests is evident in the fact that corporate stock has returned over 650 percent during the past quarter century, while real wages have stagnated despite significant productivity gains.

Institutional shareholder pressure for short-term share price maximization results from legal obligations or market incentives. Pension funds must write checks each month to their beneficiaries. Mutual funds typically earn their fees based on total assets under management and compete for investor dollars based on quarterly and annual performance.33

Shareholders seeking short-term returns exert pressure in various ways. Large-scale sell-offs due to failure to meet quarterly earnings targets can mean lower share prices leading to reduced CEO compensation or even termination.34 Widespread reliance on proxy advisory firms facilitates coordinated voting.35 Executive compensation incentives also encourage focus on short-term share price,36 as do reputational considerations.37 Social norms nurtured in business schools38 and the business press39 point in the same direction.

Thus, the problem with TPM—a serious one—is that directors don't behave the way the theory says they should. Because corporate law can accommodate either short-term share price maximization or mediation among conflicting shareholder and nonshareholder interests, legal reform is necessary. An ex ante specification of how boards should make trade-off choices is not technologically feasible. Instead, legal reform at the board level could alter executive compensation practices and insulate directors from electoral pressures by providing for longer terms. At the shareholder level, tax policy could be used to discourage short-term investing. Compelling as it is both descriptively, as an explanation for corporate law’s conferral of broad discretion on the board, and normatively, as a directive for how boards should behave, TPM cannot realize its potential in the current business and legal environment.

David and Director Primacy

Usha Rodrigues

Stephen Bainbridge has had at least five articles to develop his director primacy theory.40 I have 750 words to critique it. The odds seem slightly in his favor. But I’m game. I’ll be the David to his Goliath.

I take Bainbridge on his own terms. One hallmark of director primacy is that it describes the structure of corporate law. The proof of the pudding is how it plays out in areas such as the business judgment rule (very well), or takeovers (pretty well). Now for my opening salvo: How well does director primacy fit with two notable developments in corporate law?

First, recently merger lawsuits have exploded; plaintiffs now file suit in 94 percent of public company cases and all have settled.41 Professor Bainbridge cites the derivative suit as proof of the law’s recognition of the board’s centrality.42 Does the rise of these direct suits challenge director primacy?

Second, the Delaware Supreme Court embraced the so-called Caremark duty—in Stone ex rel. AmSouth Bancorporation v. Ritter,43 marrying it with good faith. Bainbridge considers the marriage ill-advised, stripping the board of the discretion to forgo compliance systems while at the same time paradoxically allowing it to escape liability if it blithely and blindly fails to register the need for a compliance system in the first place.44 How to square this result with director primacy?

Ah, but Bainbridge has a ready response to such attacks. He will doubtless say that he does not pretend a unified field theory of corporate law, one that is predictive of every small point of doctrine.45

Hmpf.

How next to carry the attack? How about the charge that director primacy does not reflect the real world? Indeed, my own work has argued that the supermajority independent board of the modern public corporation is ill-suited to carry the burden the director primacy model imposes upon it.46 But Bainbridge will counter that managerial power is a “perversion of the statutory ideal,” and demand that reality conform to theory—citing evidence that it already has.47

Stymied again.

So how’s this for a last shot: could there possibly be something that Bainbridge has missed?

No way.

But let me try anyway. One basic feature of the at-will partnership is that you don’t have to be partners with someone against your will. No one can become a partner unless all of the partners consent. And if you grow to dislike your fellow partners, you can force an exit by dissolving. Corporate law default provides the mirror image: free transferability of shares and an inability to control sale. So one (overlooked? Dare I say it?) justification for director primacy may be that shareholders rationally mistrust other shareholders—not just because, as Bainbridge has observed, they differ in time horizon,48 but also because they are subject to change without notice, leaving the unhappy investor joined to strangers and unable to force liquidation. Vesting a fixed governing body with authority is crucial in a world when one cannot control the identity of her fellow shareholders.

This argument may be flawed, but given Professor Bainbridge’s well-thought-out theory, it would appear to have better odds than a direct attack on director primacy.

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Citizens United, Concession Theory and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Stefan J. Padfield

Corporations are some of the most powerful entities in the world.49 The debate over how best to leverage their power for good has been raging for some time. In the early 1930s, Adolf Berle and E. Merrick Dodd famously brought this debate to the Harvard Law Review. Berle argued that corporations should be run for the benefit of shareholders while Dodd argued they should have broader, socially beneficial goals.50 “By the 1950s, Berle was ready to concede that, as a matter of law, ‘[corporate] powers [are] held in trust for the entire community.’”51

But in the 1970s, Milton Friedman pushed back powerfully against the notion of corporate duties extending beyond shareholder wealth maximization when he wrote: “Few trends could so thoroughly undermine the very foundations of our free society as the acceptance by corporate officials of a social responsibility other than to make as much money for their stockholders as possible. This is a fundamentally subversive doctrine.”52 And so the debate continues to this day.

David Yosifon has entered this debate by arguing that post-Citizens United, corporate social responsibility (CSR) must be mandated. This is because Citizens United undermined one of the key justifications for preserving private ordering. Specifically, prior to Citizens United it had been argued that despite obvious incentives for corporations to externalize costs via regulatory capture, the “regulation of corporate political activity [would] insulate the political process from corporate influence.”53 But in Citizens United the United States Supreme Court took the reins off corporate political activity by holding that corporate political speech could not be regulated on the basis of corporate status alone,54 and thus this justification is no longer effective. Yosifon has also argued that the failure of advocates of CSR to make meaningful progress, even when given such glaring opportunities to challenge the status quo as the relatively recent enactments of Dodd-Frank[56] and Sarbanes-Oxley,[57] stems at least in part from the lack of a compelling narrative.55 It is to these advocates of mandatory CSR that I primarily address my brief comments here.

Theories of corporate governance tend to be focused on the inner workings of corporations and seek to explain who is or should be in charge of corporate decisionmaking, as well as to what end that decisionmaking should be directed. Corporate personality theory, meanwhile, typically seeks to define the nature of corporations vis-à-vis external regulators in a way that will help identify the proper rights and responsibilities of corporations under, for example, the U.S. Constitution. The reader should require only a brief moment of reflection to realize that the lines between internal and external governance quickly become blurred, and thus theories of corporate governance and theories of corporate personality are to at least some meaningful extent interchangeable.56

The three primary modern theories of corporate governance are director primacy, shareholder primacy, and team production theory.57 The three primary corporate personality theories are concession theory, aggregate theory, and real entity theory.58 In my forthcoming essay, Corporate Social Responsibility & Concession Theory, I argue that only concession theory supports mandatory CSR as a normative matter.59

In extremely truncated form, my argument proceeds as follows. While both director primacy and shareholder primacy differ in terms of who should control corporate decisionmaking, both identify shareholder wealth maximization as the positive and normative goal of corporate governance. In addition, while team production theory tempts advocates of CSR, in the end it also falls short of supporting mandatory CSR.60 As for the theories of corporate personality, both aggregate theory and real entity theory view the corporate entity as standing in the shoes of natural persons to some meaningful degree (typically the shareholders in the case of aggregate theory and the board of directors in the case of real entity theory), thereby providing corporations a basis for resisting government regulation. Only concession theory, which views the corporation as fundamentally a creature of the state created to serve public ends, can support mandatory CSR as a normative matter.61 Thus, the advocates of mandatory CSR should use concession theory, with its emphasis on the public roots of corporations, to provide the compelling narrative necessary to move our corporate law beyond its exclusive focus on shareholder wealth maximization.62

Corporate Governance Theory and Review of Board Decisions

Christopher M. Bruner

Prevailing theories of corporate governance advance strikingly different claims regarding the desirable balance of power within, and underlying purpose of, the enterprise. Accordingly, they prompt strikingly different predictions regarding how, and subject to what standards, shareholders may challenge board decisions.

Shareholder Primacy favors strong shareholder powers and exclusive focus on their interests.63 This conception leads one to predict ample opportunity not merely to second-guess board decisions procedurally but to interfere with them substantively.

Director Primacy agrees that generating shareholder wealth is paramount but favors the efficiency of board-centric governance.64 This conception leads one to predict no opportunity for shareholder interference with substantive board decisions, but perhaps limited opportunity to second-guess them procedurally, with restrained judicial review distinguishing the latter from the former.

Team Production resembles Director Primacy in favoring board-centric governance but predicates this on a different conception of corporate purpose, styling the board as a “mediating hierarch” charged with coordinating various constituencies’ contributions to production. This role requires subordination of each constituency’s interests to a broader duty owed to the enterprise.65 This conception naturally leads one to predict sharply constrained opportunity for shareholders to challenge board decisions and a correlatively skeptical judicial posture in the face of such efforts.

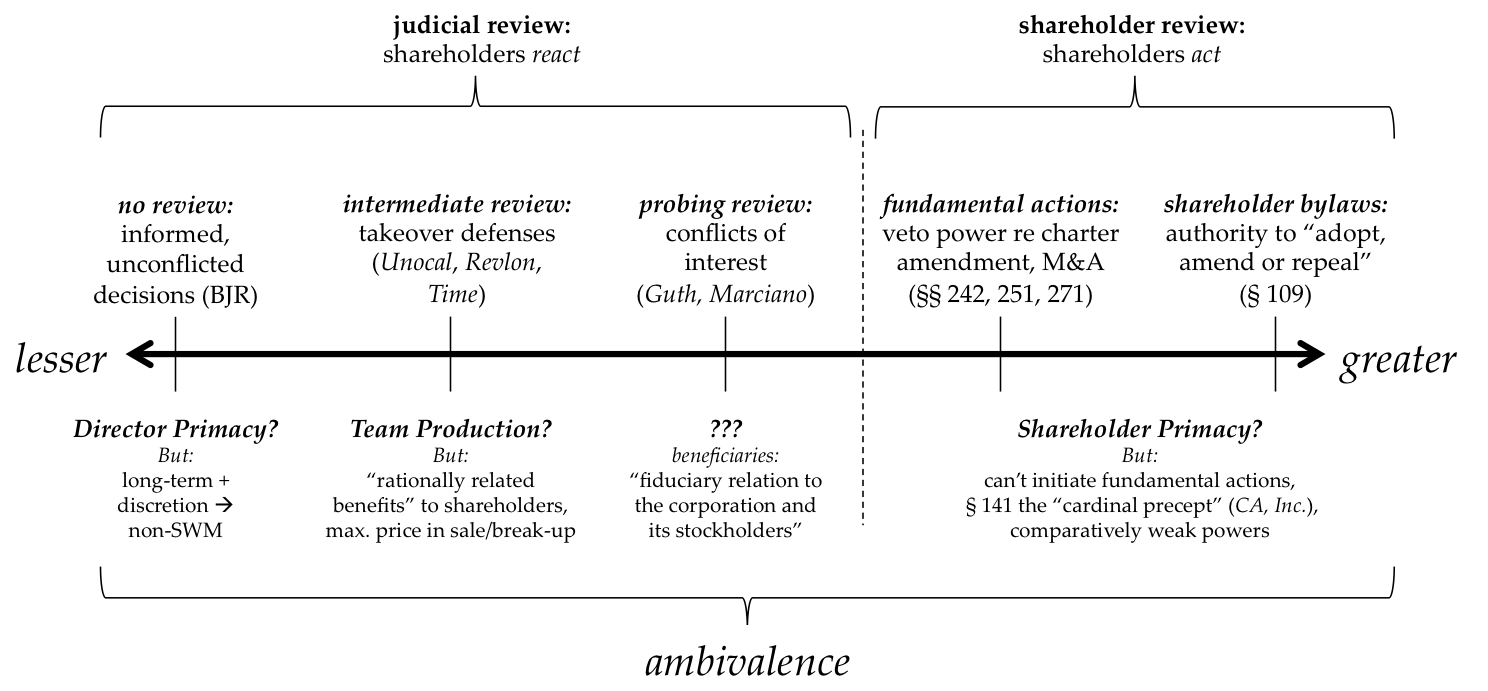

How do these theories and predictions fare descriptively? The figure below arrays illustrative forms of review under Delaware corporate law from lesser to greater intensity. These range from preclusion of substantive review under the business judgment rule; to intermediate review of takeover defenses, involving a proportionality inquiry permitting target boards to consider nonshareholder interests as long as rationally related shareholder benefits can be identified; to probing review of conflicts, requiring directors to establish the transaction’s fairness; to limited forms of self-help, permitting shareholders to respond directly to disagreeable board conduct without resort to courts. The latter category includes veto power over board-proposed fundamental actions and authority to adopt, amend or repeal bylaws—raising the theoretical possibility of repealing board-adopted bylaws or otherwise constraining board power.

Figure 1. Intensity of Review (Delaware) and Theoretical Implications

On balance, none of the foregoing theories provides a compelling descriptive account.66

Director Primacy favors board discretion yet struggles with the board’s practical capacity to deviate from shareholder interests and the shareholders’ capacity for autonomous action.

Team Production favors the combination of strong board powers with express regard for nonshareholders in takeovers. Yet, discretion to consider nonshareholders falls well short of the stakeholder mandate that a true mediating hierarch requires. The shareholders’ capacity to discipline the board through autonomous action further contradicts the team production account.

Shareholder Primacy encounters challenges across the spectrum. Substantial board discretion plainly contradicts the shareholder-centric ideals of power and purpose alike, and the shareholders’ capacity for autonomous action—though real—remains sharply circumscribed. Shareholders may veto fundamental actions but cannot initiate them, and emerging case law suggests that board governance authority trumps the shareholders’ bylaw authority when the two substantively conflict.

Ultimately, there is no clear winner—a reality crystalized in Delaware’s ambiguous formulation of fiduciary duty, owed “to the corporation and its stockholders” simultaneously.67 This formulation remains the great Rohrschach of our field—whatever one wants to think about corporate purpose can be found here.

The normative question is whether strict adherence to any pure theory would prove beneficial. I think not. The social and economic roles of the public corporation are so diverse and far-reaching that we cannot expect any singular conception to serve us well in all contexts. Delaware corporate law’s ambivalence regarding power and purpose reflects the need for flexibility to tailor our working theory of the corporation—and the standards by which board decisions are judged—to varying circumstances.

If any single criterion can explain what we observe, it is sustainability—even if judges rarely acknowledge it. Corporate law is in the business of sustaining business and that criterion will ultimately trump any single constituency’s claims to primacy or decisionmaking authority—no matter how theoretically compelling those claims may otherwise seem.

The Board Veto and Efficient Takeovers

Robert T. Miller

Perhaps the sharpest disagreement between the advocates of shareholder primacy and those of director primacy concerns whether directors should be able to veto a takeover proposal that the shareholders want to accept. In its starkest form, the issue is whether, as in Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. v. Airgas, Inc.,68 a board faced with an all-shares, all-cash, noncoercive tender offer may refuse to redeem a poison pill solely because the directors believe in good faith that the price offered is inadequate.

The arguments turn on contested issues of incentives and knowledge. Both sides agree that, although directors may have incentives to perpetuate themselves in office, shareholders have strong incentives to maximize value for themselves. Both sides also agree that directors have superior information about the value of the company. Shareholder primacy advocates emphasize the superior incentives of the shareholders and downplay the superiority of the directors’ knowledge, arguing that the directors can disclose to the shareholders whatever superior information they have. Director primacy advocates emphasize the superior knowledge of the directors and downplay the possibility of directorial self-interest, arguing that independent directors will generally act to maximize shareholder value. Moreover, both sides agree that maximizing shareholder value should be the goal, for in this context shareholder value is a reliable proxy for social welfare.69

I want to make two points about these arguments, both of which favor director primacy. First, it’s quite absurd to think that the board can convey to the shareholders all the relevant information it possesses. When a friendly acquirer conducts due diligence on a target, the acquirer has teams of businesspeople, bankers, lawyers, accountants, and other experts evaluate terabytes of information about the target, supplementing such studies with in-person conversations with the target’s personnel and on-site inspections of its facilities. The information a target board discloses to its shareholder is nothing like this. For example, during the prolonged Air Product matter, Airgas was implementing a new software platform that it claimed would increase its operating income by between $75 and $125 million per year.70 The financial advisor engaged by the Air Products nominees elected to the Airgas board testified that the implementation plan was “the most detailed plan he and his team had come across in 25-30 years.”71 But the Airgas shareholders never saw the intricate details of the plan. They got a seven page description of the plan that headlined the $75 to $125 million in added operating income but never explained how those figures were computed. Disclosing such critical but highly-detailed information is hopelessly impracticable. Even leaving aside problems concerning competitively sensitive information and potential liability under the securities laws, the vast majority of shareholders would not have a sufficiently large financial stake in the company to make analyzing the information worthwhile. Hence, in most instances, the shareholders’ information deficit will be substantial and irremediable.

Second, if they are even slightly risk averse, shareholders will have strong incentives to sell their shares too cheaply, thus producing socially suboptimal results. The reason is that, because of their information deficit, the decision shareholders make is very different from the decision directors make. Conscientious directors will value the company’s shares, generally in a discounted cash flow study employing the market rate equity cost of capital for the business. Such a study will produce a range of values. Suppose, as was approximately the case in Air Products v. Airgas, the board values the company between $70 and $86 per share and then announces that it will not sell for less than $78 per share.72 The acquirer refuses to raise its offer above $70 per share. Because of their informational deficit, the shareholders cannot value the company themselves but merely form an opinion as to whether they believe the board’s valuation is correct. Assume that a shareholder thinks there is a 55 percent chance that the board is right and the shares are worth $78, a 25 percent chance the shares are worth $70, and a 20 percent chance the shares are worth only $60, the undisturbed market price. This implies an expected value of $72.40 per share. Will a shareholder tender at $70? If he is even slightly risk averse, he will. And this is true even though the shareholder thinks the expected value of the shares is greater than the deal price and even though the shareholder thinks it is more likely than not that the board’s valuation is correct. Shareholder incentives skew towards accepting suboptimal offers.

Toward a Theory of Shareholder Leverage

Lisa M. Fairfax

Over the past several years increased shareholder activism has triggered significant corporate governance changes aimed at enhancing shareholders’ power over director elections and corporate affairs. These changes threaten both the director primacy theory and the team production theory of corporate governance by undermining directors’ broad discretion to make decisions on behalf of the corporation and all of its constituents. But such changes have not resulted in a regime of shareholder primacy. Rather they can be better understood as a regime of shareholder leverage. Despite the increased power at their disposal, in most circumstances, the shareholders remain content to defer to directors. When they are not content, directors retain the freedom to ignore and even circumvent shareholders’ will, blunting the force of increased shareholder power. The theory of shareholder leverage therefore contends that while the current governance regime paves the way for shareholders to exercise greater influence over director decision-making, directors still appropriately remain the primary power source in the modern public corporation.

A significant number of corporate governance changes have occurred in the past few years, particularly surrounding executive compensation and director elections. Indeed, public company shareholders now have a say on pay—an advisory vote on the compensation packages of the top executives.73 Additionally, director election processes have been radically altered. By the beginning of 2014, 91 percent of S&P 500 companies had declassified their boards—up from 40 percent a decade ago74—and almost 90 percent of S&P 500 companies had adopted some form of majority voting whereby directors must either receive a majority shareholder vote or resign upon failure to receive majority shareholder support.75 In 2006, only 16 percent of S&P 500 companies had implemented such standards.76 Moreover, while the D.C. Circuit overturned the Security and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) mandated proxy access rule which would have required that corporations enable certain shareholders to nominate candidates of their choice on the corporation’s proxy statement,77 beginning in 2012 shareholders have been allowed to submit shareholder proposals seeking to adopt procedures for proxy access.78 These changes collectively pave the way towards greater shareholder influence over corporate affairs.

Such changes also appear to breathe new life into the shareholder primacy theory while undermining both the director primacy and team production theory of corporate governance. Enhanced shareholder power certainly runs counter to the broad director discretion envisioned by director primacy. It not only limits director decision-making in connection with management and their pay policies but also constrains directors’ freedom to make business decisions that may be disfavored by shareholders. Increased shareholder power also increases the probability that directors will focus exclusively on shareholders rather than balancing the competing concerns of all corporate constituents as envisioned by the team production model.

But evidence reveals that with respect to compensation and election matters, shareholders are largely content not to exercise their increased powers. Thus, the vast majority of directors continue to get elected at high rates.79 In the last election cycle, only 61 director nominees received less than majority support.80 Similarly, shareholders overwhelmingly approve the vast majority of pay packages, with the result that less than 2 percent of company pay packages get rejected.81 Then too, when shareholders exercise their power, directors are able to thwart that exercise. There are several highly publicized examples of shareholders repeatedly rejecting pay packages that corporations do not alter.82 This is because some corporations have opted to ignore the advisory say on pay vote. Evidence also reveals that most directors who fail to receive a majority of the shareholder vote remain on the board. Of the 61 directors who failed to receive majority vote in 2013, 51 remained on the board at the start of the 2014 proxy season, resulting in what some have called “zombie directors.”83 This is because the board has discretion to refuse to accept directors’ resignations or otherwise retain directors, when they fail to get a majority vote.84 This means that directors have considerable discretion to make decisions that are at odds with shareholder preferences.

To be sure, despite this discretion shareholders do enjoy significantly more sway over director decision-making. Empirical evidence confirms that directors have increased their engagement with shareholders, enhanced their disclosures in an effort to prevent any shareholder discontent, and altered their policies on compensation as well as director recruitment and retention.85 These actions suggest that while the board continues to have considerable discretion in the current corporate governance regime, shareholders have increased leverage. The critical question then becomes whether a shareholder leverage model of corporate governance can provide a more appropriate balance between board discretion and accountability.

Shadow Directors

Iman Anabtawi

United States corporate law is not well-suited to dealing with active shareholders. On the contrary, the presumption that shareholders of public companies do not exert meaningful influence over managerial decisions is thoroughly embedded in U.S. corporate law. Consistent with this presumption, the law does not typically regulate the exercise of shareholder power. Outside of very limited circumstances—namely, instances in which shareholders control a company’s board of directors—shareholders are free to engage with the company in furtherance of their self-interest. It is the duty of the board, and only the board, to mediate among the sometimes conflicting preferences of a company’s constituencies, including its various shareholders, in making managerial decisions.

Changes in both shareholder composition and shareholder rights have dramatically increased the power of shareholders in recent years. As a result, separation of ownership and control no longer fully describes corporate governance in U.S. public companies. Active shareholders are now relevant actors with respect to both corporate policies and business decisions. Yet, these shareholders operate in the shadow of formal directors, sheltered from fiduciary duties, which directors owe to all shareholders. Now that the traditional boundaries between the roles of directors and shareholders are becoming less clear, the obvious question to ask is, “How should the law hold shareholders accountable when they actively engage with issuers?”

Professor Stephen Bainbridge is rightly concerned that shareholder activism undermines the notion of board primacy in corporate governance.86 He suggests that in order to preserve managerial decisionmaking in the board, a distinction should be made between shareholder interventions directed at substantive decisions, which should be discouraged, and those directed at procedural interventions, which facilitate the exercise of the traditional rights of shareholders.87 If one’s aim is to respect the classic roles of boards and shareholders, distinguishing between shareholder interventions on the basis of substance and process makes sense. Some procedural interventions, however, may be motivated by private rent-seeking and some substantive interventions may not. Moreover, it is not always possible to distinguish between the two types of interventions. Finally, recent gains by shareholders with respect to substantive interventions are likely to be difficult to roll back.

Another approach, advanced by Professor Michelle Harner, would defend board primacy against muscular shareholders by strengthening the board’s accountability to all shareholders in circumstances where the board makes a decision on a matter that exclusively benefits one or more shareholders to the detriment of the corporation or its other shareholders.88 Harner’s proposal would essentially impute to the board the self-dealing of the favored shareholders. As a result, the board would bear the burden of showing that the applicable transaction meets the entire fairness standard.89

Harner’s proposal for addressing rent-seeking by activist shareholders is consistent with director primacy in that it acknowledges that the board is the central manager of the corporation. On the other hand, it eviscerates the business judgment rule and consequently reduces board discretion whenever the board’s actions meet the shareholder benefit/detriment test. A departure from the business judgment rule in circumstances where the board itself is not conflicted would foster the very sort of litigation against which corporate law is designed to protect directors.

Professor Lynn Stout and I have advanced an alternative basis for separating shareholder interventions that are value-enhancing from those that represent private rent-seeking—extending fiduciary duties to shareholders who exercise de facto control over a corporate decision.90 In the U.S., activist shareholders are currently allowed to have it both ways: Like directors, they can influence managerial decisions, but unlike directors, they do not typically have fiduciary duties. Already, the law extends fiduciary duties to a shareholder who dominates the board.91 The law should go further and encourage a shareholder who chooses to be active to exert its efforts on behalf of all shareholders rather than allow it to function as a shadow director who occupies a fiduciary-duty-free zone.

Shareholder Primacy and the Misguided Call for Mandatory Political Spending Disclosure by Public Companies

Michael D. Guttentag

Some might claim shareholder primacy has significant implications for the types of information public companies should be required to disclose. Such an argument would observe that ready access to information about firm activities is a prerequisite for shareholders to exercise their legitimate rights as the firm’s owners. Lucian Bebchuk and Robert Jackson’s proposal that public companies be required to disclose information about political spending offers an example of how a link might be drawn between shareholder primacy and mandatory disclosure.92 Bebchuk and Jackson offer a number of arguments as to why public companies should be required to disclose political spending, but the genesis of their proposal appears to be that such disclosure is a prerequisite for shareholders to exercise their ownership rights.93

This brief Essay takes issue with efforts to draw a connection between shareholder primacy and mandatory disclosure requirements and offers the Bebchuk and Jackson political spending disclosure recommendation as an example of the shortcomings of such an approach. Linking shareholder primacy to mandatory disclosure proposals fails to give appropriate weight to either the ways in which private ordering can be relied upon to determine the information firms disclose or the likely costs of imposing unnecessary mandatory disclosure requirements on all public companies.

The analysis of whether to mandate the disclosure of certain categories of information should start with the scholarship on public company disclosure regulation generally and market failure arguments for mandatory disclosure regulation in particular. Approaching the question of mandatory disclosure of political spending in this manner leads to a different and more reliable result.

The scholarly debate on public company disclosure regulation identifies only two market failures that are sufficiently large to justify regulatory intervention. These two market failures are caused by: 1) positive externalities, and 2) insider tunneling of firm assets. Neither of these market failures can fully justify making the disclosure of political spending mandatory.

The positive externalities justification for disclosure regulation is based on the premise that public companies systematically underdisclose. Companies underdisclose because of difficulties they face in capturing the benefits their disclosures provide to: 1) competitors, 2) other firms with publicly-traded securities, or 3) the economy at large.94 But less information does not, per se, make investors worse off. A justification for regulatory intervention based on the goal of adjusting for positive externalities must also show that the underdisclosure caused by positive externalities has generated social costs that regulatory intervention can successfully ameliorate.

Political spending information is unlikely to be withheld because of positive externalities, and, even if it were, its nondisclosure is unlikely to impose social costs. The better explanation for nondisclosure of political spending information by many firms is that the amounts involved are trivially small.95 One additional issue that needs to be addressed before entirely dismissing positive externalities as a justification for mandating political spending disclosure is evidence that political spending information provides a small, but statistically significant, amount of information about the future performance of a firm’s securities.96 Some might argue that the nondisclosure of information despite its value in pricing a firm’s shares is evidence of a positive externality market failure. But political spending is not actually the cause of the measurable decline in firm value that it foretells. Rather, these expenditures provide an informative signal about otherwise unobservable firm attributes that are the actual cause of a decline in future firm value. Mandating the disclosure of an informative signal is not likely to benefit shareholders even in the event that the signal is withheld because of positive externalities.

Underdisclosure by firm insiders to facilitate tunneling (the extraction of value from the firm for personal benefit by those who manage or control the firm) is the second market failure that can provide an economic justification for public company disclosure regulation.97 There are several indications that political spending constitutes a form of tunneling by firm insiders. For example, higher levels of political spending are observed at firms where the amount of tunneling overall is higher, and there is a correlation between the political beliefs supported by the firm and those held by the firm’s CEO.98 But these correlations are not as suggestive that political spending constitutes tunneling as it might seem, and the more important question is whether there is evidence that mandating disclosure of political spending would provide a cost-effective means to deter tunneling. The answer to this more relevant question is no.99

Moreover, imposing even seemingly minimal additional disclosure requirements on public firms based on unsubstantiated claims of potential benefits is problematic for three reasons. First, for many firms it is now easy and palatable to remain outside of the public company reporting regime, especially with changes enacted as part of the JOBS Act.100 Unnecessary disclosure requirements may simply create a subsidy for firms that choose to avoid or exit the public disclosure regime. Second, the cost of a one-size-fits-all disclosure requirement is likely to increase as differences between the types of firms required to comply with this disclosure requirement increase. Firms with an obligation to comply with public disclosure obligations are a strikingly heterogeneous group. Third, any disclosure obligation once imposed is likely to remain in place for no other reason than administrative inertia. Ideally, it would be feasible to experiment with the introduction of new disclosure obligations and then have the ability to remove them, if the resulting evidence showed that the costs of the disclosure obligation exceeded the benefits. But our disclosure system is not yet that easily modified.101

Even if one accepts the core tenets of shareholder primacy, focusing on shareholder empowerment to guide selection of the content of mandatory disclosure obligations only distracts from the analysis necessary to develop a coherent, evidence-based public company disclosure regime. At first glance, imposing a political spending disclosure requirement appears reasonable based on shareholder concerns; however, when one looks to more fundamental market failure considerations, the wisdom of imposing such a requirement is not supported by the available evidence.

Averages or Anecdotes? Assessing Recent Evidence on Hedge Fund Activism

James J. Park

A common criticism of shareholder activism is that it forces companies to focus on short-term results at the expense of long-term performance. For example, in 2013, despite its spectacular success, aggressive investors criticized Apple’s capital structure, leading it to distribute capital to shareholders by repurchasing shares rather than reinvest those funds to develop new products. Such anecdotes have spurred cries for reform.102 A recent study by Professors Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alon Brav, & Wei Jiang (the Hedge Fund Study) counters these anecdotes with analysis of data on around two thousand instances of hedge fund activism spanning the period from 1994 to 2007.103 The Hedge Fund Study shows that on average, such activism does not harm the targeted company. This short symposium piece contrasts these two approaches—anecdotes and averages—in assessing hedge fund activism.

In its most extensive analysis, the Hedge Fund Study relies on a broad definition of activism. The data set consists of “2,040 Schedule 13D filings by activist hedge funds during the period 1994-2007.”104 The initial analysis of this study thus includes any situation where a hedge fund acquires a 5 percent stake in a public corporation, regardless of whether it intends to push for significant change. With respect to this broad view of activism, the study shows that there is no evidence of significant declines in operating performance or stock returns relative to other industry firms for a five-year period after the hedge fund discloses its stake in the company.105

In a response to the Hedge Fund Study, a memo by the prominent law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz disputed whether any “empirical study . . . is capable of measuring the damage done to American companies and the American economy by the short-term focus that dominates both investment strategy and business-management strategy today.”106 Among other arguments, the memo contends that the study “rejects and denies . . . anecdotal evidence” in coming to its conclusions.107

While it cannot answer whether a “short-term” mentality is generally problematic, the Hedge Fund Study is evidence that, on average, hedge fund activism (broadly defined) is not causing measurable harm to the performance of public corporations. The advantage of the study’s approach is that it systematically analyzes data on virtually all instances of activism over the years rather than focusing on a handful of experiences. On the other hand, because the initial analysis covers any investment of 5 percent or more in a company, its broadest results do not eliminate the possibility that particular types of activism can be problematic.

Indeed, the Hedge Fund Study spends much less time analyzing narrower categories of hedge fund activism. It found similar results for smaller subsets of the data, such as interventions involving “adversarial” activism, which includes any 13D filing that “threatens or opens the door to a proxy contest, a lawsuit, or public campaigns involving confrontation.”108 These “adversarial” interventions cover “21.6% of the universe of all interventions” in the data set.109

Even this narrower category of “adversarial” activism is too broad to permit firm conclusions. Not all “adversarial interventions” are alike. There is a significant difference between a threat of a proxy contest and an actual proxy contest. An intervention leading to an actual proxy contest is far more serious and likely to result in actual changes in the company’s strategy. A powerful anecdote on the dangers of activism resulting in substantial company change is the damaging intervention suffered by J.C. Penney. An activist fund acquired a substantial stake in the company, obtained a seat on the board, and pushed for a new CEO, who then implemented a strategy that drove the company to the brink of bankruptcy. The Hedge Fund study would lump the J.C. Penney example with cases where activists did no more than “threaten” a proxy contest. The performance of the companies that received no more than an idle “threat” might obscure the results of companies that were subject to more invasive activism.

Perhaps a study of a smaller subset of hostile interventions, such as cases where an activist investor was successful in obtaining a board seat, might provide more persuasive evidence. The difficulty with studying such smaller groups is that there might be insufficient examples to draw clear conclusions. If that is the case, empirical analysis may not do much to resolve the debate on hedge fund activism.

Finally, it is important to recognize that these results are from a world where activism is often blocked by the law’s support of director primacy. Proxy contests are expensive and difficult, poison pills block hostile takeovers, and Delaware law provides significant protection for directors exercising their business judgment.110 Perhaps hedge fund activism does not cause much harm because the law is stacked against shareholders in terms of their ability to effectuate meaningful change in most instances. The Hedge Fund Study says little about a world where the law significantly empowers shareholders. Anecdotes such as the case of J.C. Penney might actually say as much as averages in assessing hedge fund activism.

- Kenneth J. Arrow, The Limits of Organization 68–69 (1974). ↩

- Id. at 68. ↩

- Id. at 78. ↩

- See Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy, in Research Handbook on the Economics of Corporate Law (2012). ↩

- See, e.g., In re CNX Gas Corp. S’holders Litig., 4 A.3d 397, 415 (Del. Ch. 2010) (stating that “director primacy remains the centerpiece of Delaware law, even when a controlling stockholder is present”). ↩

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745 (2002). ↩

- Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010). ↩

- See, e.g., Roberta Romano, The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the Making of Quack Corporate Governance, 114 Yale L.J. 1521 (2005); Stephen M. Bainbridge, Dodd-Frank: Quack Federal Corporate Governance Round II, 95 Minn. L. Rev. 1781 (2011). ↩

- Holly J. Gregory & Rebecca C. Grapsas, In the Interests of Avoiding Further Federal “Quackery,” 91 Tex. L. Rev. 889, 890–91 (2013) (reviewing Stephen M. Bainbridge, Corporate Governance After the Financial Crisis (2012)) (arguing that “the corporate governance provisions of Dodd-Frank veer sharply away from director primacy”). ↩

- See, e.g., Lisa M. Fairfax, Mandating Board-Shareholder Engagement?, 2013 U. Ill. L. Rev. 821, 825–830 (2013) (asserting that in recent years “shareholders have waged an aggressive battle to gain more influence over directors and corporate affairs” and presenting an overview of “shareholder victories”). ↩

- Stephen M. Bainbridge, The New Corporate Governance in Theory and Practice 21 (2008). ↩

- As used herein, “post-crisis federal corporate governance regulation” encompasses the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, SEC rulemaking stemming from these Acts, and SEC policy statements relating to corporate governance, as well as relevant federal court decisions. For this reason, SEC Rule 14a-11 on proxy access, which expressly favored shareholders but was invalidated by the D.C. Circuit Court in Business Roundtable v. SEC, 647 F.3d 1144 (D.C. Cir. 2011), is not inconsistent with my argument. ↩

- Robert B. Thompson, Preemption and Federalism in Corporate Governance: Protecting Shareholder Rights to Vote, Sell, and Sue, 62 Law & Contemp. Probs. 215, 216 (1999). ↩

- Investors can sell a company’s securities even when they do not own them by shorting and, indeed, a great many do so on a regular basis as evidenced by the size of the market for derivatives. ↩

- See Michael C. Holmes & Alithea Z. Sullivan, Say-On-Pay Lawsuits Losing Steam, Law360 (July 10, 2012), http://www.law360.com/articles/355799/say-on-pay-lawsuits-losing-steam. ↩

- Mathias Kronlund & Shastri Sandy, Does Shareholder Scrutiny Affect Executive Compensation? Evidence from Say-on-Pay Voting (Apr. 7, 2014) (unpublished manuscript), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2358696 (empirical study finding that say-on-pay votes “improve the ‘optics’ of pay, and, contrary to the goals of the say-on-pay regulation, result in higher, not lower, total pay”). Consider also the example of Citigroup, which held arguably the most high-profile failed say-on-pay vote to date in 2012, without subsequently reducing the CEO’s compensation. When the CEO was ultimately forced out, it was months after the vote and in the context of a chronically underperforming stock price. See Jessica Silver-Greenberg & Susanne Craig, Citigroup’s Chief Resigns in Surprise Step, N.Y. Times, October 16, 2012 (chronicling the events preceding the CEO’s departure based on insider accounts, and making no mention of the failed say-on-pay vote as a contributing factor). While it is not possible to establish the precise causal links, the fact pattern seems to suggest that the shareholder signal (say-on-pay) was ignored, while the investor signal (stock price) was taken seriously and led to the CEO’s dismissal. ↩

- See Mary Jo White, Remarks at the 10th Annual Transatlantic Corporate Governance Dialogue (Dec. 3, 2013), available at http://www.sec.gov/News/Speech/Detail/Speech/1370540434901 (arguing that “the board of directors is—or ought to be—a central player in shareholder engagement” and noting that “even in companies with so-called state of the art corporate governance practices, engagement with shareholders provides very valuable feedback and insights”). ↩

- The interpretive guidance on Regulation FD issued by the SEC in 2010 does not modify this basic principle. See Regulation FD, U.S. Sec & Exch. Comm’n, http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/guidance/regfd-interp.htm (last updated June 4, 2010). ↩

- See, e.g., How to Avoid a Proxy Contest Through Constructive Engagement, Nat’l Assoc. of Corp. Dirs., http://northerncalifornia.nacdonline.org/Events/EventDetail.cfm?ItemNumber=10286 (last visited June 16, 2014) (National Association of Corporate Directors seminar on “how engaging with shareholders can promote better and more constructive relations between companies and their shareholders [with] benefits . . . such as the potential to avoid proxy contests”). ↩

- E.g., Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111–203, § 953, 972, 124 Stat. 1375 (2010) (additional executive compensation disclosure, and disclosure relating to the split of the positions of CEO and board chair, respectively); Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-204, § 401, 116 Stat. 745 (2002) (disclosure of off-balance sheet items). ↩

- Id. §§ 201, 302, 404, 501. ↩

- See View Rule, Reginfo.gov, http://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=201210&RIN=3235-AK42 (last visited June 16, 2014) (“The Division is considering recommending that the Commission issue a concept release to identify possible revisions to [relevant rules] to modernize the beneficial ownership reporting requirements. The concept release would solicit comment on, among other things, . . . shortening the filing deadlines, and public disclosure of significant short positions and short sales.”). ↩

- See 15 U.S.C. § 78m(d)(1) (2012). ↩

- See Shareholder Rights Project, Harvard Law Sch., http://srp.law.harvard.edu/companies-entering-into-agreements.shtml (last visited June 17, 2014). ↩

- See, respectively, Lucian A. Bebchuk, The Case for Increasing Shareholder Power, 118 Harv. L. Rev. 833 (2005), and Bainbridge, supra note 4. ↩

- Margaret M. Blair & Lynn A. Stout, A Team Production Theory of Corporate Law, 85 Va. L. Rev. 247 (1999). ↩

- Id. at 276–87. ↩

- David Millon, New Game Plan or Business As Usual? A Critique of the Team Production Model of Corporate Law, 86 Va. L. Rev. 1001 (2000). ↩

- I elaborate on the two meanings of shareholder primacy in Radical Shareholder Primacy, U. St. Thomas L.J. (forthcoming 2014). ↩

- Arnold v. Soc’y for Sav. Bancorp, Inc., 678 A.2d 533, 539 (Del. 1996); Loft, Inc. v. Guth, 2 A.2d 225, 238 (Del. Ch. 1938), aff’d sub nom. Guth v. Loft, Inc., 5 A.2d 503 (Del. 1939). ↩

- Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy: The Means and Ends of Corporate Governance, 97 Nw. L. Rev. 547, 569 (2003). ↩

- Id. at 323. ↩

- For further discussion, see David Millon, Shareholder Social Responsibility, 36 Seattle U. L. Rev. 911 (2013). ↩

- See Dirk Jenter & Katharina Lewellen, Performance-Induced CEO Turnover 2–5 (Feb. 2010) (working paper); Steven R. Matsunaga & Chul W. Park, The Effect of Missing a Quarterly Earnings Benchmark on the CEO’s Annual Bonus, 76 Acct. Rev. 313, 330–31 (2001). ↩

- See, e.g., David Gelles, Lively Debate on the Influence of Proxy Advisory Firms, N.Y. Times, Dec. 5, 2013, http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/12/05/lively-debate-on-the-influence-of-proxy-advisory-firms. ↩

- See Andrew C.W. Lund & Gregg D. Polsky, The Diminishing Returns of Incentive Pay in Executive Compensation Contracts, 87 Notre Dame L. Rev. 677, 680 (2011). ↩

- John R. Graham, Campbell R. Harvey & Shiva Rajgopal, The Economic Implications of Corporate Financial Reporting, 40 J. Acct. & Econ. 3, 28 (2005). ↩

- See Rakesh Khurana, From Higher Aims to Hired Hands 317–26 (2007). ↩

- See, e.g., Aneel Karnani, The Case Against Corporate Social Responsibility, Wall St. J. (Aug. 23, 2010), http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748703338004575230112664504890. ↩

- Stephen M. Bainbridge, Response, Director Primacy and Shareholder Disempowerment, 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1735 (2006); Stephen M. Bainbridge, Response, Director Primacy in Corporate Takeovers: Preliminary Reflections, 55 Stan. L. Rev. 791 (2002); Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy: The Means and Ends of Corporate Governance, 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 547 (2003); Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director v. Shareholder Primacy in the Convergence Debate, 16 Transnat’l Law. 45 (2002); Stephen M. Bainbridge, UNOCAL at 20: Director Primacy in Corporate Takeovers, 31 Del. J. Corp. L. 769 (2006). At Professor Bainbridge’s suggestion I will focus largely on the articulation in his “Director Primacy” chapter of the Research Handbook on the Economics of Corporate Law. Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy, in Research Handbook on the Economics of Corporate Law (2012) [herinafter Director Primacy]. ↩

- Liz Hoffman, First Rule of Mergers: To Fight is to Lose, Wall St. J., Mar. 6, 2014, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303949704579457414255774166. ↩

- Director Primacy, supra note 1, at 29. ↩

- 911 A.2d 362, 369–70 (Del. 2006) (en banc). ↩

- Stephen M. Bainbridge et al., The Convergence of Good Faith and Oversight, 55 UCLA L. Rev. 559, 605 (2008). ↩

- Director Primacy, supra note 1, at 28. ↩

- Usha Rodrigues, A Conflict Primacy Model of the Public Board, 2013 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1051, 1083–84 (2013). ↩

- Director Primacy, supra note 1, at 29. ↩

- Id. at 22. ↩

- See generally Vincent Trivett, 25 US Mega Corporations: Where They Rank if They Were Countries, Business Insider (June 27, 2011, 11:27 AM), http://www.businessinsider.com/25-corporations-bigger-tan-countries-2011-6?op=1#ixzz2wpZB2oDn (comparing the revenues of individual, American corporations to the GDP of foreign countries). ↩

- A. A. Berle, Jr., Corporate Powers as Powers in Trust, 44 Harv. L. Rev. 1049 (1931); E. Merrick Dodd, Jr., For Whom Are Corporate Managers Trustees?, 45 Harv. L. Rev. 1145, 1147–48 (1932). ↩

- Margaret M. Blair & Lynn A. Stout, A Team Production Theory of Corporate Law, 85 Va. L. Rev. 247, 303 (1999) (quoting Adolf A. Berle, Jr., The 20th Century Capitalist Revolution 169 (1954)). ↩

- Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom 133 (1962). ↩

- David G. Yosifon, The Public Choice Problem in Corporate Law: Corporate Social Responsibility After Citizens United, 89 N.C. L. Rev. 1197, 1198 (2011); see id. at 1197 (“After Citizens United, we must begin to restructure corporate law to require boards of directors to actively attend to the interests of multiple stakeholders at the level of firm governance.”). ↩